South Korea is an interesting country to invest in. With the experts of Petra Capital Management (Website) Chan H. Lee and Albert H. Yong, I had the chance to do a deep dive into this market.

- Introduction

- Habital land of South Korea

- Effects of high density

- Infrastructure in South Korea

- Korea's economic history

- Shift to technology

- Relation between South and North Korea

- Korean stock market before and after COVID

- Korea's stock market culture

- Foreign investments in Korea

- Petra Capital Management's filters for selecting stocks

- Questionable business models

- Samsung as an example of Korean holdings

- Holding discount

- Shareholder culture in Korea

- Activism in Korea

- Good Korean capital allocators

- Cash on the balance sheet

- Buybacks

- Differences to Japan

- Chan H. Lee on playing IPOs

- Petra Capital Management's evolution

- Investing in Tech

- Export driven business models

- Choosing & sizing stocks

- Compounders

- Reopening after COVID

- Chan H. Lee on a compounder example: Kakao

- Understanding Korean culture

- Chan H. Lee on the pace of development in Korea vs. China

- Transformation of Korea's economy

- Government's crisis management

- Thank you, Chan H. Lee

- Disclaimer

Introduction

[00:00:00] Tilman Versch: Good morning, or good day to everyone. It’s great to have you on again for Good Investing Talks. Today I’m talking to two men from Korea. It’s great to have you on Albert and Chan from Petra Capital Management. You’re currently in Seoul, right?

[00:00:17] Chan H. Lee: That’s right. Thanks for having us today. Good morning to you, and good afternoon to us.

[00:00:23] Albert H. Yong: Yeah, thanks for having us.

Habital land of South Korea

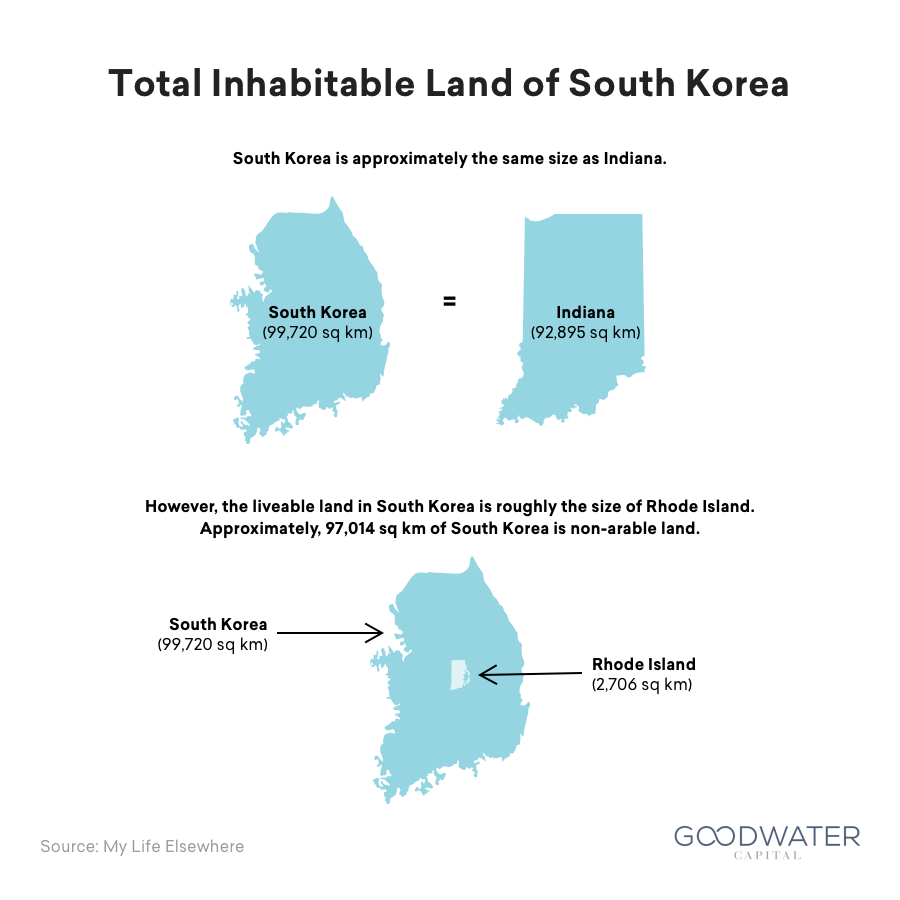

[00:00:24] Tilman Versch: It’s great. You invest for Petra Capital Management. But before we go into the investing stuff, let’s look at some maps I brought for you. Let’s start with this map here. This map is taken from a report by Goodwater Capital. If you want to read the whole report, it is on Coupang, a Korean internet company. You can also find it in the link below.

This map shows the total inhabitable land of South Korea. South Korea is approximately the same size as Ghana to describe it for the people who listen to the podcast only. The livable land in South Korea is roughly the size of Rhode Island, which is only 1/20th of the size of Indiana. So, it’s quite interesting to observe this.

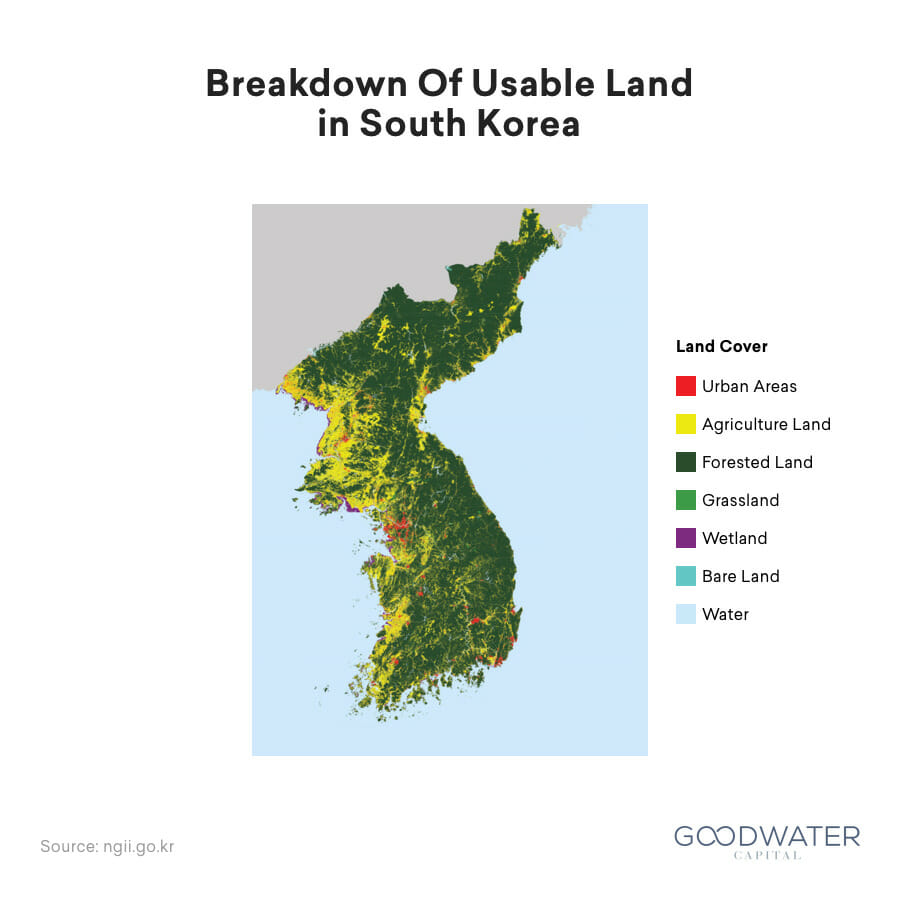

There’s also another version of this map. You can see it here. It’s a breakdown of the usable land in South Korea. It’s quite interesting to see this as well.

So, the first question to begin our conversation is, what is your take on this map?

[00:01:37] Chan H. Lee: Yeah, as you can see, it’s a small piece of land where everybody is living together. Our long history puts a huge emphasis on living together peacefully. Korean people, in general, put a huge focus on civility and trying to live peacefully together. At the same time, because they live in a small space, they have to look at what other people are doing. You have to find an edge in a super competitive environment. In that sense, I think that education was one thing that people found a way to have an advantage.

Our long history puts a huge emphasis on living together peacefully. Korean people, in general, put a huge focus on civility and trying to live peacefully together. At the same time, because they live in a small space, they have to look at what other people are doing. You have to find an edge in a super competitive environment.

Chan H. Lee

Effects of high density

[00:02:27] Albert H. Yong: Actually, about 70% of the land is mountains. Without mountains, if you think about the size of South Korea, the population density is one of the highest in the world. If you look at the inhabitable land, the population density is high. Korean people live in very crowded areas that make us very competitive. We have a very competitive environment.

That kind of environment always has its pros and cons. Somehow, that competitive environment creates a lot of strong and competitive companies. And also, the current phenomenon, Korean pop culture, is from that type of environment. If you look at the area around Seoul, there’s a lot of people. There’s a high population density there.

[00:03:29] Chan H. Lee: Yeah, so South Korea has 50 million people. About 20 million of them actually live around Seoul. Seoul officially has, I think, 11 million, but if you include the satellite cities, it’s nearly 20 million. It’s a very small place with a lot of people, but most people are concentrated around Seoul, which is the capital.

[00:03:53] Albert H. Yong: Think about the land. It’s a very small land. Virtually, South Korea has very few natural resources. If you think about the 1950s, when we had a war, Korea was one of the poorest countries in the world. We had to focus on education. That’s probably one of the reasons why Korea has developed so rapidly over the past several decades.

South Korea has very few natural resources. If you think about the 1950s, when we had a war, Korea was one of the poorest countries in the world. We had to focus on education. That’s probably one of the reasons why Korea has developed so rapidly over the past several decades.

Albert H. Yong

Infrastructure in South Korea

[00:04:18] Tilman Versch: How do you think about infrastructure in Korea? I’ve heard Korea already has 5G rolled out everywhere. Is it easier to roll out something like 5G with this living structure? For instance, if you are somewhere in the East, in the woods, do you also have 5G there? What do you think about this?

[00:04:40] Albert H. Yong: Yeah, of course, it has something to do with the government policy. But again, a lot of people live in very quiet areas, but it is still easy to upgrade when it comes to this kind of infrastructure. That’s part of the reason I always keep it that way.

[00:04:57] Chan H. Lee: Also, Korea has always been known for having a strong manufacturing sector, as well as having high technology. It’s small, and the land itself is small, but they can create these towers that align rather quickly. It’s a combination of land size and the fact that the Korean industry, in general, was already developed so they can quickly build these things.

I don’t know whether this is a good example, but I have a sister in the US, and she’s going through the renovation of her house. She was complaining that it was taking forever. I asked her how long did it take. She said it’s almost six months for a relatively small house. On the contrary, something like that in Korea will take maybe two weeks. So, there’s that sort of tendency for people to work very quickly. And then, there’s that emphasis on getting things done quickly. I guess that means you also have the craftsman’s sheet.

Korea’s economic history

[00:06:03] Tilman Versch: I think you often have visitors from overseas, like Europe or the US, that come for the first time to the country. Did they notice anything special about Korea that foreigners often say to you, like, “I haven’t thought about this.”?

[00:06:22] Chan H. Lee: Obviously, it is like an island. You can’t go to the North. So, shipbuilding, for example, is an industry that was developed early in Korea during the industrial development times, just right after the Korean War, when everything was pretty much reset.

So, shipbuilding was one. And then, based on that technology, we moved on to a lot of construction industry because there was nothing after the Korean War. Transportation, machinery, and things like that are probably one of the earlier industries developed from modern Korean history.

Shift to technology

[00:07:08] Tilman Versch: Is shipping still a topic in Korea? Are there still ships produced?

[00:07:13] Chan H. Lee: Koreans are still considered number one shipbuilders. Of course, there’s Chinese. They’re making strong competition, but Koreans still make all these very highly sophisticated ships. They’re still number one in the world.

Shipbuilding is no longer that profitable. And so, maybe the beginning was more shipbuilding and automobiles and things like that, as well as construction, but now, Korea has developed into other more sophisticated industries like EV batteries, semiconductor chips. You probably heard about Samsung and LG, for example.

It started from maybe shipbuilding and other construction-related industries. I think that perhaps built the base. Now, Koreans are generally pretty competitive in all different types of technology or infrastructure-related sectors, in my opinion.

[00:08:20] Albert H. Yong: Korea is mainly known for high tech, not shipbuilding manufacturing. You mentioned 5G; if you ever visit Korea, you’ll see a lot of technologies already installed in just about everywhere. Even in-house and subway systems. Just everywhere. It’s all high-tech inside the country, basically.

Korea is mainly known for high-tech, not shipbuilding manufacturing. If you ever visit Korea, you’ll see a lot of technologies already installed in just about everywhere. It’s all high-tech inside the country, basically.

Albert H. Yong

Relation between South and North Korea

[00:08:47] Tilman Versch: We will come to stocks and investing soon, but I got so many questions that I still want to talk a bit about the macro perspective. Questions were coming about the relationship with the North. Is there still any economic relationship? Are the two countries separated?

[00:09:10] Albert H. Yong: Basically, the two countries are almost entirely isolated. There was a time when we had a special zone in North Korea where our Korean companies could operate, but it’s closed now. Virtually, it’s a totally separate and isolated economy.

[00:09:30] Chan H. Lee: Because of the North Korean attempt to build nuclear facilities, they are sanctioned by the US and other countries. Therefore, I think it is illegal for any Korean national to do any type of business activity with North Korea at this point. As far as I know, there’s zero activity between South Korea and North Korea.

[00:09:59] Tilman Versch: If the realistic scenario happens and North Korea decides tomorrow to reunite with South Korea, what would that mean? What would be the impact of such a reunification?

[00:10:11] Albert H. Yong: I think, emotionally, most people probably would welcome reunification. But in the end, if you think about the disparity between the North and South, economically and culturally and everything, we might have a problem with merging these two totally different cultures and economies. But initially, people probably will welcome this, I think.

[00:10:39] Chan H. Lee: I mean, it’s a tough question. There’s no doubt that most people in South Korea want this unification to happen eventually. But as Albert mentioned, the difference between South Korea and North Korea is huge now. I guess it’s a much bigger gap than East and West Germany before the reunification.

So, what’s likely to happen is if somehow the leaders in North Korea decide to reunite with the South Koreans, it will be more like a step-by-step approach. Maybe people with certain Visas or business reasons can travel first. They’ll probably take a slow process to be comfortable with reunification.

What’s likely to happen if somehow the leaders in North Korea decide to reunite with the South Koreans? It will be more like a step-by-step approach. They’ll probably take a slow process to be comfortable with reunification.

Chan H. Lee

But in the long run, of course, South Korea is rich, but North Korea is one of the poorest countries in the world. So, this will be a financial burden on South Koreans for a while. But for the long term, I think once the reunification happens, Korea suddenly becomes 75 million instead of 50 million and then is no longer an island.

There will be a straight path to China through North Korea. There will probably be cheaper labour in North Koreans. Plus, South Korea has zero natural resources, but North Korea is known to have some precious metals and resources in their mountains and their land, so this could be a boon for South Korea or Korea in general in the longer term.

Korean stock market before and after COVID

[00:12:29] Tilman Versch: Now, let’s move more into stock market topics. I heard this interesting story about Korea and its relationship with Western investors. There was a phase where many Western investors were coming into Korea because they liked how cheap some stocks and net-net is worth, and they bought them. More came and more bought. And finally, they went back to the value they had before because only Western buyers are buying up these cheap stocks.

How is the stock market culture in South Korea? Is there an independent stock market culture? Do you have new trends like what we have in the west with Robinhood or the Trade Republic that people buy more stocks? Is there domestic interest in stocks? How are things going at the moment for the stock culture in Korea?

[00:13:26] Albert H. Yong: Historically, the Korean market has moved in tandem with other emerging markets. You just mentioned Robinhood, that type of phenomenon in the US. After the pandemic last year, the Korean market has had a similar phenomenon as well. Actually, the Korean market performance was one of the best in the world last year. It’s mostly retail-driven. Foreign investors sold stocks, and Korean institutions also sold stocks. But retail investors, it’s the same until just now. That is a big change. Before, the Korean market was weighed heavily by foreign investors and institutions. But now, we have a large amount of retail-driven trading volume. Maybe it won’t stay as much as now later. It won’t, or at least we think it won’t go back to pre-pandemic days. It’s actually a big change.

[00:14:39] Chan H. Lee: And for the viewers who are not familiar with the Korean market, you saw that the land is small and with a lot of mountains, but we are a very active stock market. Now, the total market for Korean stocks is around 2.1. So, that makes the Korean stock market be 11th largest in the world. It’s actually bigger than Switzerland, and about a similar size to Germany. The last time I checked, Germany was maybe 2.2. So, Germany is a little bit bigger. The German stock market is bigger. But the Korean market is quite large and definitely bigger than Australia, bigger than Brazil and Italy. I mean, Italy is now sort of shrunk a little bit. About 30% of the market participants are international investors. They are meaningful share. You mentioned the American investors, so they come in and go out depending on the global situation and so forth. But now, Korean retail is also a strong player, as Albert mentioned.

Traditionally, I think Korea is influenced by foreign inflow or outflow. But since the pandemic, and maybe going forward, I think there’ll be more, I guess, stability within the Korean market in terms of foreign inflow and outflow. I say that because the Korean people, in general, overall, I mean, they have a lot of wealth, a lot of capital to invest. A few years ago, most Koreans were investing in real estate. I think that’s kind of true for a lot of Asians. But I think there’s definitely a lot of money to be invested in the stock market. As the country develops further, people realize the best way to increase your wealth is by investing in equities rather than real estate or non-growing assets.

A few years ago, most Koreans were investing in real estate. As the country develops further, people realize the best way to increase your wealth is by investing in equities rather than real estate or non-growing assets.

Chan H. Lee

Korea’s stock market culture

[00:16:48] Tilman Versch: Do you have a rough number of how many Koreans hold stocks? Germany, I think, is like 10 to 20%. So, not that many stockholders.

[00:16:57] Chan H. Lee: Technically, the largest investor in Korea is the National Pension Service. That’s the second national pension for everybody. They represent maybe nearly five to six percent. That means basically, everybody’s investing in the stock market because we have a national plan, and everybody’s tied up with that performance of that NPS. I can check the numbers, but I will say the number of people that own stocks could be the big investors versus the young people. They own maybe five, six years of Samsung or something. It’s quite a high number. I think it’s definitely more than the German number. I will say maybe 40% roughly. I don’t have the correct number with me at this point but probably more than 40%, especially after the pandemic.

Foreign investments in Korea

[00:17:55] Tilman Versch: I had some questions coming from private investors on how they can invest in South Korea.

[00:18:02] Albert H. Yong: The best way is probably to invest with us, I think.

[00:18:06] Tilman Versch: I know that answer would come up. Let’s say you want to buy one stock. Do you have an idea how to do this?

[00:18:14] Chan H. Lee: Maybe I can step up a little bit. For foreign investors like yourself who invest as an individual, you’re not allowed to invest in Korea. I mean, that is a big hurdle. To invest in Korea, you have to apply for what’s called a foreign investor ID.

For foreign investors like yourself who invest as an individual, you’re not allowed to invest in Korea. I mean, that is a big hurdle. To invest in Korea, you have to apply for what’s called a foreign investor ID.

Chan H. Lee

So, Tilman, you get up in the morning today, suddenly you want to invest in this Korean K-pop company. Technically, you cannot because you need to be registered with the government. What you could do is you have to go to your broker, maybe Deutsche Bank, and then they’ll make the application process for you. But, typically, with those banks, unless your initial amount is large enough, they won’t go through the process. So, that means it’s not the typical Robinhood type investors even if they know what company to invest in Korea or have some sense of what to invest in Korea. They cannot. So, that is a big hurdle to begin with.

And then, once you go through the process, you typically need to invest X amount of money to help these brokers get this Korean ID. Then, with the click of a button, you can trade in any stock. Actually, if you want to get the ID by yourself, you could do it yourself. You can go to the Korean government site and do that, but it has hassles, so many people end up being discouraged from doing it. But, as I said, the Korean stock market is many companies with over 2000 stocks. There are some big companies like Samsung and LG and Hyundai Motor. There is Apple, but there are many small-cap companies as well. Over 1500 companies are below a billion-market cap range. So, there are a lot of choices. I don’t want to say you go for one stock or better stocks, but it all depends on, I guess, your risk appetite and what kind of investment horizon you have with this opportunity.

Petra Capital Management’s filters for selecting stocks

[00:20:33] Tilman Versch: So, how do you go about selecting the stocks you have in your portfolio? I think you hold 20 to 30 stocks. How do you go about picking them?

[00:20:43] Albert H. Yong: Of course, we cannot just look at every company in alphabetical order. That’s not possible. So, we have more than 2000 stocks listed. And so, we have our screening tool. We narrow down the list. Among those 2000 stocks, about half are probably not investable—basically, our stock is around a thousand. We narrow down that list to more undervalued, more competitive companies. We go through that process, and we always have some companies in the pipeline. From there, we start to research.

[00:21:27] Chan H. Lee: When Albert says ‘not investable’, that means either we’re going to lose money, or they’re too small. So, you have to understand that we in Petra were mostly now managing institutional money, clients’ money. When you manage that kind of money, there are liquidity constraints and things like that that we need to abide by at the same time because we’re a value investor. And then basically, we have a long-term investment horizon.

Every firm has different styles. I’m sure you’re very familiar with the value investing style. It takes a bit of time for us to research and find the company, but once we buy, we tend to be a holder for a long time because by being a value investor, whatever we buy at this point, it’s not probably the market’s favorite stock or favorite positions. So, therefore, given our sort of investment style, given our client base, we have ruled out what’s investable versus not investable.

Given that Petra has been in business now for over 13 years and that we have invested in Korea even before starting Petra, we have a pretty good sense of the good versus the questionable companies. Not only just in terms of profits and loss but the governance and then the management skills and so forth. So, we do have a pretty good shortlist that we review whenever possible. At the same time, we are always looking for new ideas. We look at the new IPO companies and look at the corporate events. We’re very keen on what event could change the valuation of the company.

[00:23:25] Albert H. Yong: So basically, of course, we have a set process, but we are in the business of buying undervalued companies, undervalued stocks, and the value stocks could be just everywhere. It changes from time to time. So, of course, we have our own set of formula-based approaches. But again, we just look everywhere. We look at our existing portfolio companies. We are very curious. We just have to look at all the related companies, their suppliers, their customers. And so, we read a lot. There could be many different ways to find undervalued stocks. So, we just try to do many different things because it could be random sometimes.

We are in the business of buying undervalued companies, undervalued stocks, and the value stocks could be just everywhere. It changes from time to time. There could be many different ways to find undervalued stocks. So, we just try to do many different things because it could be random sometimes.

Albert H. Yong

[00:24:12] Chan H. Lee: Yes. I know that you mentioned the net-nets, but as I said, it’s easy to see, right? Anybody can run the numbers that are trading below cash value. But that means the fact that these companies are staying that cheap for a long time means there’s something wrong with the company. We actually find a lot of net-nets to be, as your American friends have concluded at the end, there tend to be terrible companies or declining businesses. And that’s why they’re trading cheap. Although from time to time, in that net-nets bucket, you can find some misunderstood or mispriced companies that didn’t belong there. With those, we could always invest, but just going into net-nets and looking at the matrix, low PV-low PD, I don’t think that will be the right approach. There’s so much competition going on. There’s a lot of people participating in markets. Yes, the quantitative aspect of the companies and stocks is important, but we think there’s a lot of value in analyzing the quality. That’s where the real intrinsic value comes in.

Questionable business models

[00:25:29] Tilman Versch: You mentioned that there are questionable companies in South Korea. How do you avoid them? What are the practices that you don’t want to see?

[00:25:39] Albert H. Yong: What we mean by questionable is the business itself. Some industries face declining fortune. That’s probably why they trade at a very low multiple—those types of things. Of course, just like in every country, some companies have some problems in accounting and management, but most independent companies have a very difficult situation. That’s probably what we mean.

[00:26:18] Chan H. Lee: I mean, the word questionable may not be the best term to use. But like biotech companies, for example. If the companies continue to lose money, but for some reason, people think that there is a small probability that they could make some new hedge drug that could be distributed to global markets. To us, that is a questionable business model. Of course, those companies could turn out to be homerun. That may work for some people as a potential target company, but given our tendency and disciplined approach, we cannot bet our investor’s money on an unproven future cash flow. That’s what I mean by questionable.

That’s both the companies that are only trading on hopes and the companies that are cheaply valued, but if they’re declining and they’re going to lose out to Chinese, or they only have one customer, you know, maybe like one example. I mean, we mentioned shipbuilding. But perhaps a vendor that works with one large Korean shipbuilder. I mean, the outlook is not that good. So, those companies, we just do not view them to be investable.

Samsung as an example of Korean holdings

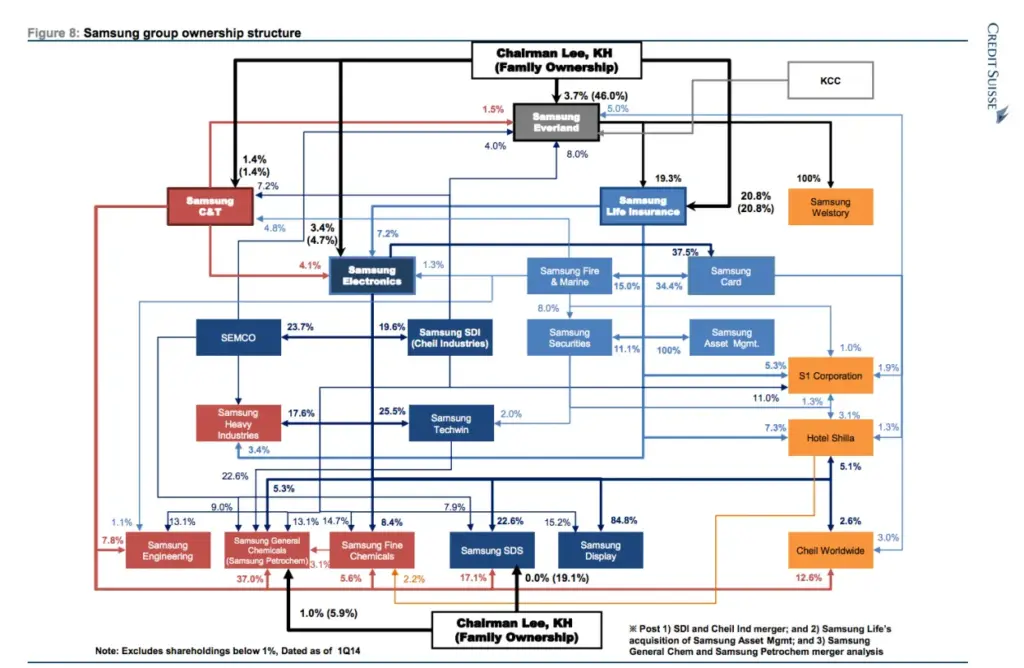

[00:27:40] Tilman Versch: You already mentioned governance. I’ve brought you another chart I want to show you. It’s the ownership structure of Samsung. For those listening to the podcast, it’s a highly complex chart with cross-holdings and cross-holdings and arrows in some directions. It’s hard to understand and grasp. So, let me start with the questions. How do such structures come about? Are they still built today?

[00:28:11] Albert H. Yong: I think it’s the legacy of the old days when Korea first developed the big business in the 1860s or 70s. Back then, the government tried to develop big homegrown companies. Korea didn’t have enough capital, so this kind of very complex structure was probably the only way to extend into different pieces. That’s fine. That’s then. Now we live in a different era, so the problem we have is how to entangle that legacy of the complex structure of big conglomerates in Korea. It started from historical reasons.

[00:29:05] Chan H. Lee: Basically, this is Korean Chaebol. It’s called Chaebol in Korean. This Chaebol Conglomerate model was copied from the Japanese model in Japan. They were more advanced back then. Korea, as you know, was under the influence of Japan for many years. So, when they saw Japan and how Japan developed, the Korean government copied the model. They created a national champion by allowing them to own company A. And then, the money you earned from Company A, you use to then buy Company B and C and D even though they’re not maybe this related type of industries. It’s interesting that you mentioned the Samsung Group. They’re one of the oldest Korean businesses. And so, that’s the legacy. But as you have shown in the diagram, there are many companies owning each other. If you analyze Samsung Group now, there’s only one company worth a lot. That’s Samsung Electronics. That’s over 450 billion. Although they look interesting in the graph, the rest of the other companies are really small dots now relative to Samsung.

The Korean Chaebols or conglomerates have figured out now that the old model of owning many companies or owning bits of these companies and creating many small businesses or small entities is not as good as creating one large one that can be a very global player. So, that’s why many Korean conglomerates are in the process of breaking up e tie. Also, Korean law, by the way, does not allow this type of cross-holding structure anymore. Although some lawmakers wanted to sort of force these companies to break these structures. There will be no more of this in the future. They are just letting the old-style remain. Because of tax and other reasons, it’s becoming more practical for them to unwind these ownership structures. It may take a little bit of time. With Samsung, this ownership of each other will probably remain for a while. But I think if we fast forward 25 years from now, I think this type of structure will be probably a thing of the past.

Discover the Plus Investing community 👋🏻

Hey there!

Discover my Plus community! The community is great for passionate, professional investors.

Here, you can meet investors, share ideas, and join in-person events. We also support you in starting and scaling your fund.

[00:31:39] Albert H. Yong: I think it takes time. Yeah, that’s natural. It takes time unless you have drastic measures. It’s difficult to create extreme measures in a democratic country. Chan mentioned Japan. Japan has the same complex structures dismantled by General MacArthur when the US Army occupied Japan after World War Two. They just dismantled all these kinds of landmarks. And now, it’s impossible to do the same thing. It takes time, but it will be done, I think, in the future in Korea.

[00:32:19] Chan H. Lee: Yeah, but for investors like us, sometimes this type of weird structure or complex structure provides an opportunity. Because the general reaction would be like, you’re a foreign investor who was not familiar with the Korean market, you look at the structure, and how do I invest in any of these companies? You pass on to another target. Yeah. For us, for every company structure, there is maybe an essential company, or there’s a company that looks like it’s intertwined but is actually at the end or is a part of a larger complex structure. It’s straightforward in terms of its ownership. That could be an interesting timing for us.

So, there is an automatic discount when you’re in that kind of complex structure in the middle of these traverse structures. From time to time, some companies, although they’re part of the conglomerates, their ownership structure is toward the end of the web of the organization, or maybe that company used to be a private company but may go public in the future or has gone public. Sometimes this discount is not fair for that particular entity. That also has happened.

Because we’re in Korea, we’re familiar with these types of structures. We’re familiar with accounting treatments and how these structures originated. We’re able to pick the good ones from these bad entities.

[00:33:59] Albert H. Yong: So, it’s an opportunity for us.

Holding discount

[00:34:03] Tilman Versch: How do you profit from such structures? So, one model is that you invest in a company at the end of such a holding structure. And if it gets listed or something, the discount goes away?

[00:34:17] Chan H. Lee: Or it is already listed, but there is a big discount. Because it’s a conglomerate, they have an automatic discount. Later, people will find out that it’s not a discount. Maybe there should be a discount at the holding company level, or if the company owns A and B and B owns C, then there should be a discount.

In the end, one company is part of maybe a hold-co, but is separately managed and independently operating. It’s got good features for the future. Then, that discount should go away, but at the same time, the company itself must be competitive. So for these values to be unlocked or recognized by the market. Not only the discount factor, but if the company itself is growing, the stock price will move up even if there’s a discount.

Meaning we have two ways of making money. One is that we find the right company, they continue to grow or become competitive. So, even with a discount, the value increases. At the same time, there’s a chance that people recognize that this discount is not fair or is too much, then the gap/discount tends to get reduced. That’s how we play with this type of conglomerates or Hoko type of situation.

[00:35:41] Albert H. Yong: I think when there is a discount, some investors are confused because some people might think that the stock can go up, but it’s a different thing actually. Let’s say that the stock’s value is 100 and there is a 20% discount. The value doubles daily. Then, it becomes 160. So, it’s still a 20% discount, but the stock price can go up if the value of the company or the underlying business improves. The existence of a discount, unless it widens, shouldn’t be a reason not to buy a stock.

[00:36:24] Chan H. Lee: And you know Tilman, I mean, the hold-co discount is not just relevant in Korea. Berkshire Hathaway is always discounted. Seoul Bank is also discounted. It just depends. What we like is not the Hoko itself, but sometimes we want to buy the subsidiaries, which are also listed. I think there should be a discount at the whole company level. But at the subsidiary level/operating company level, maybe the discount is sometimes not worth it.

[00:37:02] Albert H. Yong: Yeah, Berkshire Hathaway is a very good example. It’s always traded lower than the sum of the decent businesses. Over a long time, it goes up because of the value of the underlying businesses. They can go up. There’s always a discount. We have a lot of conglomerates in Korea, so we have more discounts. In other countries, the holding companies are always traded at a discount. That’s a fact.

[00:37:36] Chan H. Lee: And then, I know we’re talking about conglomerates and Korean discount, but like I said, there are 2000 stocks. They are conglomerates, but they’re just many independently owned companies that are now part of this old legacy. In fact, nowadays, the more valuable companies are non-related to each other. For example, an internet company, which is not part of the old legacy business of conglomerates. Or pharmaceutical companies or some new technology-related businesses. They’re not part of the conglomerates. And so, there are plenty of opportunities. I mean, we’re choosing 25 to 30 companies in general. We have a rule saying we don’t want to touch any of the conglomerates, but we still have plenty of opportunities, given the fact that we’re able to pick competitive 25-30 companies.

Shareholder culture in Korea

[00:38:36] Tilman Versch: You already mentioned Berkshire Hathaway. This holding has a great shareholder culture and created value for the shareholders over the long term. Do you have such holdings as Berkshire Hathaway in Korea as well?

[00:38:48] Albert H. Yong: I think Berkshire Hathaway is unique in terms of the relationship with the shareholders. Even in other countries, not just Korea, no company is quite the same as Berkshire Hathaway. In Korea, we have many conglomerates, but some companies have some issues regarding governance, but basically, it’s improving. More and more companies are starting to care about minority shareholders. It’s changing, but no company is quite the same as Berkshire.

[00:39:31] Chan H. Lee: Korea for many years had a bad reputation of being not shareholder-friendly. It’s not accounting fraud, cheating, or underhand transactions, but it’s more like treating other shareholders unfairly, which means they never pay dividends that honestly make their best capital allocation decision. You have extra cash. You have the choice of investing in your corvids versus buying a hotel. Sometimes, because of the family’s they decided to go into the hotel business or something that is not as profitable or capital efficient.

So, that’s been the problem. But lately, as I mentioned earlier, there’s NPS, which is the largest shareholder. They’re trying to become more like the Norwegians, the MBM, the CalPERS type, so they become a little bit more vocal. As the Korean stock market gets bigger and bigger, there’s foreign influence. Very sophisticated foreign investors also come in and make their intent to be known. And also, people like us. In Korea, there are now a lot of active managers who are becoming a little more vocal about things. If you think about it, at the end of the day, if the stock price remains low, the biggest loser, in that case, is the largest shareholder, which is the conglomerate owners. Nowadays, there’s more consensus being built around what’s good for the company and good for shareholders having the stock price go up. That means you have to be a little more considerate about treating other minority shareholders that are paying back dividends, buying back shares, and then making the proper capital allocation decision.

[00:41:34] Albert H. Yong: Basically, Korea is very entrepreneurial. We have many new companies developing just every year. If you look at those companies, many of them already have outside shareholders even before going public. They are venture-backed and also have private equity funds. They have better governance. We have more and more research companies. That also did change if you look at large Korean companies.

Korea is very entrepreneurial. We have many new companies developing just every year. If you look at those companies, many of them already have outside shareholders even before going public. They are venture-backed and also have private equity funds.

Albert H. Yong

Activism in Korea

[00:42:05] Tilman Versch: You already mentioned activism. Is activism happening in South Korea? How would you do activism if you want to do it in a good way?

[00:42:16] Chan H. Lee: Right. Activism was not a familiar word five years ago. But now, I think everybody knows what activism is about. Elliott, Management, which is one of the most prominent activist funds, has invested in Korea. It made big news. They invested in Samsung and Hyundai Motor, which are two large companies in Korea. And also, their local activist has started.

And as I mentioned, NPS, for example, has voted against management in the shareholder meetings and so forth. So, this is now becoming more relevant. But still, compared to the US or Europe, the activism type of investment is very small. But I think it’s growing. From our perspective, talking with the management, you’re asking them to do the right thing, I mean, that’s a common-sense approach. It’s not asking them to do anything quite difficult. Look, you have this amount of cash. You haven’t done anything with this cash for the past five years. You’re not growing that much. Then, the best thing for you to do is return cash to shareholders, which is a common-sense thing, right.

So, from our perspective, the best way of approaching this type of activism is common sense with the management and showing them how the math works. And like I said, once again, the biggest beneficiary will be themselves because they own the largest amount of shares. In the Asian culture, people don’t insult you on your face or write nasty letters. Korea is part of Asia. So, I’ll say we have a more shareholder-friendly type of engagement here. I think it’s the right approach. We’ve done some of that. I think it’s the same thing in Japan, but it’s definitely going to be something that would become more and more relevant in the investment space.

From our perspective, the best way of approaching this type of activism is common sense with the management and showing them how the math works.

Chan H. Lee

[00:44:38] Albert H. Yong: Basically, if the environment changes, the companies also change. More and more people become more vocal than I think the companies will respond. One of the difficulties in Korea in terms of activism is that most listed companies have large controlling shareholders. If the shareholders control a large amount of shares, that is inherently difficult. It’s very difficult for them to change. So, we have to persuade and change the environment. Then the company probably will change. Actually, it’s changing. Maybe slower than many people hoped, but it’s changing. That’s a fact.

If the environment changes, the companies also change. One of the difficulties in Korea in terms of activism is that most listed companies have large controlling shareholders. So, we have to persuade and change the environment. Then the company probably will change. Actually, it’s changing. Maybe slower than many people hoped, but it’s changing. That’s a fact.

Albert H. Yong

Good Korean capital allocators

[00:45:28] Tilman Versch: Are there any great Korean capital allocators you could recommend for outsiders to study?

[00:45:34] Chan H. Lee: Yeah. I mean, there’s some. I don’t know how much you’re familiar with Korean businesses or listed companies. But for example, I think H&H is an example. It is a part of LG, the conglomerate, but it’s an LG holding company structure. It belongs as an operating company. It’s a company that is professionally managed. This CEO used to work for Procter & Gamble educating the US. So, he’s been sort of using the capital, acquiring many different related businesses. H&H stands for health and household. So they own like, the cosmetics, the Coca Cola. For example, they own Coca Cola bottling company in Korea. They own this type of consumer-related product. But he’s been able to use that extra cash to acquire other competitors and other businesses and continue to compound the business.

I’ll give you an example. I think there are a few more. Once again, the M&A culture is taking place, but in the US, every day you get up, you see one company merge with another company. The CEO’s job is to be the M&A specialist. You have an incentive to grow your company and whatever compensation is tied to your stock price, and so forth. If you don’t do anything, it’s as if you’re not doing your job.

We don’t have that kind of culture here. But I think it’s gradually and slowly changing. Sometimes I think, for the CEO, the proper job is to say no to certain mergers. I know a lot of mergers end up being capital-destroyed. So, just because you’re acquiring companies, you have to acquire the right companies and then have the post-merger plans.

A good allocator is not doing the deals and just returning cash to shareholders. I mean, that would be another example. We have some companies like that paying out a substantial amount of their extra cash to shareholders.

Sometimes the CEO’s proper job is to say no to certain mergers. I know a lot of mergers end up being capital-destroyed. You have to acquire the right companies and then have the post-merger plans. A good allocator is not doing the deals and just returning cash to shareholders.

Chan H. Lee

Cash on the balance sheet

[00:48:22] Tilman Versch: Is it common in South Korea that companies hold a lot of cash on their balance sheet like Japan? What is the reason for this? I’ve heard that Japanese companies needed this cash because banks are bad with financing in Japan.

[00:48:43] Albert H. Yong: In Korea, it’s in a way similar the lending is not favorable. That’s one of the reasons. Another reason is in Korea, we had a very severe financial crisis, like in 1987. Before that, most companies in Korea were leveraged. After going through that crisis, that changed everything. Most companies thought that for the next crisis, they thought that they needed to accumulate enough capital, but things changed. Now, more than 20 years have passed, but still, a lot of companies’ sentiments is tied to that. So, there’s a crisis. That’s probably one of the biggest reasons some Korean companies sit on top of large amounts of cash.

[00:49:41] Chan H. Lee: During the Asian financial crisis in 1997-1998, many large companies went under because they were very clever. So, when they survived, they have that sort of the still bad memory of the company being too much lever, so they end up being under levered or over cash.

And then, after the Asian crisis, Korean companies start to recover. And then, they went through the global financial crisis, which was more US-driven. But still, they kind of saw the same thing, although data cleaning companies are not that effective because they’re already we’re holding a lot of cash. And so, basically, they kind of reinforce the idea that holding cash is good. And then, even during the pandemic. Although in 2020, the US government quickly printed out money, everything was back to normal quickly. But initially, some foreign investors have started to call us saying, “Oh, now it’s time to invest in Korea because Korean companies are cashing. They’re not going to go bankrupt.”

So, depending on the market situation, how things are happening/taking place globally, sometimes having some cash balance, I think, is good for the shareholders. However, in Japan, they went too extreme and Korea to a certain extent, but it’s also a function of these Korean companies becoming very profitable. So, it’s not their intent to just sit on cash, but there’s a key to making money.

Depending on the market situation, how things are happening/taking place globally, sometimes having some cash balance is good for the shareholders.

Chan H. Lee

Buybacks

[00:51:17] Tilman Versch: Do you see sophisticated buybacks happening in South Korea like the people repurchase stocks when there’s a discount to intrinsic value? Or are there any buybacks at all in South Korea?

[00:51:30] Albert H. Yong: The buyback in terms of the number of buybacks is relatively small compared to the US. But on the other hand, when you look at the US situation, and most companies buy back their shares at an elevated price, so that’s not the sensible way of privately owned shares. It’s the opposite. But Korea, I think, traditionally buys back shares to increase the shareholder value. Has been somewhat aware, but it’s increasing. That’s a new trend.

[00:52:07] Chan H. Lee: Larger companies like Samsung, Hyundai have started doing it. And then, a lot of mid-sized companies start to follow. And also, like I said, they are seeing cash. And then, if they don’t have any plan to use cash, the best way to use cash is by buying back shares. Buying back shares is more favorable in terms of tax treatment for business owners. So, when a stock price is down, they tend to buy back shares and keep the stock price competitive. I think some sophisticated CEOs have started to buy back shares. It’s not as active as the US in any way, but it has started. The movement has started.

If they don’t have any plan to use cash, the best way to use cash is by buying back shares. Buying back shares is more favourable in terms of tax treatment for business owners. So, when a stock price is down, they tend to buy back shares and keep the stock price competitive.

Chan H. Lee

Differences to Japan

[00:53:00] Tilman Versch: Is there a dividend gift culture in South Korea like in Japan? People get food or whatever as a dividend gift. This is popular for stock owners to wait for such presents as a dividend.

[00:53:19] Albert H. Yong: No. No.

[00:53:21] Chan H. Lee: I mean, it’s not a dividend, but when you go to shareholder meetings, they’ll give you a present. For example, when people come to a shareholder meeting, they’ll receive a pan or something as a sort of a gift, but it’s not part of the dividend.

[00:53:37] Tilman Versch: Okay. Then it’s just a Japanese thing. There’s one guy who made this gifting culture very popular. He also made stocks famous. Let’s talk a bit about the IPO market in South Korea. Is it a bit like Germany, like we have many interesting companies that aren’t public, held private, and don’t need to go to the stock market? Or how is it in South Korea a company is easily gravitating to the stock market, and they’re doing an IPO?

[00:54:09] Albert H. Yong: I think most private companies in Korea who want to go public are mostly in the technology industry. Venture capital funds usually finance them. So, usually, those outside investors have to exit, so they always think about going public. It’s quite vibrant in Korea. Most companies, those types of companies are not family-owned traditional businesses. They’re primarily venture-backed technology companies. So, basic. The path for them is to go public. It’s pretty natural, and that’s very vibrant creative.

I think most private companies in Korea who want to go public are mostly in the technology industry. Venture capital funds usually finance them. So, usually, those outside investors have to exit, so they always think about going public.

Albert H. Yong

Actually, if you look at the Korean venture capital industry, it’s quite sizable now. The venture capital funding, the investment size investment compared to the GDP in Korea is only behind US and China as third in the world. It’s quite vibrant. So, as many companies go public and a lot more these days than before. So, it’s different because mostly they want to go public.

[00:55:17] Chan H. Lee: I guess unicorns are the ones that could go public anytime. Surprisingly, of course, the US, China, and there’s India. After that, maybe, UK and Germany. I think Korea has the most number of unicorns. I think, maybe 12 or 13 at this point. There are smaller ones that are going to be unicorns.

I understand in Germany all the good companies never go public. They stay within the family. But here, we don’t have that kind of mentality. So most people want to go public. And also, it’s usually a sign of success here when you operate a public company versus a private company. Even though a private company may be more profitable, people tend to recognize public companies more. So here, all the good companies. I mean, there are, of course, there are some exceptions here and there. But generally speaking, they end up going public. So if you’re investing in Korea, there’s an opportunity also to get access to these great companies. They’re coming in from New IPOs.

[00:56:33] Albert H. Yong: It’s like a disease in Korea. It’s quite rare for large sizable private businesses to stay private. It’s pretty rare these days in Korea.

Chan H. Lee on playing IPOs

[00:56:46] Tilman Versch: How are you profiting from IPOs? And how are you playing IPOs as an investment case?

[00:56:52] Chan H. Lee: When we analyse companies, as you know, generally we look at public companies, but as a part of our analysis, we have to look at their competitors, new players, and so forth. And then often, they are non-public companies. So, we do have the chronology of the size of all non-public companies.

As Albert mentioned, they could go public anytime because of the trend. And then, these companies are typically backed by private equities or venture capitalists. We do pay close attention to them. When they go IPO, we look for the right opportunity to buy into these companies. Sometimes, given the market sentiment, we can participate in IPO, or often, we wait until the company goes to IPO, and then usually there is a pop. Then there’s a decline. It then allows us to buy in these companies at a discount price.

Petra Capital Management’s evolution

[00:57:58] Tilman Versch: You’ve been investing since 13 years ago in South Korea as Petra Capital. If you have a time machine and can go back to 2009, what will you do differently? What kind of stocks would I find in your portfolio that I won’t find there today?

[00:58:20] Albert H. Yong: Basically, we buy undervalued companies. Undervalued companies are always present at different times and in various industries. So, if you go back to 15 years ago, we probably would have bought undervalued companies in that time. Basically, we are actually agnostic to industries, so presumably, we would have bought undervalued companies in different sectors than now. That’s how I think about it.

[00:58:56] Chan H. Lee: I think the market changes so fast that you must adjust. I mean, we are value investors in our hearts, but value could mean different things for different people. I don’t know. Fifteen years ago, maybe, you know, you mentioned net-nets, but net-nets were more attractive back then than now, for example. Fifteen years ago, we would have bought companies that are more cash flow-focused. Coca-Cola type of companies will be a good example. We would have bought that because it has a stable cash flow. But for example, you fast forward now, whatever has stable cash flow for the past five years, sometimes it’s not as meaningful because things are changing so fast and there are newcomers with different models. To be a successful value investor, I think you have to find, of course, undervalued opportunities or discount opportunities. But discount or undervaluedness could come from different factors.

I think the market changes so fast that you must adjust. I mean, we are value investors in our hearts, but value could mean different things for different people.

Chan H. Lee

Follow us

Investing in Tech

[1:00:04] Tilman Versch: Is the change in the Korean stock market to a more tech-oriented stock market also affecting you, your models, and your thinking?

[1:00:14] Albert H. Yong: So, we now own more tech companies. That’s true. But that’s not because we just bought for the sake of buying technological companies because it’s hot. We just found that more competitive companies are now in the technology sector. As I mentioned before, many Korean companies in the technology sector are growing very fast and are very competitive. So, that’s probably why we own more techs.

We now own more tech companies. That’s true. But that’s not because we just bought for the sake of buying technological companies because it’s hot. We just found that more competitive companies are now in the technology sector.

Albert H. Yong

[1:00:43] Chan H. Lee: It’s tech, but you have to think about it. I mean, is Amazon a tech company? I mean, it’s a tech company, but it’s also a retail company. People used to go to physical places to buy things, but now people buy online. There’s a change in how people behave or buy things and sell things. I think Korea is definitely going through the same process or changes.

We find opportunities in these types of tech companies. I guess some tech companies are more tech-driven, like semiconductor companies. We don’t eat some internet businesses as tech companies, but we view them as either consumer brands or retail. So, I guess the notion that we could categorize these companies by different sectors is not an exact science.

We go wherever the opportunity is. As mentioned, nowadays, especially in the past few years, there’s a transformation of everything going digital. And so, a lot of companies that we own in the tech sector are the companies that are going through that change and are also the beneficiary of this digitalization of content and products.

We go wherever the opportunity is. There’s a transformation of everything going digital. And so, a lot of companies that we own in the tech sector are the companies that are going through that change and are also the beneficiary of this digitalization of content and products.

Chan H. Lee

[1:02:19] Albert H. Yong: If you look at the US stock market, many dominant companies are dominant in most countries in the world. Korea is one of the exceptions. In Korea, we have our homegrown domestic companies that are dominant in many areas. That’s why we have many opportunities in that sector in Korea.

[1:02:43] Chan H. Lee: I think Tilman, I had mentioned this to you before. Everybody in the world, when they listen to music, they use Spotify. That’s sort of the global brand, or that’s what everybody seems to use. But in Korea, a company called Melon is now part of Kakao Entertainment, which was already making music streaming almost ten years before Spotify. It only happens that they were only operating in Korea. Nobody else was streaming music because they didn’t have enough and proper infrastructure. You need to have appropriate streaming. You need to have fast internet, fast devices. So, Korea was the first one to do it.

And so, when you come to Korea, Melon is still number one. Spotify has a very small market share. However, I guess that’s not a problem, but the limit of that company is they are only growing within Korea. Their upside is pretty much limited. So since then, a lot of companies that have become successful in this type of innovative product or content realize that the opportunity is bigger outside of Korea. So, you see a lot of Korean tech companies or content providers that have gone to Japan, have gone to China, and then they move their business model outside of Korea, and they become a much bigger company. I see that as a very positive change.

Export driven business models

[1:04:19] Tilman Versch: Korea seems to be very export-oriented. Do you have a rough idea about the revenue share that goes to export and that is Korean in your companies?

[1:04:32] Chan H. Lee: Okay. Maybe I’ll talk about general markets. General market because Korea is this sort of island, so they had to earn money outside. At the company level in general, 70% is probably export-oriented or maybe even more. They are 30% domestic Yeah.

However, the companies that we own are probably 50/50 at this point. It’s not just our choice. We go whatever is an excellent opportunity, and we see some domestic companies are still growing within Korea, more like domestic internet businesses and so forth. Right now, it’s probably 50/50. Do you want to add anything, Albert?

[1:05:25] Albert H. Yong: One of the companies we own, more than 95% of the revenues actually come from outside of Korea. That’s one extreme example.

[1:05:36] Chan H. Lee: What’s interesting is that it’s not the traditional company you’re thinking about. The Korean shipbuilders or Korean Samsung selling cell phones. I think the 95% revenue that Albert is talking about is a renewable energy company. It’s a wind power company that probably nobody outside the investment world, and also the wind power sector has ever heard of. Somehow this company figured out their business model, and they just went global from the beginning. And also, the fact that the wind does not blow strongly in Korea. That’s another reason why they were not able to make it big out here. But with their technology, they went global. They went to Europe, the US, and 95% of their revenue is from overseas in the renewable sector, not the traditional sector you’re thinking about, which may be the machinery and the manufacturer.

[1:06:35] Tilman Versch: How many stocks do you hold? What kind of stocks are these?

[1:06:40] Albert H. Yong: We typically own around 20. But at the moment, we own fewer than 20 stocks.

Choosing & sizing stocks

[1:06:45] Tilman Versch: How do you decide to invest in new stock? How do you choose certain positions?

[1:06:54] Albert H. Yong: We own probably as low as 3% to 10% in terms of sizing. That’s our way of sizing. It depends on the competitiveness of the underlying business. Also, how much is it undervalued? There are many factors. That’s how we size our portfolio.

[1:07:19] Chan H. Lee: Yes. As we mentioned earlier, we are sector agnostic, so we go wherever the opportunity is. It’s often undervalued investments. At any given moment, there’s a certain sector that will be heavily undervalued or discounted for the right reasons. Before, it used to be oil and gas. Sometimes it would be a bank. If you ended up by a whole bunch of banks, that’s not good for you. So, part of our portfolio construction is risk management. So yes, we go for whatever the highest discount is; undervalue is great. But we do look at risk factors. We don’t want to put all of our companies in one industry or several industries. We do think about those things when we pick companies. If you look at our portfolio, it’s a pretty well-diverse five-sector allocation at this point.

Part of our portfolio construction is risk management. We don’t want to put all of our companies in one industry or several industries. We do think about those things when we pick companies. If you look at our portfolio, it’s a pretty well-diverse five-sector allocation at this point.

Chan H. Lee

Compounders

[1:08:25] Tilman Versch: So, what is the size of specific sectors if I look at your portfolio? How many components do you have? How many special situations are you invested in?

[1:08:39] Albert H. Yong: It also depends on the environment. But at the moment, we own, I’d say, more compounders than commoditized. It depends on the opportunity set at the time.

[1:08:50] Chan H. Lee: Because, as you know, Korea is still one of the cheapest markets in the world. The year 2020 was unusual. The Korean market performed very well after the pandemic. Before that, it was always underperforming. We still think that some of the companies that remained despite the stock price going up last year were still undervalued. They could compound or grow even further, especially when things reopen. I know there’s a Delta variant, and there are all kinds of uncertain factors, but at the end of the day, I mean, we expect the economy will go back to normal. And then Korea being a net exporter, they’re likely to benefit from the reopening of the global economy.

Reopening after COVID

[1:09:45] Tilman Versch: How will the companies you own profit from the reopening?

[1:09:49] Chan H. Lee: Because they are exporters. As Albert mentioned, some of the companies get more revenue from overseas. As their brand gets stronger, they make more money. Maybe initially there 50% of revenue comes from overseas. Now, that becomes 70% to 80%. What’s popular in Korea is now popular in Singapore, Japan, China, and maybe even Germany. For more business activities, I think these Korean companies are likely to benefit from the increased business activities, more global buyers.

[1:10:34] Albert H. Yong: But then again, rebound and reopening are related recoveries. Sometimes for medical decisions one time, we look at many companies, they strongly rebounded recently, but the performance before the pandemic was not good. In that case, the fortune won’t change after a one-time recovery. We focus more on long-term outlook instead of one-time recovery.

Rebound and reopening are related recoveries. We focus more on long-term outlook instead of one-time recovery.

Albert H. Yong

Chan H. Lee on a compounder example: Kakao

[1:11:03] Tilman Versch: Maybe you want to share one or two examples of compounders you invested in. And maybe also tell us why you like them and why you invested in them.

[1:11:13] Albert H. Yong: One company I will talk about is this company called Kakao. It started as a messaging app, similar to WhatsApp. Kakao started before WhatsApp and other messaging apps in other countries. When it first came out, we just didn’t use the chat function using that messaging app. We looked at how other similar companies are doing in other countries and how they could profit in the future. We look at many related industries where this company could morph into whether there’s already a dominant player in related sectors and so many things.

Some companies in other countries, for example, let’s say, China have WeChat. They probably went ahead and started to make profits. We looked at Kakao and whether they can do similar things in Korea. We just realized that Kakao could go into other related businesses and leverage the massive dominance of messaging apps in Korea. That’s why we get this Kakao. But when we first bought Kakao, many investors in Korea didn’t realize the potential value was trading at a very cheap price. Suddenly, going through the pandemic, people realized the potential value of this company. We realized and knew that the company’s interest value is growing and still growing. So, that’s one of the compounders we own at the moment. It’s one of our successful investment opportunities.

[1:13:12] Chan H. Lee: Ninety percent of the Korean population uses Kakao. I know in Europe, they use WhatsApp. In China, they use WeChat. It’s kind of regionalized, but in Korea, it’s still 90%. And so, with that type of customer base, they developed into an Uber type of tech-hailing app, which is their number one. I mentioned streaming music. Kakao acquired this company, Melan, to service streaming music. And then, they also went into other contents businesses like webtoons. I don’t know if you’re familiar with that concept, but it’s comics people read online. Also, they went into FinTech. Because of their dominance in the chatting or the messenger app with the right CEO, they’re able to grow their business into related businesses.

For example, in the US, you have Facebook. You have Uber. Paypal is a different company also. On the other hand, you have every function of those various apps in one Kakao app. There’s a messenger app, FinTech, taxi-hailing app, and even now games added as well. Lately, they are getting into regulatory issues of antitrust law and things like that because they’re becoming bigger and bigger. But overall, I think they have reached a certain point where they’re going to be dominant for many years, and they’re going to be more profitable.

[1:15:06] Albert H. Yong: It just started as a messaging app. Now it has morphed into a big business, which is dominant in many different areas. As Chan expounded, this is a combination of Facebook, PayPal, Uber, the large internet bank, and mobile game. Just many different fields that are dominant in Korea.

It just started as a messaging app. Now, Kakao has morphed into a big business, which is dominant in many different areas.

Albert H. Yong

[1:15:30] Chan H. Lee: And then, how they structure is also interesting. Instead of doing it in one corporation, they have created each operating company separately with different CEOs. Although it is part of Kakao, they work independently, and they compete against each other. And then, each time, they win a special part of the business. They have received investment from global private equity firms or other players like Tencent to keep their evaluation going. And some of these were IPOs, which definitely had a positive impact on the Kakao stock price. We think that there are going to be a few more entities that will go IPO. So, this is one of those compounders with a catalyst that would add value to the total valuation. Kakao, I think, is now among the top five companies in Korea with over a 70 billion market cap. It was a very quick rise, but a lot of work was done that made them ready to be this big empire.

Understanding Korean culture

[1:17:34] Tilman Versch: So, maybe let’s go back to the beginning and link our conversation with it. We talked a lot about the culture and the uniqueness of South Korea. So, if you think of an outside investor coming to Korea, what would he miss if he wouldn’t invest with locals and doesn’t have the local knowledge?

[1:17:58] Albert H. Yong: I think people outside of Korea, unless it’s a very sizable company like Samsung Electronics, would find it difficult to understand the business. I mean, not just the business but the culture. When you make an investment decision, one of the most important factors is management. It’s very difficult to understand the capabilities of Korean management because of the language barrier, cultural differences, and sometimes you have to be on the ground. So, those factors, I think, are the difficulties that most foreign investors face when they invest in Korea.

When you make an investment decision, one of the most important factors is management. It’s very difficult to understand the capabilities of Korean management because of the language barrier, cultural differences, and sometimes you have to be on the ground.

Albert H. Yong

[1:18:49] Chan H. Lee: It’s kind of similar things that you face when you invest in Japan. If I had to pick two countries that speak the worst English, it’s probably Japan and Korea.

[1:19:02] Albert H. Yong: Yeah.

[1:19:03] Chan H. Lee: I mean, the younger generation is different, but I’m just saying in terms of language, and this is another interesting point, but the Korean language is very, very different. If you had to pick one language that is very different from English, Korean would probably rank in the top three. Germans have the same alphabet, so I know you speak very fluent English. And of course, you’re probably a student. For Germans, it is more natural to learn English, whereas, for Koreans, it’s completely different with the word order and even the sound.

Especially the older generation. People will have difficulty learning English. While they may be smart in their own way, they’re not good at expressing what they want to do in English. Also, we see that in disclosure statements. For example, in Korea, disclosure rules are pretty good, but they’re not required to produce them in English. So, if you look at the Korean version, it will be maybe a hundred pages. It will be very detailed. Then, they will produce an English version with a 10-page summary. So, for a non-Korean-speaking person investing in Korea, you have this disadvantage even though the larger companies produce everything in English just for the sake of their IR with foreign investors.

And then, also another thing is the diagram that you showed us earlier, the Cheobol structure. Whatever bias, if they see anything complex, they will say, “Oh, there must be doing something questionable. This is not analyzable.” So, they have a good excuse saying, “I don’t want to do work.” As I said, it is not always the case, but sometimes we find opportunities in cases like that. And so, that’s another big disadvantage when you’re not familiar with the market.

And also, Korean history, as I mentioned, is long. It’s 5000 years. But if you look at Korean capitalism history, it’s relatively short. It only started in the 1970s. So, for people who have been in Korea for many years studying Korean markets, Korean history, Korean financial markets, we know our knowledge about the Korean market is much more profound. I don’t want to sound pretentious, but if you’re investing in New York or you are investing globally, yes, maybe your knowledge level may be higher in terms of investment in certain sectors, but when it comes to investing in Korea, we do have a competitive edge because we know the history inside out. What are the dynamics? Why did this company go bankrupt? Which family has a bad reputation, good reputation? I think this will be inherently difficult for outsiders. It’s kind of similar problem that a lot of international investors have in Japan. But maybe to more extent.

[1:22:32] Albert H. Yong: We found out quite instantly to many US or European investors that they understand Southeast Asian companies better than Korean companies. As Chan mentioned, Korea and Japan are probably the hardest to understand. Sometimes foreign investors come to Korea to meet some companies. I’m not talking about the really large companies but small companies. They bring an interpreter/translator, but still, they misunderstand. It’s very difficult actually.

[1:23:09] Chan H. Lee: Yeah. And also, the fact that sort of the global banks like Goldman Sachs or JP Morgan only cover larger companies. And so, a company like CS Winn, I mean, they’d certainly cover LG Chem very deeply, but a company like CS Winn would never come to their radar. In fact, even within among the Korean brokerage firms, there was not much coverage when they were small. But now, there’s a lot of coverage. And now there’s also English coverage. But, you know, there’s definitely an opportunity for us to get in there before the company becomes large.

Chan H. Lee on the pace of development in Korea vs. China

[1:23:45] Tilman Versch: How fast is Korea changing? I had some discussions with Chinese investors, and they say you have to have people on the ground to understand the change. And even after two or three years, it can be different. Is Korea changing that fast as well?

[1:24:00] Albert H. Yong: They are still changing very fast. At the development stage of China, of course, at that stage, it’s changing very fast in Korea back in the 80s. I think that China, the current development stage China is more similar to the 80s or early 90s Korea. Korea changed faster than now. But still, we think Korea is changing very fast. It’s quite different from five years ago, even more so compared to 10 years ago. Very fast, actually.

[1:24:35] Chan H. Lee: Yeah, probably a lesser pace than China for sure because Korea is growing at 2% – 2.5%. But certainly, I talked to friends that visit from Europe or US. They are regular visitors. Every time they come here, they are like, “What happened to this tower?” Or, now we have all new devices. It’s more changing. Especially the younger generation.

I mentioned the lack of language skills. I don’t know. Maybe that’s the problem a lot of parents had, so I think the new thing for Korean parents to do is send their kids overseas to learn English and other languages. You see cranes all over the US, all over Europe. I’m sure you see a lot of Koreans in Germany as well. So, when they come back, they bring in different views, different perspectives. So, that’s making changes.

Some traditional people don’t like it. Why are Korean people dyeing their hair in this color or that color? Why are they dressing this way? So, there is that sort of conflict between the generations, which is another topic to discuss. So, we see a lot of that taking place.

I have three sons in high school. One in high school, junior high, and in elementary school. Their mentality, even amongst the elementary school student to high school, is quite different. One kid may be used to using a cell phone only. He kind of skipped the computer and went to his cell phone. Whereas the older one, he used cell phone too, but he started his internet with a computer. That’s how they behaved, how they enjoy their products and content. It’s already different. It’s probably the product of both worlds changing and Korean people adapting fast to this type of environment.

Transformation of Korea’s economy

[1:26:55] Tilman Versch: For the end of the interview, I want to give you the option to add something we haven’t discussed. Is there anything you want to add?

[1:27:01] Albert H. Yong: I want to add that many foreign investors believe Korea is dominant by the cyclical industries when they think about Korea. That’s right, if you look back at five, maybe ten years ago. But now, if you look at the largest companies in the Korean stock market by market cap, it’s an all-new economy that we have. Semiconductors to buyers, to a mobile platform, to EV batteries. It’s all changed. If you look at worldwide, only probably the US stock market is comprised of new economy companies. Of course, I’m not talking about their valuation. But that tells you about that transformation of the Korean economy. So basically, Korea used to be the cyclical interest dominant. Now, it’s secularly growing new economies. I think that in that sense, Korea has an excellent outlook.

Korea used to be the cyclical interest dominant. Now, it’s secularly growing new economies. I think that in that sense, Korea has an excellent outlook.

Albert H. Yong

Government’s crisis management

[1:28:13] Chan H. Lee: Yeah. I want to add about maybe a different topic. It’s related to Coronavirus and how the government dealt with it. It kind of shows how the Korean people are very efficient or how they operate things. For example, I know Europe, most of you in Germany and other countries are probably 70% – 80% fully vaccinated. But Korea, they were late on getting the vaccine, so it’s still less than 60%, although we’re going to get to 70% within a couple of months. Just give you a sense of the number of cases.

There are 50 million people in Korea, right. Cumulative cases are 300,000. I know it’s 83 million in Germany, but four million in the number of deaths. Korea has less than 2500. Germany is at 90,000. The UK is a slightly bigger country than Korea. The number of deaths in Korea is once again 2500, UK 130,000. The number of total cases, 300,000 versus seven million or almost eight million now.

Think about it. Coronavirus started in China and came to Korea very fast. At the time, nobody had vaccines. Right? It shows how Korea is very efficient at managing this type of crisis. You saw the map earlier. Korea is a very dense country. They all live in Seoul. But the subway, bus, public transportation is still operating.

[1:29:53] Albert H. Yong: Yeah, public transportation.

[1:29:57] Chan H. Lee: I talked to colleagues in Europe and US. Everybody’s working from home. But for us, we didn’t have to work from home. I mean, we only recommend to those people that want to stay home for whatever reason. But right now, Korea, it’s almost back, even when the vaccination rate is less than 60%. That’s kind of showing you something. Of course, there’s a reason why they were able to handle this situation well, but it’s the contact tracing through the app. They have an efficient hospital system. Everybody’s online.

I don’t know how you are doing it in Germany, but everything is through an online app in Korea. I can see which hospitals are giving the shots at exactly what time, where, and things like that. There could be a little bit of infringement on the privacy issue for people infected with the virus. They quickly found out, and then they were sent to this facility. Then, they had to disclose who they were with for lunch and dinner. Sometimes a hidden girlfriend got discovered in the process like that, which was an issue initially. But in the end, it shows that Korea is very good at managing this type of process and crisis management.

What I noticed about Korea’s upgrade is that whenever there’s a crisis, Korea tends to do a little bit better. As Albert mentioned, in 1997, Asian financial crisis, a lot of jobs were lost, many companies went under, but after that, Korea became a different nation. And then, during the global financial crisis, when things were bad, Korea was able to upgrade itself and go more global. I think this pandemic is another example of how positive things will happen for Korea. This is when people start playing Korean games, online games. They begin to stream Korean music. You have probably heard about BTS and others. They’re not popular amongst men, but certainly amongst teenage girls all over the world. I don’t know if you watch Netflix. A new drama called Squid Game became number one everywhere, I guess in the world, but it’s a Korean-speaking drama. So, either you can dub it or read the subtitle, but it became number one. I think that the CEO of Netflix recently said that this program might become the largest.

[1:32:47] Albert H. Yong: All-time best in Netflix history.