I had the pleasure to interview Eric Markowitz and Dan Crowley of Worm Capital. Here you can find the full interview. Below is the transcript.

- Introduction

- Where do you see Worm Capital in five years?

- A shout out to Stream by Mosaic

- Value vs Growth: How Worm Capital sees it

- Why Arne couldn’t participate in the interview

- What do Dan and Eric do at Worm Capital?

- How to filter noise and signal

- What does Worm Capital’s new approach mean?

- What kind of companies do they like to invest in?

- What role does historical data play for you?

- The top sectors in Worm Capital’s focus

- What gives you confidence?

- Are you shorting in the energy sector? And why are you shorting?

- Why the effort of shorting?

- What are the principles of your company?

- How does your digging work?

- What digging did you do for the big positions in Tesla?

- What else is misunderstood in Tesla?

- Where did you get the idea to invest in Spotify?

- What options could become real businesses at Spotify?

- Why do you prefer Spotify instead of music labels?

- How much self-disruption is embedded in the DNA of Worm Capital?

- Is there something you want to add?

- Disclaimer

Introduction

[00:00:00] Tilman Versch: Hello, Dan and Eric. So great to have you here. You’re my guests from Worm capital, and I’m very interested in getting to know your firm. How are you doing?

[00:00:09] Eric Markowitz: Good Tilman. It’s good to be with you.

[00:00:11] Dan Crowley: Yep. Yep. Doing well. Yeah. Appreciate you having us.

[00:00:15] Tilman Versch: You’re working remotely. Where in the US are you located?

[00:00:17] Eric Markowitz: I’m in Portland, Oregon today.

[00:00:22] Dan Crowley: And I’m in Boulder, Colorado.

Where do you see Worm Capital in five years?

[00:00:25] Tilman Versch: Yeah, I’m here in Stuttgart, in Germany. Down the street is the headquarters of Daimler, which is one of the competitors of Tesla. And we will go into Tesla a bit later during our interview, but first I want to have a look at your funds. You had a great, quite interesting, and impressive performance with two of your funds. It was 37% and 57% since inception of the funds. Really impressive. I want to start with the question where do you see yourself? Not only in terms of performance, but also, involvement of the firm, because this is an impressive track record and it’s hard to keep it up, but how do you see yourself in five years?

[00:01:10] Eric Markowitz: Yeah, sure. Maybe I’ll take a stab at that first. It’s a pretty open-ended question and Dan can correct me where I’m wrong or have his own thoughts. But frankly, we don’t try to focus too much on the year-over-year performance or certainly not monthly or quarterly. We’re just trying to get into position for what we view as a pretty chaotic next ten years of investing.

In our particular strategies, we look for industries that are undergoing significant changes due to a new technological innovation. And so, for us, this is a great time to be stock pickers. We see a lot of misinformation. We see a lot of chaos. Within that chaos, we find a lot of opportunity. So, probably won’t comment too much specifically on performance-wise. We just think that there is abundant opportunity right now but there’s also a lot of risks and challenges embedded in this market, given sort of the velocity of change that we’re seeing on the ground level of the businesses that we study. Businesses that maybe were once considered safe are no longer in our perspective, that safe of an investment, if they cannot make transition to a new type of paradigm of a technology that’s being adopted. So, on a high level, we’re just super excited about the next 10 years. We think there’s a ton of opportunity. We don’t do toomuch sort of public-facing marketing. A lot of our clients have been with us for a long time, but we’re obviously speaking with you today, we’re open to learning from and working with new investors. And so, we’re excited to have that opportunity as well.

[00:02:47] Dan Crowley: Yeah. And I might just tack on, totally agree with what Eric said is that the foundation of the strategy which we launched in 2012 was to capitalize on these really dramatic changes that we foresaw in the market. And from our perspective, we’re only going to see an acceleration of these trends. So, for those that have experienced, for those that are.. There’s a great opportunity to continue to compound returns, but it’s really just an opportunity and it’s really difficult and you have to execute on that as well. So, we’re excited and we think that the next ten years or so and even the next five years have a real chance to be even more chaotic than what we’ve seen recently. So, for stock pickers, we think it is a great environment.

A shout out to Stream by Mosaic

[00:03:36] Tilman Versch: Tilman here.

I want to give a loud shout-out to Stream by Mosaic. Stream is a super helpful tool for every investor. Stream offers a great transcript library. And it is getting better day by day. There are three reasons why Stream could also help you: 1. Getting up to speed quickly on new investment ideas – 2. Generating new investment ideas. 3. Staying up to date on existing investments.

If you want to try it, you can do it 21-days for free. Just go to start.mosaicrm.com to start the free trial today. With the promo code Good Investing you will also get 20% off for the first year. So, please give it a try under start.mosaicrm.com. With the code Good Investing you will get a 20% discount for the first year. You can also find the link and the code in the show notes below.

I want to show you a chart and I want to hear your opinion on it. And if you discuss this kind of chart in your firm. It’s a comparison of growth and value. And so, are you discussing this kind of chart? And also, what is your implication, if you discuss it in your firm?

Value vs Growth: How Worm Capital sees it

[00:05:02] Eric Markowitz: This is not like a specific chart that we would probably weigh too much importance on. I think our perspective would be, while the companies that we typically are attracted to and invest in, which are typically higher growth types of models, the distinction between growth and value is somewhat semantic. Certainly, the performance attribution that you showed, shows a specific diversion in the performance relative to the type of company, but that’s why I think we’re so focused on being concentrated in the right names because we’re going to continue to see this big dispersion of the big winners and potentially the big losers as well.

So, in our view at least, this tends to be a pretty winner-take-most type of marketplace. There’s just an acceleration effect that we see taking place as well. So, I think, from our perspective, that’s not something that we try to overweight in our thinking or our specific strategies. We’re ultimately just trying to find the best business models in the world that have the ability to compound out for the next ten years or so. So, it’s obviously something that comes up in discussion and maybe Dan, if you want to touch on that, but I wouldn’t give it too much importance for us right now.

[00:06:23] Dan Crowley: Yeah, obviously interesting. And the inversion that you’re seeing, and then there are specific time periods where they’ve got more dramatic. From our perspective, we’re really solely focused on business-level value proposition and go-forward valuations. If we thought that there wasn’t going to be a precipitous decline in some of the companies that we had less favorable opinions on, we would obviously move in that direction.

But everything from us starts and ends from a business perspective and then moves on to the valuation perspective on a go-forward basis, not a backwards basis. And when we see obviously, we’ve seen certain, let’s call it, frothiness in components of the market that we’re invested in, but not specific companies that we’re particularly invested in. So, from our perspective, it’s really focused on the business and there are several market dynamics that haven’t historically been present in terms of winner-take-all or winner-take-most dynamics and so on and so forth. So, the interesting chart, all good stuff, but for us, all of our valuations are on a forward-looking basis and we’re just really obsessed with the customer-level valuation and things like that.

Why Arne couldn’t participate in the interview

[00:07:52] Tilman: Some people would have expected Arne here, who’s also the founder of your film and the brain behind it. Why couldn’t he participate in the interview?

[00:08:05] Eric Markowitz: I think… I just spoke with Arne earlier today. He’s focused on the portfolio. He is truly not a guy that loves publicity. I think his kind of comfort zone and happiness is really a 24/7 obsession on the book, both kind of monitoring current positions both on the long and short side and looking for new opportunities. But he’s not out there trying to do too much marketing or publicity, so, he’s comfortable kind of doing what he likes doing.

[00:08:40] Dan Crowley: Yep. And yeah, I appreciate you putting up with at least myself. I think Eric looks great. From us, everything that we try to do is… it’s pretty difficult to get an edge in this environment. And even our competitors that we disagree with their investment positions, we still respect everyone that’s doing this because it’s extraordinarily difficult. So, you know what, where we can pick up small edges and small advantages, and for that, it’s not having our CIO necessarily do a ton of publicity and being able to, because we’re looking at long-term investment horizons, think relatively slowly and methodically without a wide array of distractions. For us, we think that’s the best use of our investment resources for our partners.

What do Dan and Eric do at Worm Capital?

[00:09:32] Tilman: Maybe at this point, I also want to ask you what your roles in the firm are. I already started without an introduction, but maybe now is the point that we get some background on you, both of you.

[00:09:44] Eric Markowitz: Yeah, absolutely. So, my title is director of research. I come from kind of a unique background, perhaps. I was an investigative business journalist and business reporter so..

I essentially went to school in New York City. I wrote about technology firms for magazines, like Inc magazine, later Newsweek articles published in the New Yorker. My focus was always on technology companies primarily, and in doing that I got the chance to interview probably hundreds of CEOs, high-level executives at technology companies. But on the flip side, I also spent plenty of time working with and speaking to different venture capitalists and some public equity investors. And so, having gone to school for both business and journalism, I think my perspective was: Wow, I love writing about these high growth technology firms and eventually wanting to be able to participate and invest in them and so, about coming up on, well, five years ago, Arne and Dan had just kind of launched Worm Capital.

Arne had read some of my reporting. I think specifically he may have read a big cover story I did on Aaron Levie at Box which is now public, but when I wrote about the company it was still private, and was looking for some research help and looking for maybe a bit of a differentiated type of research style. So, we really like to go deep, fundamental research, understand sort of the components of an industry, who all the major players are, really on a deep fundamental analysis basis. And so perhaps those skills as a reporter and someone who can get kind of obsessed with companies and industries and go deep on something, it translates kind of interestingly and I think well to, to the investing side. So, that’s what I’m still doing today. I’m working with Arne and Dan on research primarily, and I think our perspective is having come from the world of media. It’s incredibly difficult right now, I think for not just individuals, but investors, especially to kind of separate the noise from the signal. So, we’re constantly inundated with information. And one of the primary skills that I think investors need to develop and really kind of focus on is being able to separate what matters. What’s the headline that actually is driven by some fundamental issue and versus what’s noise? What’s clickbait? What’s something that’s maybe going to capture the new cycle for 24, 48 hours but is ultimately not relevant and not material?

So, a lot of my day is just spent looking for new opportunities, trying to sift through sort of the current data landscape, and ultimately focusing on the companies that we own and are looking to own over the next few years. So that’s the high level of my role, but obviously, we’re a pretty small or, Dan does research as well. Arne obviously spends most of his time on research. but I’ll kick it over to Dan and to kind of give you his background.

[00:12:49] Dan Crowley: Yeah, nothing crazy exciting. Basically, my undergraduate degree was in molecular biology and I wasn’t really cut out for lab work. It was a little boring for my liking and really liked the multi-factor element that you get in basically investing,

But when I first got into it, at a relatively low-level position, and I had my CFA and I got a Master’s in Science and Investment Management, I was pretty shocked by the kind of legacy work done by academics and things that were presented as scientific fact that just clearly were not the case. And at the same time that a significant portion of the industry itself is more of a marketing machine than an investing machine. So, I was always attracted to individual investors who had done their own thing and had kind of carved out their own niche. And especially if they had gone against the grain and done it all by themselves.

So, I was working at an RA in San Diego, where Arne was living at the time. He had been kind of a lone operator himself just working 24/7 and he had done a significant amount of writing. And I was just, I was like, this is the guy I was extraordinarily impressed with his ability to go against the grain, the deep work, the, frankly, lack of BS that we see in certain cities in the United States, and I was immediately attracted and wanted to work together with him to build a bigger firm and allow more opportunity for outside investors. And that’s just kind of what we’ve been doing. And I’ve worked with Eric and it’s a relatively flat order structure.

I do all the trading and from our perspective, we think that conviction is basically how you generate returns, and getting conviction is extraordinarily difficult to do. It’s a lot easier to farm out gigantic analyst teams and have investment committees but from our perspective, that’s the way how you get middling returns because you start moving towards the average. So, it’s been a great kind of adventure, and again, as we’ve kind of alluded to previously, we think our strategy is well set up for the next 10 years or so and every day is new and there’s something to learn at all times. It’s been great.

How to filter noise and signal

[00:15:30] Tilman Versch: You mentioned the filtering out of noise and signal. Is there any hack you found or any good way to do it?

[00:15:38] Eric Markowitz: No. And if you have a hack for it, please let us know. I think the best hack is…the only one I’ve come up with is time. So, time and patience and I think the curation of people you follow, of sources that you respect.

I think that if you spend enough time looking at anything it’s like a puzzle, you just have to sort of take your time to put the pieces together. And that’s kind of what I’ve found across the media landscape is that all the articles that come out, they all come from some genesis of an idea of an editor that has an, there’s some sort of nugget of where everything is coming from and trying to locate the truth and all of that.

What actually is the truth behind the story? I think that’s sort of almost philosophical question, but one that is immensely challenging. and I think if I had a hack for it I would probably license that hack and focus on that, but ultimately, I think it’s just time and patience and sort of knowing who to follow and who not to follow.

[00:16:53] Tilman Versch: Yeah, but maybe also about….

[00:16:56] Dan Crowley: Yeah, I would just tack on. One of our core firm principles is that we don’t necessarily believe in complexity. We just try to break things down to pixel level and then build up and I think that when we read, we read the contra opinions of everything that we do, maybe 50/50 on things that are in agreement or maybe more, and some of the mistakes that at least we perceive people to be making is they silo themselves into only reading things that are congratulatory or almost conspiratory type information.

So, we read everything …we read things that support our thesis, things that don’t support our thesis, and then try to constantly test that. But in terms of a formula, one of the things that, because it’s not easily quantifiable, it’s not easy to hold, is that the relative value of qualitative work in investing has long been denigrated as unimportant to modeling which we view a lot of quantitative work as commodity work. So, we think that that’s an edge that people can pick up and it’s not something that you can necessarily break down into Y equals MX plus B or something like that.

What does Worm Capital’s new approach mean?

[00:18:17] Tilman Versch: One thing I find helpful as a kind of hack are the mental models or the frameworks where you’re hanging your data up and building them. And I have quite an interesting quote by Arne or from your letters added by Arne:

It was early last decade. I developed our current strategy from scratch. I realized that the new paradigm shift in technology needed a new valuation model, a new approach.

What does that mean? This new approach?

[00:18:44] Eric Markowitz: Yeah. So, all value from our perspective is future value. I think what our sort of overall philosophy is, is that especially in industries that are undergoing a rapid shift where you’re going from technology A to technology B, requires a fundamental new framework for analyzing these business models. So, it’s no longer relevant from our perspective to try to slap on a PE ratio or look at some sort of backward-looking metric to figure out future value. And so, I think in the short term, especially across the type of universe of names that we look at that are particularly in the high growth business models where we see a lot of our competitors, maybe, trip up, is they get stuck in this framework of analyzing businesses using these metrics that are inherently backward-looking.

And just to kind of push along with what Dan was getting at earlier, it requires, we think at least, sort of a more focused on qualitative analysis to understand not just what’s happening today, but ultimately where the customer is most likely to go in the future. That really requires an intense understanding of the value proposition.

And so, when we spot something that maybe looks, from a traditional perspective, overvalued or something that’s complex, we’re actually drawn to those industries because, in that complexity, that’s where actually we can gain an advantage. I think another sort of Arne philosophy is that he’s a big Buffet and Graham fan and would say that he agrees 99.9% with what Buffet has said, except for the concept of circle of competence. That’s one area where we think that when investors get siloed into staying within their circle of competence, that enables us to get an opportunity and an edge by drilling into it because they’re there ultimately, as Dan said, there, from our perspective, there is no such thing as complexity. That is our job is to break down complexity into its bare essentials and understand what’s actually happening and put the pieces of the puzzle together. So, our valuation frameworks really are sort of industry and company-specific. They tend to be more forward-looking; they prioritize different elements of a company’s business model. We really focus on high growth models, margin expansion, but certainly, as Arne would say, tricky valuations. We like tricky valuations, that’s actually where we can get an edge.

[00:21:18] Dan Crowley: Yeah. Arne’s background was kind of, is a cigar butt style turnaround stock investor, but things aren’t the same as they were 50 years ago where some company might have an asset thatwas 2x their book value and it just, you could just highlight that and it would double. From our perspective, he needed and we needed an investment framework that optimize the inefficiencies of the market that we’re looking at now. And as Eric alluded to, you can’t just use a simple DCF in these messy environments. So, the models themselves become more basic, more vanilla, more traditional as the company grows, but the greatest opportunity for asset mispricing is when things are the least clear and from that, we focused really heavily on different metrics than you would use historically. And at the same time, if we’re looking at competitors, just because something has happened in the past is not necessary to repeat in the future, always the good financial tagline. And we think that there’s a couple of market dynamics that are not being priced even accurately to this day.

One is that because of the proliferation of information, the relative lack of geographic boundaries that we’ve seen historically, that we’re seeing increasing massive concentration in select companies. So, you have to pick that company and its secondary competitor. Whereas I think, as this space has become more attractive I think to more traditional investors, they want a broad basket of companies in a specific vertical change. And from our perspective, that’s a mistake.

But at the same time, you have to build conviction, and building conviction is extraordinarily difficult and time-consuming and you really have to do it over a period of years. So, there’s clearly value in these spaces and we have to build a unique valuation framework model so that we are comfortable holding these specific positions where you can’t rely on more convenient shorthand metrics.

What kind of companies do they like to invest in?

[00:23:44] Tilman Versch: Do you like to own stable companies or what kind of companies do you like to own?

[00:23:51] Eric Markowitz: So, I think that, I think maybe first distinction is, businesses that we focus on and like to own tend to grow actually fairly linearly the growth of the companies that we own, we like to target companies that are generally overgrowing top line over 20%. I think that, in terms of stability, the market will throw prices at those businesses that are not stable. I think that what we find is that the businesses that we own are actually growing pretty stable, that there’s immense opportunity for expansion specifically within maybe their core business line but opportunities for expansion outside. But the market misprices those on a day-to-day basis and so we have to separate, as a firm, business risk versus price risk, and so maybe that’s not exactly the question that you were getting after, but the businesses ultimately that we like to own are growing extremely fast and stably.

And there’s not too many of those businesses actually. And I think that’s maybe the fallacy that people fall into is, believing that maybe there’s 50 or 60 businesses out there that have huge prospects and are growing stably and over 25% year over year at a significant scale. There’s just frankly not that many opportunities out there, which is why our strategy really does prioritize a heavy concentration and I’d say high bar to enter into our portfolio.

[00:25:27] Dan Crowley: Yeah. I might just tack on, clearly, for us to generate successful returns, we have to be able to buy an asset that’s mispriced. If we look at a stable industry, as we denigrate these kinds of traditional valuation frameworks, they’re pretty good and the market’s relatively efficient in those spaces.

So, in a vertical that has predictive cash flows, it’s relatively difficult for us, in my opinion, any money manager to get an exceptional advantage over their peers. You’re just kind of really trading around the margins. Whereas when we look at the opportunities in these messy spaces, and again, you have to be right, there’s the opportunity for very significant returns and there’s an opportunity to gain a pretty sizable edge over your competitors, again because you can’t just use simple valuation models, it all has to be forward-looking and you have to be able to build confidence in your own models as opposed to just, it’s easier to look out what happened the past five years, throw a simple run rate on it and then discount it back.

What role does historical data play for you?

[00:26:40] Tilman Versch: What role does historical data play for you?

[00:26:44] Eric Markowitz: I think we, of course, that’s a good question. So, historical data is extremely important. Right? So, I think that it’s all a question around how much we emphasize historical data into our actual evaluation framework. So, just because a company was able to establish itself and grow to a certain size in the past, certainly in this environment does not necessarily mean that they will be able to continue that growth into the future.

I think that this is really what we’re seeing from an industry perspective, which is a consolidation. Over time, the market has standpoints, obviously is quite efficient in the short term though, I think the market does have a bit of a challenge actually understanding the consolidation of effect into one or two of the select winners, and when you consider, all business and all value proposition is generated today and into the future historical data actually doesn’t really affect, sort of customer level value proposition.

So, on a very basic example, if you have a business that had a great product for 30 years, a competitor comes into the marketplace with a lower cost and more efficient product, the historical data around your product sales for the last 30 years can be rendered pretty meaningless overnight, and so, that’s the danger that we find in this marketplace. And frankly, a lot of the danger embedded within, a lot of the passive strategies that just hold huge baskets of stocks is that because of the sort of cost curves and the accelerating impacts of these technologies, some of these business models can be rendered pretty obsolete very quickly.

That’s a challenge. That’s a significant challenge. Not, certainly for us, but for any investor today is accurately sort of, sizing up how much of the emphasis of historical data and historical success will really carry over into future value. You see that playing out with certainly in the energy industry with a lot of these old oil incumbents saying we’re going to transition our business models. Well, if you look at sort of the history of business, the incumbents very rarely are able to successfully transition business models. They will put up a fight and they will put out many marketing press releases, but ultimately you have to look at where their cash flows are coming from.

And if they don’t truly shift capital allocation to the new paradigm, this is why blockbuster companies like Blockbuster just ultimately are rendered obsolete and it happens pretty quickly. So, I think that’s the danger of looking at historical analysis and pricing it too high in your framework, is you get stuck in legacy thinking, and in this environment, we think that can be pretty dangerous.

[00:29:29] Dan Crowley: Yeah. I might just tack on. I obviously agree with what Eric said in stable industries, so it can be incredibly useful and prescriptive of the future, but in what we do, and we really only focus in these messy areas of the market, it could have zero value. I guess the only value I would say is that, even if there is a superior economic model, people’s consumer, either people or business, consumer patterns are still relatively slow to change. So, for us, that’s great coz you can compound growth over an extended period of years and it’s relatively more, it’s still lumpy, but it’s over an extended investment horizon. And that’s one of the interesting things that, from our perspective, the pandemic has changed is we’ve seen a pull forward probably a couple of years of rapid consumer behavioral change, if not more. So, it depends on whether it’s in a disrupted vertical or a stable industry. And maybe, the only value that you can get out of it is the pace of change. And even if things are moving at relatively fast rates, it still takes a while for a complete changeover to the new business model

The top sectors in Worm Capital’s focus

[00:30:57] Tilman Versch: With your investments, you are focusing on I think five sectors, energy, transportation, retail, cloud computing, and digital entertainment. What sectors, or what two sectors out of these five are your top sectors?

[00:31:15] Eric Markowitz: I would say, energy and transportation would be our top sectors right now that we’re focused on.

[00:31:20] Tilman Versch: And why these?

[00:31:23] Eric Markowitz: Simply as a function of the enormous change that we forecast happening over the next 10 years. So specifically, within energy what we’re seeing is a total disruption across the energy landscape moving from a system that has historically relied on extraction of fossil fuels to a system that is primarily based on the collection of wind and solar, through storage and then distribution over a decentralized grid. And so, there’s a lot to unpack within that framework, but ultimately, we’re so focused on it right now because we just think everything is moving towards a renewable paradigm. And has, from our perspective, very little to do, certainly, we follow all the political developments, but from a value proposition and perspective, the costs are lower, it’s more efficient, and it’s only a matter of time from our perspective, at least when we make a full transition to this new paradigm.

And so, within that category that’s obviously solar and wind, but also, battery storage, it’s energy, software, and virtual power plants. And then of course on the transportation side, that’s an enormous sort of force function for us and focus area. The disruption from internal combustion engines to electric vehicles, autonomous transportation, pretty much any modality of transportation, we think is going to move towards renewables and autonomous. And so, for us, this is the area to be focused on for the next 10 years, if you’re looking for opportunity. It’s attracted a lot of attention, it’s attracted some frothiness in the market, but ultimately, we’re so focused on those two areas as it’s just a function of how much opportunity there is to be disrupted.

What gives you confidence?

[00:33:20] Tilman Versch: What gives you the confidence that this new paradigm will come true?

[00:33:26] Eric Markowitz: It’s, from our perspective, just a function of cost and efficiency of the technologies. So, to talk about electric cars, it’s a cheaper, more efficient mode of transportation. For many years, cost was the limiting factor and battery production was the limiting factor and battery energy, the density of the batteries was limiting factors. We’re still not there yet, we haven’t, as Arne would say, totally crossed the Rubicon, but that’s what makes it frankly kind of exciting and challenging. But if you look really kind of on a deep historical and sort of fundamental basis, the technologies have improved rapidly over the last 10 years. That gives us a great deal of confidence that ultimately, we are transitioning to this new energy paradigm.

[00:34:20] Dan Crowley: Yeah. And just to tack on Eric’s earlier first point, if these economics are more compelling and we do move in that direction, if you start to think of the secondary and tertiary effects of all that, it’s almost mind-blowing how much opportunity that is and how much upheaval, primarily in a good way that will be, we could even, it’s not really investing based, but if you look at geopolitics and all around the world and where countries are deriving the revenues, it could be the greatest transformation and also, transfer of market cap that we might see in our lifetimes. And just to tack onto what Eric says, in terms of technology improving, the cost compression and of what we’ve seen over the past 10 years, generally speaking, when you look at the forecast that all these big agencies put out, at least historically they’ve been linear, right? Whereas nothing really happens linearly.

So, when we focus on the non-linear compression of cost and the nonlinear rate of adoption, that’s where we start to really get excited about these opportunities. And that’s where technology has been adopted for a relatively long period of time now and there’s incentive so, we can go on and on, there’s a lot to unpack and we’re talking trillions of dollars that will either be made and simultaneously lost.

Are you shorting in the energy sector? And why are you shorting?

[00:35:54] Tilman VerschVersch: You’re also shorting. Yeah. Sorry. You are also shorting and trying to stay away from certain business models. Are you shorting the energy sector and maybe you can also add some light on why you are shorting besides just going long?

[00:36:14] Eric Markowitz: Yeah. Maybe Dan can talk a little more about the specifics of just portfolio construction as it relates to the shorts, but I can talk a little bit more of the philosophy behind it.

I think ultimately any business model that relies on some legacy fossil fuel asset as its main source of cash flows, we think will ultimately be disrupted. So, this ranges from companies that are focused on combustion engines to trucking companies, even down the value chain towards auto dealerships, auto parts retailers.

So, we’re looking for companies that ultimately will be rendered or could be rendered obsolete in the next 5 to 10 years. So, that’s the framework of how we think about how do we find an attractive, short opportunity obviously, and maybe Dan can talk a little bit more about this.

Equity markets it’s very difficult to actively short right now. And I think it requires an immense focus on risk management, position sizing and so on. And so, but frankly from an industry perspective, I’d say we’re looking for coal companies, oil companies any company across the energy landscape that ultimately just can transition its business model.

[00:37:34] Dan Crowley: Yeah. It’s been an interesting year for the short book. One thing I’ll say is, if we look at our strategy, it’s a natural pair trade where we look at basically the dominant winners and then there’s a, let’s call it a handful or a basket of losers that we see the market cap being swallowed up into this new player in the field. So theoretically that produces a bit of a melting ice cube. And when these precipitous drops in core price do happen in the market prices in the forward-looking valuation, frequently it happens very quickly. So, you have to be in position and that’s what we want to do.

So, that’s kind of the high-level strategy when we talk about more of the past year or so, and what we’ve experienced last March and we took off a decent amount of risk in our book. And simultaneously increased our short exposure as we followed the pandemic from Asia to Europe and ultimately its global destination.

And for us, it allowed us to have a successful March. We ended up paying for that hedge in April and May, but we were comfortable because to some degree and I think anyone would be lying if they knew perfectly well what was going to happen. So, if you’re driving a car and you can only see X feet in front of you, you have to act accordingly. So, when we basically saw the really high level of support that the Fed was going to get, and the fact that there was pretty tremendous single name-risk, and individual short positions, we spread out our names far more than we typically have. And we typically have small short positions anyways just due to the nature of the trade.

So, the other thing too is that there’s no way to get familiarity in those names overnight. You have to study them for years and years and know their respective weaknesses. We had an article on American Airlines in 2016 or 17 or something like that, buying back their shares fresh out of bankruptcy and putting themselves in a vulnerable position in any sort of adverse economic effect.

So, for us, we see it as two sides of a trade and that we’d like to profit on both, but I’d be lying if I’d say that the past year it hasn’t been hard to generate really significant profits on that.

Why the effort of shorting?

[00:40:18] Tilman Versch: But, help me to understand, if you have identified the winners and those winners could go up tenfold, why the effort of shorting? Because the return you can get is limited and you always have to find new shorts.

[00:40:35] Dan Crowley: Yep. Yep. Obviously, the return profile is asymmetric, right? So, you can lose it unlimited and you can only make a hundred percent, which you’ll never make anyways. Again, for us, it’s nice to have that hedge in times of chaos. it’s a comfort to our partners and us. We can limit the damage or at least attempt to limit the damage. And again, with all the work we do and everything we put in, we’re trying to generate the best absolute return that we can get.

And if we think that we can pick up some more returns from that portion of the book, while at the same time maintaining some sort of a basic hedge, we think it’s an attractive proposition.

What are the principles of your company?

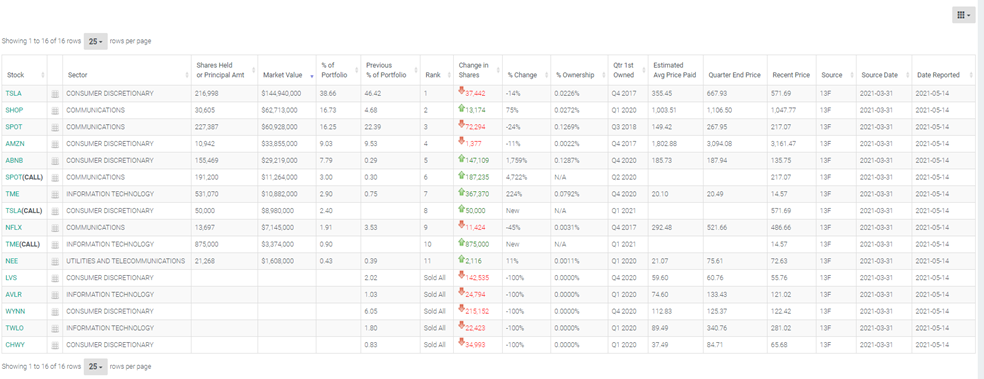

[00:41:26] Tilman Versch: Maybe let’s take a look at your portfolio, here we go. This is publicly disclosed. And just like from the upper level, looking at the portfolio, when I try to read what are the principles besides what we already have discussed the flow and the thinking of your portfolio to position sizing? What are those principles?

[00:42:01] Eric Markowitz: Yeah. So, generally speaking on the long side we’ll own anywhere between 5 and 15 names. We’re historically pretty comfortable as long as the opportunity merits it to be pretty heavily concentrated in a single name or two, potentially up to 25 to 40%.

That’s a pretty rare occasion and I think we’ll only have a few of those over the lifetime of our strategies. On the short side, as Dan pointed out, we’re certainly going to be more heavily diversified. I don’t think those public disclosures really do our portfolio justice, because I think there’s just some inaccuracies embedded within the 13 F filings, and so, but across the short book we’ll have anywhere from 50 to 85 names, roughly speaking, and we like to be concentrated in what we believe to be the most disruptive business models in the world.

Over a longer time horizon, we believe that this is the best way to compound wealth on an absolute basis for our partners. Certainly, I think in the more traditional academic view is, this will increase the volatility of your strategies and therefore increase risk.

Our perspective is that headline risk and price risk are just fundamentally not the same as business risk. And so what we want to do is just truly ownthese companies for the long-term. It requires an immense amount of conviction. It definitely requires patience, perhaps a bit of a contrarian mindset, and a focus on valuation.

But ultimately, we believe that, especially in this sort of environment in which there’s a lot of change happening quickly, that is the best risk-adjusted way to deliver returns for our partners is to be pretty select in what we own. And we’re able to withstand the sort of monthly, quarterly, even yearly volatility in pursuit of these truly absolute long-term gains for our partners.

It’d be lying if I’d say it’s not a challenge. Obviously, this is the hardest game in the world. It certainly is and certainly to kind of, when you see a deviation in the price on a big position, a drawdown which are bound to happen, it forces you to really stay focused on what the competition is saying, what the sort of contrarian thesis is, what’s driving the price action and then obviously, we’re always looking for and spending years developing conviction on the next disruptive opportunity. So, we don’t get to a 40 or a 25% position overnight. It takes years of research and understanding of these business models to really build up to that position size.

[00:44:55] Dan Crowley: Yeah. And I totally agree, just to kind of like go back to what we’ve been talking about previously in valuation and how these things change over the life cycle of the specific investments that we look into. We have respect for our competitors in the space and we have respect for people on the contra-side of the trade.

Ultimately, as these businesses mature, they become relatively easier to value. So, that is, in many ways that closes the delta between what we believe is the intrinsic value in the traded quote price. So, if we’re converging on full valuation obviously the sizing of the position isn’t as attractive as it once was, right? Because there’s only so much room for it to grow. So, for us, it’s opportunity and its life cycle of these kinds of disruptive verticals. And one of the relatively nice things in our strategy is that, while we do kind of specifically focus on five verticals, everything we do is on a multi-year basis and they’re at different life cycles of their progress.

And in terms of opportunity as well, we think that these disruptive events will ultimately tap on basically every component of the modern global economy. So, if the markets weren’t efficient, then that wouldn’t work out over an extended period of time. So, a lot of it comes down to opportunity and development of the transition from one business model or one economic model to a newer economic model.

How does your digging work?

[00:46:38] Tilman Versch: In the snapshot, we saw a certain activity in the disclosed information. Like there were only two positions where there was no change visible in the positions. What leads to this activity and what makes you, for instance, sell?

[00:46:57] Eric Markowitz: Yeah. So, I think one of the things, I’ll get into that in a second, but what we like to do is really, I think philosophically, let winners run.

I think that what we see happen pretty often, and certainly, something that Arne is really focused on is letting these companies run to ultimately, as Dan alluded to, what we view as their fair value, which can take really a period of years. And I think that there’s a lot of temptation to sell. Certainly, we see a quick pop, but we stay focused on sort of the long-term valuation. As far as when we do sell, it’s a variety of metrics. Sometimes it’s as simple as, well, it could be sort of a tail risk event like March 2020 when we just wanted to take risk off the table.

It could also be just a function of a new opportunity or an existing opportunity in the portfolio that we want to augment. So, we will transfer from one position to the next, given the opportunity set of the valuation. So that’s another, and I think really it is a focus on, just applying capital effectively into these companies where we’re meeting where we want to be, where they can hit certain valuation frameworks and goalposts that we’re tracking.

And also, as we develop conviction in these positions, we want to add to them over time. So, that also forces some selling from lower conviction or lower opportunity type of positions that have reached more of a fair value. But maybe Dan, I don’t know if you have any thoughts there that you wanted to add on?

[00:48:31] Dan Crowley: Yeah, nothing crazy there was no fundamental investment, DCS changes kind of optimization. And then, from our perspective and really Arne’s hyper-life-work focus is to put out the best portfolio possible. So, we don’t use a crazy amount of leverage or anything like that.

So, there’s some kind of tweaking around the margins that we’ll do because we’d never want to think of ourselves as satisfied and or happy with what we did in the past because the past is gone. So, all we’re good for now is what we can do going forward. And so, kind of little tweaks and things like that which may not seem completely material. First, we think if we can pick up any sort of returns, that’s great. And then, we also think it’s an attractive mindset to always try to put out the best thing that you possibly can. And even if that’s focusing on the third decimal point of a short or something like that, obviously without spending too much time. But it’s kind of a mindset. We didn’t fire up the computer and turn one of our longs into a short or anything like that.

What digging did you do for the big positions in Tesla?

[00:49:56] Tilman Versch: You already mentioned that the digging you do before you invest, and that might take years. Maybe you can explain a bit of the digging you did for your biggest position for Tesla. And can you walk me through the process of falling in love with the big position in Tesla?

[00:50:17] Eric Markowitz: Yeah, sure. So, I think one way Arne likes to kind of talk about just this process of digging and observation is, it was Jane Goodall’s sort of famously just observes the chimpanzees, right?

Just sits on the hillside and just watches. And I think that’s our approach to a lot of industry observation for a period of years. We don’t take an opinion. We don’t really try to have a strong perspective on something. We just watch as objectively as possible. I think when it comes to a big position like Tesla or Amazon before it, which was another, is a current position, had been a much larger position in towards the inception of the strategy, what we saw with Tesla, and continue to see, is a massive opportunity to completely reorganize the wealth pie across transportation and energy.

And we think that, historically, the sort of analysis that we’ve seen on the company, you can kind of go back all the way, 2012/13, analysts were kind of talking about the company as they are today, just fundamentally I think misunderstanding a lot of the key aspects of this. It’s a really tricky valuation. It’s a really tricky company to truly understand and it takes years to kind of develop a thesis around it. Anyone who comes to this company overnight just looks at it is likely not going to understand it. So, in terms of the actual fundamental research that we do, we do everything possible. So, Dan and I have taken visits out to battery factories. We speak to auto dealers. We go to the industry auto shows. We go down, Dan thankfully has a good science background and we drill down into the chemistry of the actual cells and understanding how these battery packs work, what gives Tesla an advantage there.

So, from our perspective, the work is really never done. This is like the ultimate puzzle to figure out how the next 10 years of transportation is going to be reorganized in the new electric-first paradigm. And so, from our perspective, Tesla’s maybe one of the most misunderstood companies out there. That gives us, definitely, an opportunity to take a sizable position on a really misunderstood company. And as far as thesort of level of research that we go into the competitors, specifically to Tesla, as well as the analysis, we’ve vacuum it up constantly.

So perhaps, I think what Arne would say is, like in chess or in poker, you know your hand. You know the pieces that you’re playing with. But what’s potentially even more important is to know what your opponents are thinking and to develop a thesis based on maybe some flaws in their analysis to gain an edge or conviction there. So, a lot of our time is spent really just going through the contrarian thesis, understanding why people are maybe bearish on a position like that, why people may be short, and though we may disagree, we certainly have respect for anyone that puts up capital to express their view. It takes years to develop a conviction on a company like Tesla just as it did, the companies like Amazon and Netflix and some of these, in the moment, pretty contrarian type of positions.

[00:53:42] Dan Crowley: Yeah. We certainly didn’t do it for our health. And, but yeah, one of the things is there are certain things that are demonstrably facts. Right?

So, when we look at prismatic versus cell versus pouch, different batteries, even when we look at who’s investing down the supply chain? Who’s investing in battery factories three or four years ago? Who is just PowerPoints? We went to the LA auto show. You can do simple checks. Their big hyped EV product isn’t even there. And they don’t know when it’s coming. From us, we looked down the stream, well, you’re not purchasing the necessary components to either make batteries or get batteries.

What is the effect of outsourcing your core competency if you’re a legacy OEM to an Asian battery supplier? Are you nearly as, what’s your moat that you used to have if your traditional skill is combustion engine production and then that’s being outsourced? A lot of the mistakes that were made were saying that all of these companies could just flip, and It’s still being made, could just flip a switch and then go from one completely different way of doing business to a completely.. It’s very, very difficult.

And if you saw the growing pains and even when we look at all of the different business lines that, we think respectively have tremendous opportunity for creative value growth, the market just oversimplified it. So, for us, it was really focusing on the technology, and that allowed us to then handle the deluge of information, say, well, okay, nine times out of ten, that’s not material. Or that’s just a great headline because we know the underlying business, we know the underlying technology and we know who is actually moving ground and who’s actually just making PowerPoints. If you look at, I don’t really want to denigrate like people but, it was very surface level and so, for us, that’s opportunity. If a gigantic portion of the market is against you, and you see a very tremendous opportunity, and so, you’re able to purchase at relatively low prices, that’s kind of all you want as an investor. It doesn’t make it easy. It’s extraordinarily difficult.

And you have to kind of have a compulsion to really want to generate returns, so, it’s slow. And even when we look at a lot of the players in the full self-driving or autonomous space, we feel very, we felt comfortable years ago that vision and radar where we’re going to be superior to the LIDAR and mapping paradigm. So, It’s a lot of things that kind of add up and it allows you to feel, I don’t know about comfortable, but confident in your decision-making process.

What else is misunderstood in Tesla?

[00:57:07] Tilman Versch: What else is still misunderstood in Tesla?

[00:57:11] Eric Markowitz: I think, from our perspective, what we really like to find in companies is customer obsession. So, if you just look historically at really some of the most successful businesses out there, it really starts with the customer. So, we’d like to see, both literally and metaphorically, customers lined up around the corner to get the product. And I think what perhaps is maybe most misunderstood is, a little bit what Dan is getting at, which is how challenging it is to create a complex manufacturing output at scale.

So, this is something that we look at pretty closely, right now especially, as we see a flood of new entrants into this market of prototypes. Now, prototypes are, they can look really great, especially on a slide deck. And maybe even in a presentation, you bring a prototype out on stage and you can maybe drive it around. That’s great.

There’s a lot of enthusiasm right now for prototypes. And that is, I think, where we’re going to have a lot of problems in the next few years. So, what’s really challenging about the auto business is complex manufacturing at scale, and having enough of the supplies to actually reach those pretty lofty goals of production.

Very few auto manufacturers from our perspective are gearing up for the crunch of supply and manufacturing capability that will enable the type of output that they are predicting. That goes all the way down into the supply chain that’s required. And so, I think if you’re an investor in this space, what you really need to focus on is who is best poised to succeed given their capabilities today. That’s what you need to ask. And then also, ask, what are they doing if they’re not prepared today? What are they actually doing to prepare for that output? And that’s not just, I would say, in the hard materials or hard technology, It’s the software as well.If you look at some of the competitors, and this isn’t necessarily even just full self-driving autonomous setting, that aside, if you look at the type of software platforms that are being utilized in some of the new electric powertrain platforms, I would take a real close look because we certainly have, I’ve tested the competitors and looked at their software platforms and the ability to kind of send over the air updates onto those cars.

And that is going to be a really difficult transition for some of these OEMs. I think, broadly speaking, the more misinformation and sort of, marketing statements from the competitors, frankly, the better, because as Dan pointed out, we’re comfortable with some short-term noise and misinformation as long as we’re focused on the business. We’re not really too focused on what an executive would say. Arne has a sort of great idea about executives, they’re gladiators in the Colosseum. They’re going to say what they’re going to say to make them sound tough. It’s also paired with, the only way to develop this conviction is to be open-minded enough to actually test out the competitors and to want to believe and to go down that path of analyzing the competitors of the business. If a competitor of Tesla, either a new entrant or an existing incumbent comes out with an incredible product that’s winning among customers, we want to own the best businesses of this dynamic.

And so, we’re open-minded to some of the new, especially some of the new upstarts that are interesting to us that are actually developing the capabilities to produce the output that are actually having the hard talks around, okay, we need to actually build up these manufacturing facilities, those are more interesting to us. But still, it’s a minefield and I think a lot of the companies that are coming to market today with electric promises, we’ll see where they are in the next five, ten years, but it could certainly be a winner take-most type of dynamic, just given the complex manufacturing and how difficult it is to scale up these businesses.

[01:01:26] Tilman Versch: Do you want to add something?

[01:01:28] Dan Crowley: Sure. Yeah, from our perspective, one of the most important things is software, right? So that leads to the possibility of, pretty heavy, gross profit and very successful cashflow and when we look at the competitive landscape, we’re still not overly impressed.

And then if we look for driver’s evaluation going forward, again, the energy software component, the battery company component, auto bidder, and then the real, potentially greatest step changes is the full self-driving and what that can mean. And then the market is still, at least inour opinion, pretty unsophisticated on the different paths that companies are going on.

Eric, you’d agree on that, right? In terms of when we look at with pretty heavy valuations, we think they have a chance to be at zero in some short order. We’re not looking to get in front of those trains but it’s completely different technologies. And then the difference in data accumulation, it’s a flywheel effect that is only going to increase. So, again, there’s a ton of misunderstood. and we look at three or four different business lines that we think can be quite large,

Where did you get the idea to invest in Spotify?

[01:03:10] Tilman Versch: Another quite big position of yours is Spotify. Where did you get the idea from, to invest in Spotify?

[01:03:16] Eric Markowitz: If any investors are curious to sort of read a longer form piece, we have published something that, if it’s not available on our website, qualified investors can get in touch, which I think goes into the longer form thesis. But I think what we saw with Spotify was an early recognition that what Daniel Eek, the founder of Spotify, was building. His early insight was that, just as video is a trillion-dollar opportunity, that there’s no reason that audio can’t be a trillion-dollar opportunity as well.

I think when we just take a step back and look at the, think about the types of businesses that we’re attracted to, we like businesses that are global in scale, that are high growth, that there’s opportunities for margin expansion, that are platform-based business models, and that are really sticky among their customers.

So, what we saw at Spotify was a company that was able to leverage their access to music, to audio more generally, to a global audience of subscribers that love the platform. And there’s immense growth opportunities within there. I think I’d encourage anyone to listen to the stream event from a couple of months ago that the company put out that really kind of laid out and articulated the vision of true billion-user Spotify ambition, which we think is achievable. And I think that Spotify is one of those companies with a lot of optionality. So, companies that we generally are attracted to are ones that maybe have multiple business lines of revenue generation.

So, the traditional sort of music model that Spotify has leveraged is developing relationships with artists and then, ultimately, being a music-first platform. What the next version of Spotify 2.0, what we view it as becoming is a platform for all audio creation. And so, that’s everything from podcasts to storytelling, and it’s no longer just a music platform, it’s a platform for any sort of audio experience, which as you know very well, is increasingly attractive from an investor perspective, just given frankly, some of the dynamics that we see on these platforms. The ad rates, the retention, the consumer interest. And ultimately, I’d say obviously Spotify has some big competitors: Apple, Amazon, but remains to be the largest platform right now. And we think that there’s immense opportunity left over the next couple of years. It’s a bit of a pivot point for the company, but we love the optionality that they have to expand into something much larger than just music.

What options could become real businesses at Spotify?

[01:06:13] Tilman Versch: What, like looking out five or ten years, what options could become real businesses at Spotify?

[01:06:22] Eric Markowitz: I think, certainly the monetization of these relationships between individual creators and their fans. We’ve seen business models like Patreon really explode over the last few years as a result of this sort of decentralization. So, we are attracted to businesses that enable people to make money.

We have a position in Shopify which again is a platform-based business model that enables transactions between essentially buyer and a seller. We see this with Amazon as well. What Spotify can ultimately do is to be that platform on which those transactions take place.

And that will integrate both direct, likely direct relationships of monetization, but also, great advertising opportunities as well down the road. So really specifically target specific audiences and enable creators basically to create the content that they want to and monetize it really successfully. Certainly, no other company has been able to do that with audio so far, and frankly, Spotify is from our perspective, the most innovative successful disruptor in this arena, and there’s immense runway for growth there.

Why do you prefer Spotify instead of music labels?

[01:07:41] Tilman Versch: Why do you prefer Spotify compared to the labels? Like Universal Music or other labels, Warner Music I think it is.

[01:07:54] Eric Markowitz: I’m sorry. Can you maybe reframe the question a little bit?

[01:07:58] Dan Crowley: Why the music labels?

[01:08:00] Tilman Versch: Yeah. The music labels, like why do you prefer Spotify compared to the labels?

Hey, Tilman here. I’m sure you’re curious about the answer to this question, but this answer is exclusive to the members of my community, Good Investing Plus. Good Investing Plus is a place where we help each other to get better as investors day by day. If you’re an ambitious long-term-oriented investor that likes to share, please apply for Good Investing Plus.

How much self-disruption is embedded in the DNA of Worm Capital?

[01:08:51] Tilman Versch: To sum our interview up, I want to ask the question how much does self-disruption is embedded in the DNA of Worm Capital? So, I think you mentioned at one point that you were kind of Buffett and Munger fans, but you’re always evolving and you have a certain factor of self-disruption, I think, embedded in your company or?

[01:09:12] Eric Markowitz: That’s a great question. And I think that it is something that Arne really preaches pretty religiously, is that we can fall victim to being disrupted ourselves. And so, what that means is yeah, being open-minded to challenge our own perspective, our own views, and frankly just to not have opinions about any investment.

Opinions are not really helpful. In fact, we pride ourselves on constantly challenging our conviction and starting each day with a fresh piece of paper. And I think that over time, this sort of, highly conviction, patient approach maybe can draw you down the path of being kind of stuck in your ways. And we need to constantly fight that to reassess and to challenge our viewpoints, and be flexible when we need to be. So yeah, it’s a great question because we do think about that quite often.

[01:10:23] Dan Crowley: Yeah. And Arne has been at this quite a while and from his perspective, if he’s not getting a little better every year, it’s not worth doing. So, we just, number one is, try to stay humble in all of our opinions and look to the future. And even if we have had a little bit of success, that doesn’t mean anything going forward. So, just try and get better both in our analytical work and our psychological work and all those kinds of things. Just try and keep moving forward and because, people not making mistakes, or really dramatic mistakes is, maybe the key to success. So just try and get a little better all the time.

Is there something you want to add?

[01:11:18] Tilman Versch: For the end of our interview, is there something you want to add we haven’t covered that’s interesting about Warm Capital?

[01:11:28] Eric Markowitz: Not too much.No. I thought maybe the only, kind of thing I’d like to add is, Arne is super competitive, right? And I think you have to be really competitive in this business to stay really focused. And so, while he’s not on this call, I think his message would be that he’s super excited about the next 10 years.

And it’s just a matter of staying focused, staying truly competitive and eager to win, and wanting to attack those opportunities that we spot. Soyeah, no, he, I think, I would just add, maybe that, well, we can end it there. We can cut that out. I don’t really have anything else to say there.

[01:12:08] Tilman Versch: Do you have something to add?

[01:12:13] Dan Crowley: Yeah. Yeah. Maybe. No, just that we’re, we think it’s going to be a really interesting 10 years and that there’s a lot of opportunities. And then the converse to that is that, we’re going to see a lot of change and positioning is super, supercritical, so, yeah, we appreciate the time and the, and thanks.

[01:12:37] Tilman Versch: Thank you very much for coming on and answering these questions so openly and laying out your position and your approach. Thank you very much.

[01:12:45] Eric Markowitz: Thanks Tilman. It was a pleasure

[01:12:47] Tilman Versch: And bye to the audience.

[01:12:49] Eric Markowitz: All right, bye everyone.

Disclaimer

[01:12:53] Tilman Versch: Also here is the disclaimer. You can find the link to the disclaimer below in the show notes.