In July 2021, I did an interview with Fred Liu of Hayden Capital. You can find all content with Fred Liu in our Hayden Capital archive.

- Introduction

- Writing letters & opportunities from the letters

- Benefits from "sharing secrets"

- Subscribe, like & review

- Hayden's edge

- The "Too Hard"-bucket

- Time spent exploring new businesses

- Criteria to invest in a new business

- Consumer addiction

- Indicators for great management

- Steps after the discovery of a great idea

- Qualitative vs quantitative work

- Listening to the street

- Reaching the top 1% of expertise on a business

- The number of great businesses worldwide

- Distinguishing a great from a good portfolio company

- Selling stocks

- Acquiring customers

- Lack of innovative strategies

- Capital allocation

- Thoughts on company culture & working within an industry

- Inflection points on S-Curve

- The confidence to pay up

- Options within Sea Limited

- Sea Limited's competition: Community exclusive

- Thoughts on the regulators

- Factoring in regulation

- Asia tips for Western investors

- Considering risks after a great year

- Finding opportunities

- Goodbye

Introduction

[00:00:00] Tilman Versch: Fred, it’s great to have you back for the second part of our yearly interview. In the first part, you were telling me about the frustration and fire that led to some learnings in your letters, making you want to help people get a better understanding of the investing world we are looking at. How did you observe the impact of your letters? Did they change things, and to what extent did they change things?

Writing letters & opportunities from the letters

[00:00:35] Fred Liu: Maybe it would be helpful to give a little bit of history regarding the letters such as why they first started, and how it’s impacted the way that we do things at Hayden. When I first started Hayden, we really just started with a couple of families around us. Hayden didn’t have a brand, and no one knew who the heck I was. I was really just writing for myself at first and really trying to put my thoughts onto paper.

Probably 95% of them that are not going to be right for us. In terms of building an investment firm and getting what we’re doing out into the world, I thought that writing our letters and just making it public would make us very easy to find. It’s surprisingly something that most investment firms don’t do, but I think it’s one of the best tools that an emerging manager has nowadays. A lot of my inspiration from back in the early days was reading other peoples’ investor letters. The reason why it’s named Hayden capital is because I spent a lot of my freshman year inside of Hayden dorm at NYU reading other investors’ letters. conferences. I got a lot of value out of that and so I always said I’m going to write for myself and put my ideas onto paper. At the same time, they’re going to plant the flag in the ground and allow other people to also learn about what we’re doing and those who resonate can come and find me.

I also recognized that in terms of building an investment management firm, which I mentioned in the last interview, about how we really try to find partners that are very well aligned with us. Most partners out of a pool of a hundred potential people out, there are probably 95% of them that are not going to be right for us. In terms of building an investment firm and getting what we’re doing out into the world, I thought that writing our letters and just making it public would make us very easy to find. It’s surprisingly something that most investment firms don’t do, but I think it’s one of the best tools that an emerging manager has nowadays. A lot of my inspiration from back in the early days was reading other peoples’ investor letters. The reason why it’s named Hayden capital is that I spent a lot of my freshman year inside of Hayden dorm at NYU reading other investors’ letters.

The internet was just starting to come, and people were starting to put their ideas onto the internet. You were starting to get presentations from Ira Sohn or different types of conferences. I got a lot of value out of that and so I always said I’m going to write for myself and put my ideas onto paper. At the same time, they’re going to plant the flag in the ground and allow other people to also learn about what we’re doing and those who resonate can come and find me. There were a couple of other investors who were starting to do that, like John Huber. I remember reading his stuff even before I started Hayden. Hi John, you’re a big inspiration to me! We just really started publishing.

It was probably about two years after we published our first letter and started putting them on the internet before we started getting real traction. As I had more and more people reading them, a lot of people would reach out. I would travel and I would include in our letters what cities I was visiting and tell my readers to let me know if they wanted to grab a coffee. I would have really interesting conversations with my readers. I met a lot of my current network that way. You get differentiated insights where you aggregate all this information together and then you re-distribute it back out into the community through the letters. It creates this virtuous cycle and that’s really what has happened here.

What is also interesting is that because our materials get sent around a bit more widely nowadays, it helps us curate our partner base. Number one, because it reaches the hands in various corners of the world of people who think like us, and they naturally want to engage. They reach out, but also amongst companies too. A lot of companies that we are interested in, or competitors of the companies that we own have started reading our reports. We get feedback that way as well, so it just created this virtuous cycle which is pretty amazing. I honestly don’t think you could have done this as an investment firm 30 years ago or even 20 years ago when the internet was just starting to come about.

I think if you tried to run a hedge fund 20 or 30 years ago in New York, you were probably collecting capital from the same pool of partners. There would probably be 50 or 100 people that would sit within the same circle group, and you would be having dinners with them and meeting them periodically. But, out of those 100 people, probably most of them wouldn’t align with you. If your pool is smaller, you are forced to accept capital that isn’t right for you, so you need to be a little bit more on guard, a little less transparent and a little bit more cautious of how you protect that pool of capital to make sure that your ideas don’t disseminate out and that the churn within your client base is low.

Today, we are able to pick our spots and skim the cream off the top from a global investor base. So, we don’t have those problems and we can be more transparent and more open with our ideas. That creates that virtuous cycle which I think is just amazing. I said in the last interview that I’m still surprised how many investment firms out there are still operating under a model that worked 30 years ago, but probably not today.

Benefits from “sharing secrets”

[00:05:23] Tilman Versch: There’s also a certain surplus to sharing your secrets and insights that others may not have but sometimes you can profit from keeping that inside secret or insight. How are you dealing with this tension?

[00:05:38] Fred Liu: There’s a couple of sources to hedge, informational, analytical and behavioral. With informational sources, the internet is free information. Most data out there, you have access to today as an investor, probably wasn’t available 20 years ago. We operate in businesses that live online. You can literally track GMV, weekly sales, a breakdown of that GMV. You can also track customer breakdowns and geographic concentrations. How could you do this 20 or 30 years ago? All of this information is readily available to most investors today. That is no longer an edge. Your edge is created by collecting all of this available information and filtering it in a way for you to then go have some sort of analytical edge for you to have the insight that other people don’t have.

Your edge is created by collecting all of this available information and filtering it in a way for you to then go have some sort of analytical edge for you to have the insight that other people don’t have.

So, I have no problem disseminating our information out, even if we’re giving a little bit of our secret sauce. Who cares, we’ve already built our position. The more people that know about how great this company is, the better quality the shareholder base is. If we can upgrade that shareholder base in our own little way, that benefits everyone. It benefits the company, it benefits us, it brings more attention to the stock and maybe it pulls forward some of that valuation. So, I honestly think it’s beneficial for everyone here.

Subscribe, like & review

[00:07:06] Tilman Versch: One thing to do that isn’t really a secret. Please subscribe to this channel, leave a like or comment. If you hear the podcast, you can also go to the portal you’re hearing it in and leave a review. This really helps me. Thank you very much.

Hayden’s edge

[00:07:25] Tilman Versch: That’s interesting. Let’s take a step back to boil down to the point of what great businesses are for you, but maybe let’s start with your edge. How do you define your edge as an investor in the field you’re operating in?

[00:07:43] Fred Liu: I think in the last interview, I talked a little bit about how we’ve been narrowing our circle of confidence for the majority of Hayden’s life. We’ve only slowly started expanding it out again. I think our edge is just understanding internet-based, consumer-facing businesses in US and Asi. It’s just where we spend a lot of time where we’ve dug and looked at a lot of companies. It’s not necessarily something I was born with; I just spent a lot of time in this area. We’ve developed a competency that’s really the edge.

All investing is pattern recognition. You need to look at enough data points and patterns to formulate your own idea of what works and what doesn’t and how businesses and ecosystems develop. That just takes a lot of time. Our edge isn’t some natural secret sauce. It’s just that we’ve spent a lot of time in that area.

All investing is pattern recognition. You need to look at enough data points and patterns to formulate your own idea of what works and what doesn’t and how businesses and ecosystems develop. That just takes a lot of time. Our edge isn’t some natural secret sauce. It’s just that we’ve spent a lot of time in that area. That’s really the basis of it.

The “Too Hard”-bucket

[00:08:45] Tilman Versch: Even if you have spent a lot of time in the area of your edge. What are the businesses that fall into your “too hard” bucket, where even in your edge area, it’s too hard to grab?

[00:08:59] Fred Liu: I would say something that is kind of on the periphery, but a little bit more removed from the periphery of our circle. These is probably B2B companies. Whether you want to talk about software or any companies selling to businesses is very tough because on the B2B side, you’re typically concentrated in terms of the number of customers that you have.

Let’s say you’re a soft SaaS type of business, you have 100 customers. How many people inside of each corporation really use your piece of software and are extremely knowledgeable about it? Maybe like five to ten. So, call it a couple of hundred customers in the entire world who probably have the information and data insights that you’re looking for when you’re trying to do research. Then we have to go find a representative sample of these customers. That’s really tough compared to something like e-commerce or a consumer marketplace where there are probably hundreds of thousands or millions of users. It’s a lot easier to go find the customers who have some sort of insight in how they use the product and get can get feedback on it. Then you can build a representative sample a lot easier. So. I would say that anything that’s B2B is a bit more outside of our circle. It’s also hard to collect this information online, whether you’re talking web scraping or all data or what have you. Just because you know a lot of these habits and how they interact with the product just doesn’t live online in the beginning, so it’s hard to track.

[00:10:41] Tilman Versch: Is there another example for the “too hard” bucket that lies within your edge?

[00:10:49] Fred Liu: The obvious ones would be like healthcare or biotech or really anything that lives outside of where we’re spending our time. Like I said, I used to cover industrials in a previous life in a different role. I haven’t done it in eight years and so I would say that even my skillset and patterns are probably outdated by this point. So, if I try to go back to it, it’s probably outside my edge as well.

Time spent exploring new businesses

[00:11:20] Tilman Versch: If you look back over the last 12 months, how much time have you spent on existing portfolio positions and how much time have you spent on new ideas?

[00:11:31] Fred Liu: I would say 60:40. 60% is spent on research and maintenance work and just keeping on top of things. Some of these businesses evolve so rapidly that they’re launching completely new business lines or completely new geographies and a couple years down the line, they may be a completely different business than when you first invested. So, you have to stay on top of it. Then the other 40% is turning over rocks and adding more data points to your pattern recognition framework.

Criteria to invest in a new business

[00:12:14] Tilman Versch: What makes you decide to want to invest more time in a new name and grab the hook that is found there?

[00:12:21] Fred Liu: I would say there’s four main criteria that we’re looking for, although it can be flexible depending on the company. Really what we’re looking for is, number one, a strong industry tailwind. We want a large tailwind propelling this company based on some sort of consumer behavior trend because of some new habit that’s being formed or because of the internet or technology. It’s just a completely brand-new business model that is able to exist that wasn’t previously able to exist but is serving the same need or service that has always been in demand for decades or hundreds of years. So, that’s number one.

Number two is that once you spot this kind of tailwind, or what my friend describes as finding a wave. You’re looking for big waves. You also want to find the companies that are going to be leading the pack because certain companies have certain advantages and in the industries that they operate in, tend to benefit from scale and tend to be in the “winner take most” type of market. So, you want to find the companies that have a certain advantage, culture or secret sauce to them that allows them to be at the forefront. As they pull away from the pack, even more advantages accrue to them, such as more data. For instance, the more transactions you see across different geographies, the more you can tailor your inventory and business model around that. Smaller competitors wouldn’t be able to compete with that.

Also, they may have better access to capital due to being able to list first. Because they have a much stronger shareholder base, their cost of capital is lower so they’re able to experiment more with that lower cost of capital. Some of those experiments are going to work and that’s going to propel them even further ahead of their competitors. So, we’re looking for some aspect of that.

Number three is looking for a great management team that is capable of navigating this. In our industries, they’re evolving so rapidly. You don’t need someone to just maintain the status quo and make sure that the business doesn’t die. You rather need someone to innovate and constantly propel the business forward. In this case, it’s kind of like being a surfer on this wave. You see this big wave, but you also need to have the skills to really surf that wave and hopefully when that wave peters out, to hop onto a new one that is equally as large of a tailwind or as large of a wave.

Then lastly is around valuation. We’re looking for some sort of disconnect in the markets. When we typically initiate a position, they’re not very well known in the market. There’s usually controversy and uncertainty in terms of the trajectory of the business and how steep that future earnings or power slope is going to look in the future.

Then lastly is around valuation. We’re looking for some sort of disconnect in the markets. When we typically initiate a position, they’re not very well known in the market. There’s usually controversy and uncertainty in terms of the trajectory of the business and how steep that future earnings or power slope is going to look in the future. We feel, based upon our data points and pattern recognition that we have a differentiated opinion on that. If we are right, we’re actually going to get multiple expansion over the course of that business. So, we think that earnings are going to cager higher than what the street expects over the next three, five or ten years. On top of that, as the business gets more certain in the business model, it becomes more evident to people that it’s going to actually be able to be profitable sustainably. You’ll see that multiple also expand on top of that earnings cager. So, those are the four things that we’re looking for here.

Consumer addiction

[00:16:12] Tilman Versch: On the leader of pack indicators, you mentioned the cost of capital. What are other indicators that might indicate a company is a leader of its pack?

[00:16:23] Fred Liu: I would actually say that cost the capital is an output rather than an input. It’s not necessarily what we’re looking for. It depends on the industry. Every single business is different in terms of what criteria allows us to predict that they will be the leader of the pack. For instance, with consumer marketplaces, the number one thing you should look for is addiction. We’re looking for consumers and suppliers to be addicted to this platform in some form. I think I understand the basis of the question and where you’re going so maybe I’ll preempt it.

Every single business is different in terms of what criteria allows us to predict that they will be the leader of the pack. For instance, with consumer marketplaces, the number one thing you should look for is addiction. We’re looking for consumers and suppliers to be addicted to this platform in some form.

If you think about consumer marketplaces, the best analogy that I have for it, and I’ve talked about a little bit is that they’re like self-regulated ecosystems. As the company and as the management, you’re almost like God. You are almost like the government in a sense. You are dictating the rules and setting the laws for what happens inside of this ecosystem that you create but you don’t really control the businesses that move to this ecosystem. Let’s say it’s like a new city. You don’t really control the businesses that come to this new city, and you don’t control the population. This guy decides to immigrate from elsewhere to your new city but you’re setting the rules and making things attractive enough for these businesses and these consumers to then interact with each other. So, whether it’s informal taxes or zero taxes, that’s always great for attracting new people to your new city. Then hopefully they start interacting with each other. People love living there and get a lot more value living there than the cities where they came from and so they aren’t going to move. You can charge them a two or five percent tax but say they get ten or twenty percent more value than the old city where they came from. They still aren’t going to move and they’re going to be happily willing to pay that tax. You’re going to spend that tax revenue creating even a better environment in your city, whether it’s building or upgrading your subway system or building new roads or widening existing roads. You would be attracting even better talent to your city, so that these businesses have great employees to go work for them. These are typically the early signs that we’re looking, even when a city isn’t charging any sort of tax or in the case of a business, any sort of revenue. You can see that the businesses that move there love it and you can see that the inhabitants that move, there love it. They’re interacting with each other, and a lot of transactions are flowing. That’s the basis of an early sign for a consumer marketplace that is what you should look for because that taxation is inevitable because you’re going to have the ability to tax them, and you will. You will recycle that tax revenue to create an even better city which then creates that virtuous cycle effect.

[00:19:13] Tilman Versch: But then, is it really addiction or is it the love of the offer you give to the customers?

[00:19:21] Fred Liu: I didn’t really touch upon the addiction part, but in the consumer marketplace, it would be transaction frequency. For most marketplaces, we’re looking for people to log on to the app several times a day. For some of our companies, people are spending close to an hour per day inside of the app. They’re ordering and actually transacting four to five times a month. That’s addiction, especially when you compare it to other e-commerce sites where you may get one order every three or six months and you have to remind people that your business even exists when they are searching for a product that your business might be able to serve. I think that’s the real difference. For other business models outside of consumer marketplaces, the form of addiction may be different.

Indicators for great management

[00:20:11] Tilman Versch: You mentioned great management teams. What is a great management team or what are indicators for a great management team?

[00:20:21] Fred Liu: There’s no one-size-fits-all because each business is different, each business model is different. It requires different skill sets. I would say the commonality is that you want to put yourself in management’s shoes. So, when we look at stock we think past, present and future. Each stock is a story.

There’s no one-size-fits-all because each business is different, each business model is different. It requires different skill sets. I would say the commonality is that you want to put yourself in management’s shoes. So, when we look at the stock we think past, present and future. Each stock is a story.

You want to start with the founding. You want to ask yourself why this business was founded in the first place and what problem were they trying to solve. What value were they trying to create? From the time that they were founded to today, what are the key questions or key friction points that they really had to solve to propel them to where they are today. The only reason we would be interested is that they have something special. So how did they create that special sauce in the preceding five and 10 years and hopefully most of our companies are founder-led, so it’s the same people who started on day one to today. What decisions did they make and looking in hindsight, with the data that you have now, did they make the correct decisions? Even if they made a mistake and made incorrect decisions, given the data that they had at that point in time, say five years ago, did they make the correct decisions with that set of data they had? That’s what we’re looking for you.

You have to, number one, know the company well enough for yourself to have an objective opinion of what was the correct decision and what you would have done as an investor.

You have to, number one, know the company well enough for yourself to have an objective opinion of what was the correct decision and what you would have done as an investor. Then you want to go back and see if management thought similarly to how you would have acted. Then going forward, over the next five years, there are generally one to three different questions or friction points that they need to solve to create a lot of value for this business. You want to see how they are thinking about those questions and as an investor, you probably have an objective opinion of what you would do as a management team. You want to see if the management team aligns and has publicly said this is the direction that they’re moving in. Whether you agree or disagree with them, and sometimes you may disagree, but we want to ask then what information does the management team have that we don’t have access to, that if we had access to that data maybe we would change our opinion.

It’s just a conversation and making an opinion or judgment on whether this management team has navigated the corners well over the past five to ten years.

Steps after the discovery of a great idea

[00:22:51] Tilman Versch: What’s your strategy when you have decided to invest time in a new name? Are you going all in, or do you have threats and new ideas Fridays or is Phillip doing all the work? What is your strategy there?

[00:23:06] Fred Liu: Well, it’s a little bit different with Phillip on board over the last couple months, but I would say the process is generally pretty similar. Like I said, each stock is a story. We want to understand the past first. Generally, that is going to take a couple weeks to about a month, on and off, to get your head around it and a lot of that is qualitative. Going back and reading old transcripts and going through different earnings reports, understanding the founding story of this business and the history behind it. Once you understand that, then you should have a firm enough grasp of what the key questions are going forward over the next three to five years. So, at that point in time, we’ll write an initial memo of a couple of pages.

Phillip has been producing like 10-page initial memos, so it could be up to 10 pages. We really want to understand the history, how the business is advantaged today, why we think it’s going to continue to be advantaged in the future and what are the one to three key things that they have to get right for this stock to work.

We’re not trying to answer those questions at that point in time. We’re just trying to lay out the thesis and if this happens the stock is going to be a home run. Then we are also trying to answer these questions. We need to consider what pieces of data, who we need to talk to, what data sets we need to buy or what alternative data providers we need to be able to answer this right. That’s the initial memo.

If we decide to move forward on it, we’re going to build a model at that point in time. A model is really a scrap sheet of paper for you to quantitatively put your thoughts on the paper. You’re never going to out-model someone and be able to get an edge, but it’s good to be able to put hard numbers onto a scrap sheet of paper while you’re doing the future analysis. Then over the next couple of months, it’s really around answering those key questions right and that’s where the fun work starts.

If we decide to move forward on it, we’re going to build a model at that point in time. A model is really a scrap sheet of paper for you to quantitatively put your thoughts on the paper. You’re never going to out-model someone and be able to get an edge, but it’s good to be able to put hard numbers onto a scrap sheet of paper while you’re doing the future analysis. Then over the next couple of months, it’s really around answering those key questions right and that’s where the fun work starts. So, that’s where the primary research takes place. Whether that’s having conversations with people within our network, using certain expert networks, piecing together what competitors are doing and saying, and just understanding how this whole industry is going to evolve over the next five to ten years. Hopefully, by the end of that process, we’ll have a pretty good thesis or understanding of how those couple questions are going to be answered and if it’s beneficial for the company. If it is, and we think this company has a right to win, at that point we’re going to take an initial position in the company. However, our positions are also sized smaller, call it five percent or so, when we initially invest because those questions are really execution-based. They’re based upon how consumer behavior is going to shift, how a certain country’s disposable income may go up. A certain portion of that disposable income goes to a certain type of company, whether it’s e-commerce or what have you, so you have to wait and see if your thesis around that is correct.

As we start to see these KPIs or data points that prove our thesis, that’s when we increase our position over time. While that’s occurring, you have to stay on top of your names, you have to do as much, if not double the amount of work as our initial work during that maintenance phase because we need to monitor our companies very closely and see if that form of addiction actually is taking place. That process can take a couple of months up to a couple of years. As these different KPIs hit, you’re basically flexing up your position. You’re increasing the amount that you’re contributing capital to this position because the business model has de-risked as some of that uncertainty has dissipated.

So, number one, that position probably deserves to be a larger portion of the portfolio because it’s more certain and also your thesis is proven so your future trajectory of this company is probably steeper. The earnings power curve is probably steeper than what the rest of the street expects and so it deserves to gain more capital as well. That process takes you to know a couple of months to a couple of years.

So, number one, that position probably deserves to be a larger portion of the portfolio because it’s more certain and also your thesis is proven so your future trajectory of this company is probably steeper. The earnings power curve is probably steeper than what the rest of the street expects and so it deserves to gain more capital as well. That process takes you know a couple months to a couple years.

Generally, we will stop building the position when they hit right before that breakeven sustainable type of level. That happens usually within the first three years on investments and hopefully, by that point in time, we will have built a position to about our limit, which is 15%. Then once they hit that sustainable type of level, hopefully, we are very confident in that industry tailwind, their management team, that the company is the leader of the pack and will continue to lead the pack going forward. So, because of that, we’re very comfortable with such a large position size. It’s kind of inevitable by that point in time and then we are just going to allow our capital to compound alongside of this business as they create more value for their ecosystem and their stakeholders for hopefully over the next 10 years plus. We just let it live on within our portfolio and produce returns for our partners at that point.

Qualitative vs quantitative work

[00:28:46] Tilman Versch: How much of this work is quantitative and how much is qualitative? It seems like you have a high degree of qualitative work.

[00:29:05] Fred Liu: Yeah, it can be qualitative too. let’s say you have a conversation with someone. We actually just had a conversation with a company that we’re not really interested in, but it was an interesting insight. The person was talking about how much trouble that business is having with monetizing their payments method. This is probably something that most investors don’t quite understand. They don’t quite understand the degree to which it’s tough to monetize this certain business. Because of that, when we build our models, we may have lower expectations for this certain business segment than most compared to the rest of the street. So, that is a qualitative conversation that led to a quantitative insight. I think it’s a combination of both there.

Listening to the street

[00:29:56] Tilman Versch: You mentioned the street quite often. How large a role does the street play in your assessment and how much do you give to the opinion of the street?

Discover the Plus Investing community 👋🏻

Hey there!

Discover my Plus community! The community is great for passionate, professional investors.

Here, you can meet investors, share ideas, and join in-person events. We also support you in starting and scaling your fund.

[00:30:13] Fred Liu: I would say not very much per se. I’ll caveat that within the very short term most people are trying to predict you know on a quarterly basis or over the next year. We honestly don’t care. That’s not what we’re trying to look for. We’re trying to see what do most people expect for the trajectory of a company, whether that’s earning power or market share. We’re trying to figure out what is the general expectation among most investors out there and that general expectation is probably priced into the stock somehow.

We’re hoping to have a differing data insight. For instance, that a tailwind is going to be larger in our opinion than most other investors expect or maybe there is a number two player within their industry that we think has a right to win and become number one within their industry, but most other investors don’t and so that’s probably priced into stock as well. So, we’re trying to look for differentiation in that sense and we’re trying to compare to what other investors are expecting because it’s probably priced into the stock, and we do want that kind of multiple expansion as our thesis is proven right. On a shorter-term basis, it really doesn’t matter for us.

So, we’re trying to look for differentiation in that sense and we’re trying to compare to what other investors are expecting because it’s probably priced into the stock, and we do want that kind of multiple expansion as our thesis is proven right. On a shorter-term basis, it really doesn’t matter for us.

Reaching the top 1% of expertise on a business

[00:31:35] Tilman Versch: You want to reach the top 1% of the investors that have expertise on the company you’re invested in. When do you feel you have reached this top 1%?

[00:31:43] Fred Liu: There’s no way to quantitatively prove that. I just think if you’re having conversations with other investors who own the stock, and through those conversations, you just naturally feel like you have more information or that you have some sort of insight that the other investors haven’t thought about, I would say that would place you among the top of the pack.

Given our concentrated nature, we probably spend a lot more time than most other funds on each name. I know several funds that my friends work at where they may spend a couple of weeks on a name and honestly in this industry that might be a lot but for us, we’re spending months in the initial phase. Just to establish that initial five percent position and then after that we’re doing it multiples of the maintenance work over the next several years. So, just through that nature of time spent, you’re probably going to have more information than other people out there.

I know several funds that my friends work at where they may spend a couple of weeks on a name and honestly in this industry that might be a lot but for us, we’re spending months in the initial phase. Just to establish that initial five percent position and then after that we’re doing it multiples of the maintenance work over the next several years. So, just through that nature of time spent, you’re probably going to have more information than other people out there.

The number of great businesses worldwide

[00:32:41] Tilman Versch: You’re looking for great businesses. Let’s take a general look. I know it’s hard to answer this question but how many businesses do you think exist globally that are great businesses that are publicly investable?

[00:33:05] Fred Liu: Out of the entire universe of companies out there, a small percentage of one, two, or three is my guess. There’s no way to quantitatively prove that. Everyone’s view of quality is subjective. I recently read Josh Tarasoff’s essay where he talks about that exact aspect. When you see a great business you recognize quality, but it’s hard to quantify it. I would say probably a couple of percent. If I were to randomly pick companies out of the indices, I would probably find two or three out of 100.

When you see a great business you recognize quality, but it’s hard to quantify it. I would say probably a couple of percent. If I were to randomly pick companies out of the indices, I would probably find two or three out of 100.

Distinguishing a great from a good portfolio company

[00:33:45] Tilman Versch: Where do you see the main difference in your edge between a good business and a great business in terms of identifying between the two?

[00:33:50] Fred Liu: I would say that’s actually relatively hard. I would say the easier way to identify that is, number one, you want them to be the best within their industry. So, that’s a comparative analysis and then the other question is the leader within a certain industry versus the leader in another industry. Where do you want to allocate your capital? That’s also a bit harder but the best way to do it is just instead of trying to find the absolute best, just try to upgrade the quality of your portfolio consistently. So, try to find the best within the number of rocks that you have turned over. That’s really what we’re trying to do when we come across a new idea, and we think there’s something special about the company. We compare it versus the worst name in our current portfolio. Is it better than this? Do the risk-reward dynamics actually favor this new company? Is there enough return potential in this new idea compared to our existing portfolio company for us to justify the upgrade of that swap. That’s what we’re trying to do.

If you spent all your time searching for the absolute best 10 companies in this world, that would be a really tough process and you would probably be sitting in cash the entire time because it would take a long time for you to go find those 10 companies. All we’re trying to do is just constantly upgrade the quality of our portfolio.

I think if you spent all your time searching for the absolute best 10 companies in this world, that would be a really tough process and you would probably be sitting in cash the entire time because it would take a long time for you to go find those 10 companies. All we’re trying to do is just constantly upgrade the quality of our portfolio. We’re seven years in, and I think we’re at a pretty good place and originally our bar that we needed to beat was cash.

We started with over 60% cash. We took a number of years to get down to low single digits and now our competition is really the worst position in our portfolio. I think that’s an easier way to think about upgrading and comparing good versus great. Then when trying to find the absolute great companies in the world.

[00:35:54] Tilman Versch: How do you create this ranking of your portfolio companies? How do you clarify what companies are the worst and what are the better ones?

[00:36:02] Fred Liu: I think that’s subjective. Number one, some of our companies just can’t absorb that much of our capital or they don’t deserve that much of our capital because they’re still at an early stage. They’re still hypotheses. We still need to see consumer behavior and certain industry dynamics hit. They haven’t yet and so contributing more capital to these positions is not a very prudent thing to do. So, you know it’s not necessarily the companies with the highest return potential that are going to be our largest companies, because our highest potential return companies may also have the most risk associated with them. You have to constantly balance all of these factors. You also have to think about what the likelihood is of a certain company hitting upon these thesis points that you’re looking for versus say your top position may be a more mature company and things are already proven. The management team has already battled tested. They’ve already proven their executional capabilities. You’ve already done hundreds of hours or maybe even thousand hours of work on the name and got to know every single person, so you’re extremely confident in it versus your smaller and less certain position. So, it’s constantly ranking between those. It’s not a hard science. A lot of this is subjective but that’s the role of a good portfolio manager. This isn’t an exact science to this industry.

Selling stocks

[00:37:40] Tilman Versch: How many companies did you say have be removed from the portfolio after the seven years you’ve invested in them? I think one example is Zooplus. Another one is Amazon.

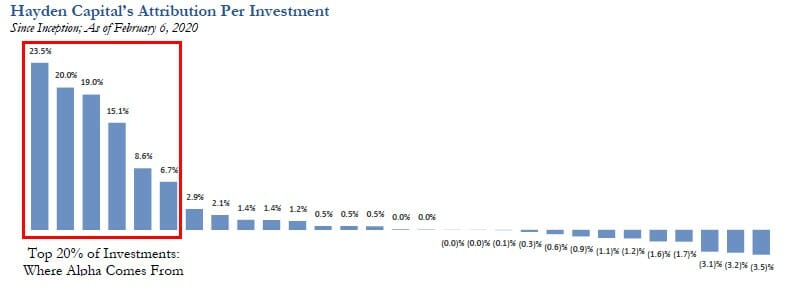

[00:37:53] Fred Liu: We had a lot more churn in the early years of Hayden. If you look at all the positions that we’ve invested in since inception, it’s well over 30. We gave that analysis about a year and a half ago I think in our Q4 19 letter, just about the attribution and hit rate versus slugging rate within our portfolio. It was always the top 20% of our positions that drove the majority of our alpha and today that has gotten even more skewed. We’ve had a lot of names that we’ve basically had to kick out. We own seven today but over the course of our history we’ve owned 30 plus. You can do the math in terms of how many I’ve exited.

We gave that analysis about a year and a half ago I think in our Q4 19 letter, just about the attribution and hit rate versus slugging rate within our portfolio. It was always the top 20% of our positions that drove the majority of our alpha and today that has gotten even more skewed.

Acquiring customers

[00:38:35] Tilman Versch: If you’re in your framework and also talking about addiction, one important part to get people addicted is the consumer acquisition. What do you think is a great strategy for consumer acquisition? For the companies you’re looking at, how much of a role does the consumer acquisition strategies play for you in your analysis to find a great company?

[00:39:01] Fred Liu: How each company acquires customers is going to be different. Let’s consider e-commerce. That’s kind of our sweet spot. So, if you are a lower frequency type of e-commerce platform that’s totally okay. You may be selling very expensive products that people purchase very infrequently, whether that’s like white label appliances right or like electronics or what have you. You can make decent money off that, but the problem is people are not looking for that every single day. They’re looking for it every six months or once a year. So, you probably have to do performance-based marketing or advertising. You have to do Google AdWords to capture them when the consumer has intent to go purchase a new refrigerator or a new laptop. That’s fine, but that customer acquisition cost is variable. Every time you sell something, you’re probably spending something to acquire that customer versus a generalized marketplace that has high addiction that you know people buy four to five times a month that lives on an app button on the home screen of your phone.

You open your phone about 10 or 20 times a day. It’s like prime real estate. You’re looking at that app every single day, every single time you open the phone and maybe a certain percentage of the time, you’re opening it you browse through it. It’s a fun experience. It’s like walking into a mall. I think about them like walking into a mall. You walk into it five times a day maybe, you don’t find something 90% of the time but maybe you come across a shop that seems interesting and has some cool item that you didn’t know you needed. You go explore it and you end up buying once a week.

Those consumer acquisition costs then get amortized over the lifetime of that customer and over the lifetime of those purchases. You’re buying five times a month which means you’re buying 60 times a year. It’s amortized over 60 times and because of that and competition, consumer acquisition costs steadily having gone up in the last couple of years. So, it’s gotten more and more expensive to acquire customers. In China now, it costs about 20 to 30 USD to go acquire a customer and that’s why you have this consolidation of these large platforms that are then trying to sell many items because they need to amortize that high CAC.

So, it really depends. To answer your question, it really depends on the business in terms of what makes a good consumer acquisition type of strategy, but I would say the better model is probably the ones that have very high addiction and very high repeat type of customer base because you can amortize that CAC over a very long period of time and when you break it down on a per transaction basis, that means it’s probably in a 1.5USD sometimes. This means that you can also lower your basket sizes, the number of items that consumers need to purchase every single time. When you lower your basket sizes, you increase immediate gratification. That kind of dopamine effect of immediately being able to buy something and having it arrive sometimes on the same day to your door. Then you do it more and more and it creates that virtuous cycle so it depends on the company, but I would say the addiction, high repeat rate type of businesses is more attractive.

The better model is probably the ones that have very high addiction and very high repeat type of customer base because you can amortize that CAC over a very long period of time and when you break it down on a per transaction basis, that means it’s probably in a 1.5USD sometimes. This means that you can also lower your basket sizes, the number of items that consumers need to purchase every single time. When you lower your basket sizes, you increase immediate gratification. That kind of dopamine effect of immediately being able to buy something and having it arrive sometimes on the same day to your door. Then you do it more and more and it creates that virtuous cycle so it depends on the company, but I would say the addiction, high repeat rate type of businesses is more attractive.

Lack of innovative strategies

[00:42:25] Tilman Versch: Are there any good examples you can see that have great customer acquisition strategies? You did this with your letters, where you had your own network acquisition strategy. Creating your letters was very cheap and a great idea.

[00:39:01] Fred Liu: Not that I can think of. I don’t think there’s anything brand new out there that companies are doing. Word of mouth is obviously the cheapest by far. Some companies give referral codes for instance. When your family and you are trying to build trust in terms of a new way of buying something, hearing it from people that you already trust, family and friends, is one of the best ways to go acquire a customer. I already trust my friend. My friend says this platform is great and it’s the cheapest and high-quality products. I’m probably going to have a much higher chance of using that service. I think that’s probably the best, but I don’t think there’s really anything brand new out there in terms of that.

Capital allocation

[00:43:41] Tilman Versch: How do you make sure that the capital allocation of the company you’re investing in is great?

[00:43:49] Fred Liu: I’ve given this chart in my materials for the last couple years in terms of how everyone is allocating capital. In some sense, if you think about our partners, our LPs are really choosing between manager a, b, c or d. Why are they choosing Hayden and how do they build trust that Hayden has the best capital allocation opportunities? They’re diving into our portfolio and asking questions like why did you chose stock A versus stock B versus stock C.

First, they need to underwrite the pool in which we’re operating in. Does this pool of ideas, whether it’s consumer tech in the US or Asia, have attractive returns in the first place? Then among that we are the fishermen fishing in this pool. Are you able to fish the highest return? That process is a judgment of our investment process and so you dive into specific names and when we’re looking at companies, these managers are also allocating capital themselves. They’re allocating into project A, B and C. Maybe they’re building a new factory or choosing to spend a couple hundred million bucks on acquiring new customers or launching a completely brand-new product that has no relation to their current core business. Which one is management choosing and why?

As an investor you need to have enough data yourself and enough of an opinion to then go and say I think they should have chosen project A.

As an investor you need to have enough data yourself and enough of an opinion to then go and say I think they should have chosen project A. I think it’s the highest return type of project based upon my unit economic analysis, conversations I’ve had and on my understanding of where this industry is going. The project they should have chosen was A, but management chose B. So why did they choose B? Then you have that conversation to try to understand why they went in that direction, and this goes back to what I was saying earlier. Maybe they have other data or something else that they’re seeing that you, as an investor, are not. So, maybe we are wrong. We want to understand that decision-making process and the “why” behind it and so at that point it’s like you’re trying to determine if you are right or if management is right. You make a judgment on that and if sometimes management makes the decision that you thought they should have made then that’s easier, but you could both be wrong at the end of the day. Maybe that that’s how you determine if they’re a good capital allocator. You just need to understand the “why” behind it and make that subjective opinion based upon the quantity and bulk of work that you have done up front to reach that conclusion.

You just need to understand the “why” behind it and make that subjective opinion based upon the quantity and bulk of work that you have done up front to reach that conclusion.

Thoughts on company culture & working within an industry

[00:46:37] Tilman Versch: What, in your opinion, makes for a great company culture?

[00:46:40] Fred Liu: Again, that depends. There’s no one size fits all. If you are a company that is based upon, let’s say efficiency. For instance, JD has always been known to have a top-down military-esque type of culture. Decisions are made at the top and then everyone else at the bottom kind of executes the orders and follows them, but just at a rapid and efficient pace. So, their model has always been logistics for instance. That doesn’t require necessarily innovation from very low-level employees. That just means getting it to the customer’s door in two hours and doing it in a very efficient and cheap manner. That may be their edge and that may be the culture a military-esque style execution, or it may be more based upon innovation. You need your middle level employees and your junior level employees to constantly be generating new ideas and innovative ways to execute this new business line or this new strategy.

You need a very open-minded management who enables their lower-level employees to go run with those ideas and test if they work in the experiment. That’s a completely different culture. It really depends on the type of company that you’re investing in right.

[00:48:06] Tilman Versch: So, the quintessence of the great businesses. Do you always have to analyze them in relation to other businesses in the space they are operating in or in the industry they’re operating in?

[00:48:19] Fred Liu: I would say you have to figure out and determine what is their competitive advantage, what is their edge, why is a company going to be the leader in this industry, what do they need to do to be the leader, what do customers care about, what do their suppliers care about and how do you go execute upon that. Once you know how to answer those questions, then the next question is, does the culture of this company then enable and maximize their ability to do that. Each company is different, and each industry is different. So, it depends.

Inflection points on S-Curve

[00:49:00] Tilman Versch: I have some questions coming up on the S-curve and inflection points related to it. What are examples of inflection points you observed in some of your early bets that convinced you to average up?

[00:49:19] Fred Liu: The best example is, let’s say C, because we were just talking about consumer ecosystems, and we were looking for addiction. Before we even invested, we knew that Shopee, the platform, had higher addiction because people were transacting on the platform four to five times a month. People were visiting the app more frequently; people were spending more time inside of the app. Anyone who’s interested can go back and look at our 2018 presentation where we laid out these KPIs. At the point at which I gave that presentation, our position was still very small. It was lower than five percent. So, we knew there was addiction. We knew that they had basically built the infrastructure for this brand-new city that they were creating. They were inviting businesses to come live in this new city by offering zero taxes, basically zero commissions and they were inviting inhabitants to come live in the city, the demand side, by basically giving away free money. They were saying zero shipping costs, zero commissions. We’ll even give you promo codes 30% off, 20% off, what have you if you make one

Purchase. So, they were basically paying people to come live in the city but what we were saying was that once they moved there, they were transacting four to five times a month. They were spending a lot of time inside of these shops. They were providing more reviews for each individual shop owner than where they were listed elsewhere. That means from a shop owner perspective, you’re probably not going to move to a different platform because this is where the bulk of your orders are coming from.

This is a very labor-intensive process because if you understand e-commerce in southeast Asia or just Asia in general, a lot of it is chat based. People ask a lot of questions, so you have to spend a lot of time answering questions. This is where most of the time was spent but there was no monetization, there was no revenues and there was no tax revenue coming in, but you knew that the company’s game plan and their strategy was that once you get people addicted, they are then going to charge a tax. They made that extremely clear.

We also knew through some of the sales materials that we were able to get a hold of hold of that they were communicating to their merchants that they were going to raise their taxes on them very soon. They told them get their products on. So, we have this already addictive kind of foundation to this ecosystem, and we knew that they were going to charge say 1% tax. A 1% tax really isn’t very much if you are providing your sellers with 90% of their business. You’re going to happily be willing to pay for it and they’re selling products where their margins are close to 50%. They will happily pay for that 1%.

So, were’s a very vibrant sticky ecosystem going on here and so over the following six months we again we had a very small position up front, but we increased our capital committed to that idea because our thesis started to prove itself out. Over the following year, they continued to raise their prices and diversify their base of sellers and the type of products that sold. They started moving up-market into more branded items as opposed to unbranded items and you started seeing people buying very expensive items like Dyson vacuums. They were able to do so because they had built so much trust. So, every step along the journey as they moved upmarket, as they built their logistics, as their shipping times decreased, as they built more trust with consumers and as consumers spent more and more time inside of the app, we continued to increase our position over that period.

So, we invested right before that monetization phase and that was what gave us an early indication that something might work as soon as they raised the monetization over the next six months. We basically saw, number one, none of the sellers left and none of the customers left. In fact, this platform continued to grow above their competitors that were still giving away free money. Actually, what we saw was some of their competitors followed suit in terms of raising prices and raising their taxes. That proved to us that there’s something going on here. There’s a very vibrant sticky ecosystem going on here and so over the following six months we again we had a very small position up front, but we increased our capital committed to that idea because our thesis started to prove itself out. Over the following year, they continued to raise their prices and diversify their base of sellers and the type of products that sold. They started moving up-market into more branded items as opposed to unbranded items and you started seeing people buying very expensive items like Dyson vacuums. They were able to do so because they had built so much trust. So, every step along the journey as they moved upmarket, as they built their logistics, as their shipping times decreased, as they built more trust with consumers and as consumers spent more and more time inside of the app, we continued to increase our position over that period. That’s a relatively newer investment for us. A call like three years or less, but I think it’s a good example of our process for building these positions.

[00:53:52] Tilman Versch: You started your position with a 2 – 3% tracking position, am I right?

[00:53:57] Fred Liu: Yeah, it was a couple percent by the time I gave that presentation. If I remember correctly, it was about a 4% position there and then by the following spring, we increased it to about 8 – 9% and the stock had also moved as well. It went from call like it 10 bucks to 20 bucks or so. We also contributed more capital.

The confidence to pay up

[00:54:19] Tilman Versch: How much are you willing to pay-up over time if you get more confident in your investment?

[00:54:26] Fred Liu: It depends on how confident we are and the difference between the slope of that earnings curve that we expect versus what’s already priced into the stock. If we are extremely confident for instance that this company is going to realize 50% IRRs over the next three years, but the stock is pricing in 20% type of expectations, we’re going to be able to pay-up for it because we’re extremely confident. You know we have some sort of differentiation versus what’s being priced into the name, so I wouldn’t necessarily say that’s paying up. In that case it’s just we have a different view of what the future earnings trajectory looks like versus everyone else, and we think we’re paying a pretty fair price, not an expensive price or even a cheap price. I wouldn’t say that we really pay up for our names.

[00:55:25] Tilman Versch: If the multiple goes up, aren’t you paying up then? How do you see this?

[00:54:26] Fred Liu: You mean as we hold a name and the multiple goes up and we continue to hold it, is that what you’re saying?

[00:55:25] Tilman Versch: No, like when you bought Sea three times, as you just described it and I think the multiple might have gone up during this time or didn’t it go up?

[00:55:54] Fred Liu: It has. I mean it’s gone from extremely cheap, almost like a deep value type of situation that was not pricing in the Shopee e-commerce business at all to a point where it’s being priced but not at anything that’s very taxing on the stock. We’re looking for a close to 10 billion dollars in revenue this year. If we count gaming revenues as bookings not reported revenues but they’re going to do about 10 billion, and on that gaming, they realize let’s say a blend of e-commerce and gaming. They’re going to realize close to 50% type of margins. With gaming, they’re doing about 60 and e-commerce is about 40 structurally. So, we’re looking for 4-5 billion dollars in profits for a company growing 80 – 90%. It’s trading at around 140, 14 times. That’s not extremely taxing for how dominant this business and how many free options are embedded into this business. Just on the core business that we have extremely high confidence in, we still expect it to grow between 60 – 80% over the next year or so and that’s going to very slowly decline to a more normalized rate.

So, that’s why we have such a large position and why we’re extremely confident. I don’t think that valuation is very taxing at all. We’re actually not expecting multiple compression in this case from here until maturity, but if we had a name that’s say trading at 30x and we think that at maturity, because of competition or whatever other factor, that it should be trading closer to 10x at maturity, we better be very confident in that earnings trajectory. It’s always your headwind that is going to be that multiple compression. Your tailwind is going to be that earnings growth, the net of that is your stock’s return. So, you just better be very confident on that earnings trajectory and that’s going to be a very volatile situation because it’s constantly going to be a tug of war between that earnings growth and that multiple fluctuation. We try to generally avoid those situations. If the net of those starts getting close to say between 10% and 15%, that’s generally when we’re going to start trimming, and if it falls below 10%, which is generally where I view the markets or the S&P type of opportunity cost. We’re probably going to sell out at that position and just follow it and wait for a better entry price tore-go into it. It’s really about the net of those two, the headwind and the tailwind. Usually when we enter a name, we expect multiple expansion and we also expect that earnings CAGR to continue to compound at very attractive rates.

We try to generally avoid those situations. If the net of those starts getting close to say between 10% and 15%, that’s generally when we’re going to start trimming, and if it falls below 10%, which is generally where I view the markets or the S&P type of opportunity cost. We’re probably going to sell out at that position and just follow it and wait for a better entry price tore-go into it. It’s really about the net of those two, the headwind and the tailwind. Usually when we enter a name, we expect multiple expansion and we also expect that earnings CAGR to continue to compound at very attractive rates.

Options within Sea Limited

[00:58:42] Tilman Versch: What are these three options you mentioned within Sea?

[00:58:46] Fred Liu: Payments, Sea money which is an e-wallet in Indonesia and they’re expanding into Malaysia. They have Shopee Food for instance. They are starting to compete with Gojek and Grab on the food side really to kind of funnel into their payments business. They’re going into LATAM for instance which we’ve talked about previously. They have a couple games in the pipeline. You don’t really know if they’re going to work until it actually launches and see what the reaction is from the gamer base. There are a couple options that really aren’t being priced into the stock.

Sea Limited’s competition: Community exclusive

[00:59:24] Tilman Versch: How are you tracking the increasing competition to ensure that more capital goes to Grab or other local champions like Coupang and JD. How do you keep track of these developments and evaluate them?

Follow us

Thoughts on the regulators

[01:00:30] Tilman Versch: We haven’t covered one important aspect, the regulator. Because you have different regulations and regimes in which Sea is operating and we also see it with China at the moment, local data sovereignty requirements and topic. How do you factor in the regulator in all these markets?

[00:01:53] Fred Liu: I’m never going to have that edge. In southeast Asia for instance, a lot of these countries recognize that tech companies and technology is basically going to be a source of their growth and GDP. It’s serving their consumers in terms of allowing access to products that maybe are not available to them locally. It provides a more frictionless experience that allows them to upgrade their consumption and their lifestyles. So, that is great. In terms of the employee base or in a labor market, all these countries want to create higher quality workers. They want to create tech employees to upgrade the number of incomes that they can command as a country and tech companies allow them to do that. When you look at kind of the top companies in Indonesia, a lot of these guys have very close government connections. Some government officials may sit on the board. They may be former government officials and so there are different connections that smooth the process.

At Sea for instance, Forest always credits the EDB program for jump starting and providing some capital to Garena back in the early days. They hosted the former meetings inside of Shopee headquarters. You can tell that there’s very close ties with the Singapore government. You can go on LinkedIn, and you’ll see posting all the time saying that they’ve just hosted foreign ministers of whatever country so you can tell that they’re pushing in that direction. I’m never going to have an edge in terms of that and have any sort of secret info that’s going to give us some sort of extra alpha. That’s not something that I do but you want to know that at least the company is thinking in that direction and is making a conscious effort towards cultivating these regulators.

Factoring in regulation

[01:03:04] Tilman Versch: Are you factoring regulatory or political risk in your valuation of companies. For instance, if you’re still invested in JD, does that play a role for you?

[01:03:21] Fred Liu: It depends where the company sits relative to what regulators ultimately want. I would say with China in general, I mean you’ve seen the news in the last six months or so, it’s definitely become a bit tougher. There’s more uncertainty. There are some companies that have gotten unfairly punished that really have no effect from all this regulation because they are actually acting in the interest of the government and where the direction that the government wants to push society to go. As investors. especially for a lot of these companies that are listed in the west, western investors don’t necessarily understand that or don’t see it so they kind of punish all stocks indiscriminately.

In South East Asia, it’s a little bit different because these companies are very large. They are on the side of the government and pushing these countries, societies and populations in the direction that the governments want them to go. They are not butting heads and creating conflict and because of that, there’s a lot less regulatory uncertainty in South East Asia than elsewhere.

In South East Asia, it’s a little bit different because these companies are very large. They are on the side of the government and pushing these countries, societies and populations in the direction that the governments want them to go. They are not butting heads and creating conflict and because of that, there’s a lot less regulatory uncertainty in South East Asia than elsewhere.

In addition to, because each individual country is relatively smaller compared to China, each individual market is less important to a company like Sea than say China is to Alibaba. You lose China, you kind of lose all of Alibaba’s business. For Sea you lose say the Philippines, it’s not a huge part of their business. So, you cut off one lake and you still have a bunch of other lakes that you can kind of stand upon and so because of that, the companies that operate in southeast Asia have a bit more leverage, especially the larger ones and the world-class ones, over the government regulators than in other larger markets.

Asia tips for Western investors

[01:05:05] Tilman Versch: Is there anything you want to add about the understanding we need to have as western investors about southeast Asia that we still get wrong?

I would just say open-mindedness. Understand that there are very interesting things that are happening outside of the western world and the US is not the leader in every single aspect of business model development or strategy. There are very interesting new innovations that are happening elsewhere usually tailored for local markets but are probably applicable to larger markets or western markets like the US that you can learn from.

[01:05:17] Fred Liu: I would just say open-mindedness. Understand that there are very interesting things that are happening outside of the western world and the US is not the leader in every single aspect of business model development or strategy. There are very interesting new innovations that are happening elsewhere usually tailored for local markets but are probably applicable to larger markets or western markets like the US that you can learn from. Often by tailoring to local taste or local consumer behavior that can provide a bigger edge than any amount of capital can. You can look at the debate several years ago between Lazada and Sea. Lazada had a lot more capital behind it, but Sea won. That was because they tailored to the local markets versus Lazada that was a very Chinese company that imposed their culture upon the rest of the region. I would just say open-mindedness and to realize that because the world is becoming more and more global, great and innovative ideas can come from a lot of places and sometimes the most innovative businesses don’t sit in the US.

I would just say open-mindedness and to realize that because the world is becoming more and more global, great and innovative ideas can come from a lot of places and sometimes the most innovative businesses don’t sit in the US.

Considering risks after a great year

[01:06:33] Tilman Versch: That’s interesting. Let me close our conversation with a question for Hayden that came in different forms to me. Considering Hayden’s great performance from the last year, it often happens where great performance in one year is followed by worse performance in following years. What is your opinion on this rotational risk, where the market can rotate away from the sectors you’re mostly investing in? How do you see this risk play a role for you?

I’ve always told all our partners and have talked about this multiple times. Volatility is the price you pay for a strategy like this. If you don’t understand that, you’re probably not right for you a strategy like Hayden’s.

[01:07:21] Fred Liu: I’ve always told all our partners and have talked about this multiple times. Volatility is the price you pay for a strategy like this. If you don’t understand that, you’re probably not right for you a strategy like Hayden’s. Returns are always lumpy. Sometimes you’ll have very large returns in a certain year and sometimes you’ll underperform, but our goal is that over a 10-year period, we will outperform our relevant benchmarks and you know any other potential investment that our partners could have made.

Finding opportunities

[01:08:04] Tilman Versch: Do you have a fear that your strategy makes you look “stupid” with strategy?

[01:08:14] Fred Liu: In our previous interview, I described myself as a pill manufacturer. We do one thing and we do it well, but we’re not right for everyone. If that disease that we’re trying to solve for is no longer in vogue, maybe we won’t have as much of an opportunity set or potential to perform. I would also say that in any macro environment, there are always pockets of opportunity. Maybe it’ll be tougher in the next 10 years than our previous seven, but as a good investor, your job is to really keep as wide of a funnel as possible and go find those pockets. When you’re concentrating like we are, you don’t really need that many pockets to go generate some sort of return for your partner.

Maybe it’ll be tougher in the next 10 years than our previous seven, but as a good investor, your job is to really keep as wide of a funnel as possible and go find those pockets. When you’re concentrating like we are, you don’t really need that many pockets to go generate some sort of return for your partner.

For instance, people call it the mid-2000s as the “Heyday of Value”, like deep value, and you’re what you traditionally think of as a value strategy. Have you seen Tencent’s returns from 2004 until now or even the late 2000s?

[01:09:25] Tilman Versch: No, but they must look very good.

[01:09:30] Fred Liu: Yes, we’re talking like 20x over those few years. You can always find pockets of opportunity and new ideas, especially if you are open-minded and willing to look in other geographies as well. So, Tencent, definitely was not a value stock back in the day, but they still had great performance even though it was the “Heyday” value, and that strategy was most in vogue. You just need to find businesses where the earnings are growing so rapidly that even if the multiple never expands, or you face multiple compression, your net IRR is still extremely attractive. You can find that. The earnings CAGR of a company does not care whether value or growth is in vogue. It doesn’t matter.

You just need to find businesses where the earnings are growing so rapidly that even if the multiple never expands, or you face multiple compression, your net IRR is still extremely attractive. You can find that. The earnings CAGR of a company does not care whether value or growth is in vogue. It doesn’t matter. What these companies’ earnings trajectories are based upon is consumer demand and most consumers don’t even own stocks. They don’t know what’s going on. They just know this is a product that appeals to me. This is what I want. I’m going to spend more of my wallet share on it and the company is going to benefit from that. That’s what you should be looking for.

What these companies’ earnings trajectories are based upon is consumer demand and most consumers don’t even own stocks. They don’t know what’s going on. They just know this is a product that appeals to me. This is what I want. I’m going to spend more of my wallet share on it and the company is going to benefit from that. That’s what you should be looking for. Dig into the actual real economy, not necessarily what other investors are doing, and how multiples are going to fluctuate, especially if you have a longer-term price.

Dig into the actual real economy, not necessarily what other investors are doing, and how multiples are going to fluctuate, especially if you have a longer-term perspective.

Goodbye

[01:10:45] Tilman Versch: Do you have anything to add for the end of our interview?

[01:10:54] Fred Liu: Not that I can think of to be honest. I think you asked pretty good questions.

[01:10:59] Tilman Versch: Thank you very much for your time and for the interview. We still haven’t sent any greetings to Philip for the end of the interview. Hi Philip! Hope you’re good. Thank you very much Fred! Bye bye as in every video.

Also here is the disclaimer you can find the link to the disclaimer below in the show notes. The disclaimer says always do your own work. What we’re doing here is no recommendation and no advice, so please always do your own work. Thank you very much.