I had the pleasure to welcome Per Brilioth of VNV Global back. Here we focussed on the impact of Russia’s war and VNV’s investment in Babylon Health stock and VOI.

We have discussed the following topics:

- Introducing Per Brilioth

- VNV's involvement in Russian & Ukrainian companies

- Areas of investments affected by the conflict

- Per’s communication with companies

- A change of strategy for the emerging markets?

- Consequences for other investments

- Who is selling?

- Impact on NAV

- Valuations in the private vs the public world

- Investment breakdown

- Are you turning into an “asset manager”?

- Managing the portfolio

- Outlook on different portfolio companies

- Thoughts on SPAC listings

- Babylon Health stock

- How can Babylon win in healthcare?

- AI's challenges

- Babylon's acquisition strategy

- Winning the US market

- Measuring Babylon's success

- The future?

- Community Exclusive: Surprises in VNVs journey: VOI

- VOI's innovations

- VOI's strategy to become market leaders

- New team members

- Growth and the corporate culture

- New horizons

- Closing thoughts by Per

- Staying optimistic during change

- Thank you & goodbye

- Disclaimer

Introducing Per Brilioth

[00:00:38] Tilman Versch: Hello, everyone! It’s great to have you back on Good Investing Talks. And after one year, I re-invited Per Brilioth of VNV Global. It was quite a moving time, and it still is today, especially if you look at the markets and the current turmoil in Russia. And that’s also the bridge to our first topic.

We don’t want to go into being war analysts at this point, some people have way more expertise than us, but we have Russian history. Let us talk about Russia a bit.

VNV’s involvement in Russian & Ukrainian companies

[00:01:24] Tilman Versch: When was the last time you had significant exposure to Russia?

[00:01:28] Per Brilioth: Well, define significant? At the end of last year, we had like 3.8% in Russia and Ukraine in companies based there. So in absolute numbers, that’s a lot of money. In relative numbers, is a much smaller percentage of the portfolio. If we had talked at the end of 2018, we had like 60% in a veto, which is Russia’s classified player, but that’s no longer here. So in economic terms, that’s a much better situation because visibility into assets over there is very low right now.

Areas of investments affected by the conflict

[00:02:16] Tilman Versch: What kind of visibility do you have? With the current conflict, what foreign investments are affected in your portfolio?

[00:02:26] Per Brilioth: Well, one of our investments, there is one to trip. That’s like the russianbooking.com. And there’s quite a bit of travel going on over there now, even today. So they’re doing okay, but if circumstances continue, it’s hard to see if there will be any travel, right? And there’s certainly no foreign travel or very little foreign travel. And so that’s one. We have another company, which is like a marketplace for long-distance freight. That kind of situation, of course, still goes on. In Russia, there’s no war, so life goes on. But there’s very high inflation, and unemployment is coming up and all of that. Still, the economic environment is not good.

So I guess both of those will be affected by that. We also own a digital insurer for health, like an “Oscar Health of Russia.” And that product, I guess, over time, will still be needed, but it’s also very uncertain. So visibility overall is very low for those kinds of companies.

In Russia, there’s no war, so life goes on. But there’s very high inflation, and unemployment is coming up and all of that. Still, the economic environment is not good. So I guess both of those will be affected by that.

Per’s communication with companies

[00:03:52] Tilman Versch: How have you gone about as the crisis started with the communication with the companies? What have you done at this point, and how has it evolved over the last weeks?

[00:04:05] Per Brilioth: Yeah, so we talked to all of them. And we’ve talked about all sorts of things with them. But all of those companies have people in them, some who have relatives in Ukraine, and some have offices in Ukraine. So Ukraine is a big tech market, and from a tech perspective, many people have sort of staffing across both countries. So that’s very problematic now. Of course, beyond having people in Ukraine get to someplace where it’s safe. That’s the current priority number one.

We talked about those things because it’s impossible to fund those companies just to ensure they are in good shape. After all, we don’t know when there’ll be any circumstances for those companies to get funding. So they need to stay alive or go out of business. So from a valuation perspective, I think it’s almost a complete lack of visibility.

Of course, one way to go about them in terms of NAV perspective is to take them down to zero because that minimizes the subjectivity. It’s challenging to value these companies. So, zero across the board is not the correct valuation because there is some value, even if it’s just option value, but it’s at least one way to minimize subjectivity.

It’s impossible to fund those companies just to ensure they are in good shape. After all, we don’t know when there’ll be any circumstances for those companies to get funding. So they need to stay alive or go out of business. So from a valuation perspective, I think it’s almost a complete lack of visibility.

A change of strategy for the emerging markets?

[00:02:16] Tilman Versch: Is there any lesson you’re taking from this? To reduce exposure further in some emerging markets and not invest in specific destinations anymore?

[00:02:26] Per Brilioth: No, not really. As much of a surprise, we certainly didn’t expect this to happen. And I don’t think many other people expected this to happen, even up to the Russian elite, which is very clear. As someone said, “This is not a war of the Russian people but a war of the top.” We announced an investment in Africa, which is also an emerging market. But we announced that just the other day, so we’re still active in those markets. I think this situation is pretty unique. And one can’t draw comparisons to other emerging markets in general.

I don’t think many other people expected this to happen, even up to the Russian elite, which is very clear. As someone said, “This is not a war of the Russian people but a war of the top.”

Consequences for other investments

[00:07:11] Tilman Versch: Moving away from the direct focus on Russia and Ukraine, what do you see as the indirect impact for the other portfolio companies you’re holding?

[00:07:25] Per Brilioth: So the situation there has direct and indirect consequences for the world economy because of its high energy prices. And that leads to, in one way, inflation, and then inflation leads traditionally to higher interest rates. And for long-duration assets, like the one we invest in, that has a negative effect which is higher than for short-duration assets. But then also, of course, higher energy prices worldwide put a damper on economic growth. Slow economic growth and high employment will get central banks to reduce interest rates.

So, this is a very fluid situation. So there’s that direct connection to it. And then, uncertainty on this kind of scale in the middle of Europe is something that’s not constructive for markets in general. We’ve seen markets we can measure from day to day. Public markets react with lots of volatility. Now, we know for sure that’s not going to last, but right now, that volatility remains. So both direct and indirect momentarily have at least consequences.

Higher energy prices worldwide put a damper on economic growth. Slow economic growth and high employment will get central banks to reduce interest rates. So, this is a very fluid situation. So there’s that direct connection to it.

Who is selling?

[00:09:00] Tilman Versch: Have you seen, if you can say there’s a certain outflow from the investor basis as well or another, like in disinterest in investments in Europe because you have a specific European exposure. And from an American perspective, Europe might be one of the scarier places in the world right now. Do you think so?

[00:09:27] Per Brilioth: I’m not sure, but we can measure. We’re not a fund, so we can’t measure outflows. But we see that the discount that we trade at has increased a lot. So, you know, more sellers than buyers for sure. It’s one way to look at it. So I guess that’s a reflection of the statement you’re making. It’s traditionally and historically that way, when uncertainty freezes.

And even before this Russia-Ukraine mess and tragedy that we’re in, we had sort of inflation, on the back of COVID, supply, etc. So you had these interest rates going up. But more importantly, you have the uncertainty of where interest rates would sort of level out, and that risk premium adds to the discount factor. So, but once you know, if interest rates are going to level out at two and a half percentage, or 3%, or whatever it is, then the risk premium comes down, and then that’s very constructive for assets like ours, for example, at least in the public markets or anywhere. I mean, if you look at this from a fundamental perspective.

But now, that risk premium has blown up again because of the uncertainty. So just from a fundamental perspective, I think that’s a clear way of looking at it. And that’s reflected in all sorts of assets being sold off, including our stock. Yeah, that’s the market for it. So that’s where it is right now. We believe very strongly in our NAV, the valuation of our NAV. And so, of course, that’s a big opportunity because the discount is very large.

Even before this Russia-Ukraine mess and tragedy that we’re in, we had inflation on the back of COVID, supply, etc. So you had these interest rates going up. But more importantly, you have the uncertainty of where interest rates would sort of level out, and that risk premium adds to the discount factor.

Impact on NAV

[00:11:31] Tilman Versch: In your NAV calculation, you have parts of market valuations also included in some of the calculations. Do they also impact the NAV for VNV Global?

[00:11:43] Per Brilioth: So we establish our NAV by taking the last transaction, as for where there is a recent transaction. That will take that price as the input for the NAV. And if there is no recent transaction, and we define recent by 12 months. We use a simple model, looking at a peer group from the listed world. And, of course, that peer group has in, you know, I think in pretty much every situation come in some way, come off, right?

Classifieds have come off a little less, but others, some tech companies, have come off maybe a little more than classified. So, we typically use a mix of classifieds, you know, the Ubers and delivery heroes of this world. Things that you can sort of getting relevance for our portfolio. And this is different from name to name in our portfolio. We’re just some kind of relevance sector-wise, but also business model-wise. There is seldom the ideal sort of a peer. But anyway, so as those have come off, then, of course, our models will show a lower price. So there is a link to the distant world in those modules.

We establish our NAV by taking the last transaction, where there is a recent transaction. That will take that price as the input for the NAV. And if there is no recent transaction, and we define recent by 12 months. We use a simple model, looking at a peer group from the listed world.

Valuations in the private vs the public world

[00:13:09] Tilman Versch: And do you see a general threat that while the venture capital world is still in a world of relatively higher valuations, when what you can get at the public market? Does that also have a ripple effect on the venture world at a certain point in time?

[00:13:26] Per Brilioth: Well, the private world is not as volatile on a short-term basis and not as volatile as the public world. And that’s a reflection also of that, at least for the better-run companies. They’re also better-run because they plan the liquidity well. So they don’t need to go to market and establish a price when the markets are the most volatile or the most uncertain. So you don’t get any pricing. Hence, less volatility in the listed world. It moves around a lot. The less well-run companies, of course, are also typically less well-run. They live because they can find funding in very, very open markets, for lack of a better word.

And when those markets are closed, these people have to fund themselves and then they have to fund themselves at a large discount. So they may be more volatile than public markets. But over time, the same company, private or public, should be worth the same multiple. With the same growth, same business model, etc. So there’s no question about that over time. I think that the fundamentals will prevail.

The private world is not as volatile on a short-term basis and not as volatile as the public world. And that’s a reflection also of that, at least for the better-run companies. They’re also better-run because they plan the liquidity well. So they don’t need to go to market and establish a price when the markets are the most volatile or the most uncertain.

And then, people like us invest for a 10-year period, so the volatility comes and goes, and you must be able to manage your liquidity and liquidity at your companies. And sometimes the public market goes down a bit, and sometimes they go up a bit. But I would also say that in the private markets, there’s still a lot of capital looking for deals, right?

Recently, we were looking at trying to get involved in a young company. And we were outbid by a double by someone. So there are still deals going on, and we still feel that risk appetite. And you can’t form a view from a sample of one. But the activity is not there. I think from our side, though, we have our liquidity. I’m very proud of the portfolio we have. Those companies are prepared for liquidity.

They have liquidity at some points you know, there will be funding needed. And when visibility into markets opening and closing is low, we are very mindful of that. So that we have the capital to support our own in these companies.

And so our activity goes down, but we have ample liquidity. So we can also do these if deals come along that are very attractive. But we always compare our investment activity to our stock price. And if we look at our own stock, and it trades at historically very, very high discounts to a price of our portfolio that we, in turn, think is attractive. We invest in it. We also buy back our own stock because it’s sometimes hard to find new investments that compare well to that opportunity.

People like us invest for a 10-year period, so the volatility comes and goes, and you have to be able to manage your liquidity, and liquidity at your companies.

We always compare our investment activity to our own stock price. And if we look at our own stock, and it trades at historically very, very high discounts to a price of our portfolio that we in turn think is attractive, right? We invest in it.

Investment breakdown

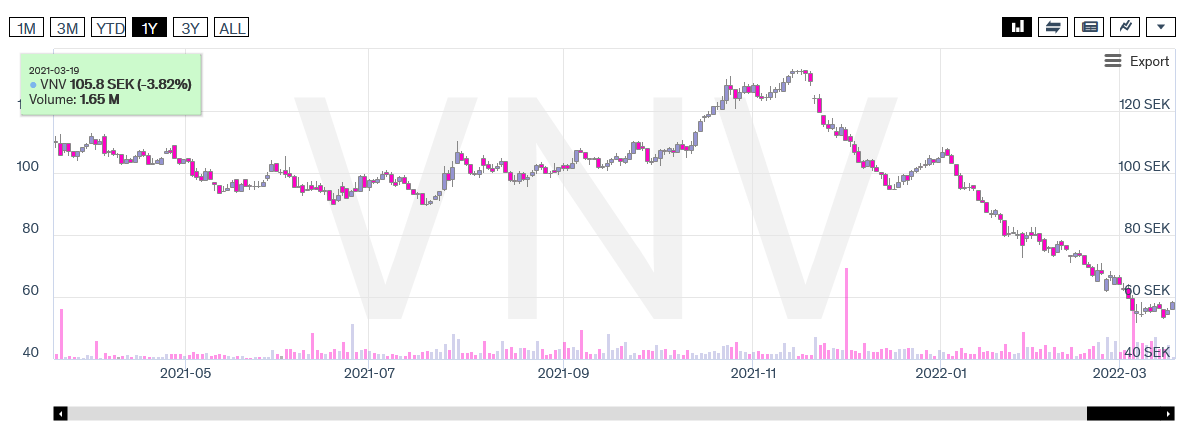

[00:17:11] Tilman Versch: Let’s use this opportunity to also add some qualitative data to the signaling you made to the market, because like, at the level of 120 the capital raise is on the way down to the level of 60-70. You were quite aggressive in stock buybacks, but lately, maybe, I didn’t get the emails correctly. But lately, you weren’t that aggressive in the level of a 50-55 with stock buybacks. And can you walk us a bit through your process of thinking about it, and how you acted there?

[00:17:47] Per Brilioth: Yeah, as I say, we always look at our own stock when we look at investments. And in the same way, we are opportunistic when we look at our new actual portfolio company investments. We’re also optimistic when it comes to our own buybacks. And as we sort of, started off with talking about Russia and Ukraine. This whole tragedy over there was not expected. If I had known about that, which I don’t think anyone did, right?

Then, of course, we should have waited, and instead of buying, whatever we bought at 60-70, buying it at 55 is better, of course. But we also must balance our liquidity so that we have the liquidity to support the companies in the portfolio. So it’s not even as much as I’d like to, and as an opportunity, it’s probably, it’s maybe unparalleled the risk-reward in our stock. But of course, we have to make sure that we can protect our ownership in the companies we have. Otherwise, that NAV will go down a lot. So it’s a balance always.

We also have to balance our liquidity so that we have the liquidity to support the companies in the portfolio.

We have to make sure that we can protect our ownership in the companies we have, otherwise that NAV will go down a lot. So it’s a balance always.

Are you turning into an “asset manager”?

[00:19:04] Audience question: I had this one question from a Twitter user who was interested in asking a question to you as well. It was a bit like, you already have this new setup where you’re not split off, or giving your shareholders the shares of companies you invested in, but you’re also now holding some of the shares.

I think Hemnet is a stake. Babylon is a stake. Swvl might get listed, and you hold a significant stake in them. They might also be in such crisis situations where you use these shares if they ask for consistent valuation as a currency to help other companies? Or what is your plan like? Is it more like you becoming a part private listed “asset manager”, and you hold companies for a while? And also, what is the plan there, and the flexibility do you have there in the current setup you have?

[00:20:04] Per Brilioth: You mean, in terms of us holding on to companies as they become listed?

[00:20:09] Tilman Versch: Like, you’ve changed a bit like this, this new line that you have listed assets also as part of VNV. You often like, before that, you rapidly gave them to shareholders or decided to sell? And now, you also have this opportunity. On top of this, you have a crisis, where you have some listed assets, and some private assets. And the question is if you balance between those opportunity sets, or what is the strategy with the listed assets?

[00:20:37] Per Brilioth: No, we don’t think about it like that. I mean, the listing is not a destination. We’re not a VC that will typically exit when things become listed. We can remain, shareholders when the company becomes listed. And in many of these cases in our portfolio, we will. That’s the way we do it. So, the first thing, I think the best way to think about our thinking, as things get listed is that one, we invest in private companies. We don’t invest in listed companies because we are listed ourselves, and we think that our shareholders can invest in listed companies themselves. But if our private companies become public, and become listed, we don’t have to sell them on day one.

The way we think about it is that if we are present on the company’s boards and remain very close to the conference, I think it’s a good way to describe it. We are, you know, we feel that that can add value for our shareholders, in that we have better visibility into the sort of the workings of the company. And that combined with us is seeing a return profile. That is 20% plus per year because that’s essentially our hurdle rate. We, you know, that combination allows us to stay as shareholders. But you could also argue them because we don’t invest in listed companies that did start, even if it’s a long-term exit phase.

Now Babylon, for example, I think we’ll hold on to for possibly like five years now. We have permanent capital, and hold on to it for a long time, because I think so strongly now. We’re close to the company. And we know the history, we know the people around it, and we have a much higher return profile than an annual 20%.

The way we think about it is that if we are present on the company’s boards and remain very close to the conference, I think it’s a good way to describe it. We are, you know, we feel that that can add value for our shareholders, in that we have better visibility into the sort of the workings of the company.

And in terms of managing the NAV discount by distributing listed assets, because that’s practically possible, right? That we have Mr. Gerald, we have people who are shareholders and listed assets like ours, so they can theoretically hold other listed assets. So, one way to reduce the discount is you distribute listed elements of the portfolio. Everything is on the table. We can do that. We have done that in the past, but not too astounding success if I’m very honest about it.

And I also think if we would have distributed Hemnet now, you know, some Swedish shareholders would love it, some American shareholders probably, maybe, maybe won’t. And the same goes for Babylon. If we distribute Babylon, as a US-listed stock, our American shareholders will probably hold it. Some Swedish pension funds have no mandate to hold American shares, so they would have to sell them. And we, for sure, do not think it’s the right decision to sell Babylon at this point. So, we don’t want to force that upon anyone. It’s better to hold it. Anyways, long-winded answer, I don’t know exactly if it covers what you were looking for.

And we, for sure, do not think it’s the right decision to sell Babylon at this point. So, we don’t want to force that upon anyone. long-termer to hold it.

[00:24:10] Tilman Versch: It helps to get an idea about your waiting process, what you factor in there, and how the decision is made? It’s more like, what we can do with the interview is to add qualitative data to the quantitative data points we get with news from your distribution lists and stuff like this.

[00:24:31] Per Brilioth: We don’t think about our portfolio that we should have 25% in listed assets and 25% in Swedish assets. It’s not the way we go about it. We go about looking for some optimistically very, very strong risk-reward opportunities across any stage of maturity in terms of capital raising.

Managing the portfolio

[00:024:56] Tilman Versch: Now, on this topic of portfolio construction, is there anything about trimming? Or is it just like you say, we are buy-and-hold investors? Or is there something in between?

[00:25:12] Per Brilioth: We have a very long-term view. So, when we invest, we don’t invest to sell after three years or four years. I think our colleagues in the VC industry, if the way they go about that, we say, we can get this return because we get paid if we get this return, and we get paid on exit. So, we won’t exist. That’s not the way this company or our incentive program works. So, we invest to hold it for ten years plus. We sell, the founders sell. So, I think that those degrees of freedom it’s the right way to invest, I think. But then there’s stuff in the portfolio that you know that we can sell. We have sold some Hemnet, and Hemnet has come off a little bit with everything else. Not so much, but I think that we have sold some, which is an indicator that is probably on the sell list.

So, we invest to hold it for 10 years plus. We sell, the founders sell. So, I think that those degrees of freedom, it’s the right way to invest.

We are not in a hurry because we have a lot of liquidity on the balance sheet. So that allows us to be price sensitive. I know that people buying Hemnet stock today are probably the best-classified investors in the world. I know some of them that I know are buying. And so that’s another good sign to see. So, to sort of not stress by selling that stock, it has very good risk-reward characteristics in it, even if they maybe don’t live up to a 20% annual return. You know, the downside is so low. So, risk-reward wise, it’s very attractive, and hence, we are not stressing to sell it.

I know that people buying Hemnet stock today are probably the best-classified investors in the world. I know some of them that I know are buying. And so that’s another good sign to see. So, to sort of not stress by selling that stock, it has very good risk-reward characteristics in it, even if they maybe don’t live up to a 20% annual return. You know, the downside is so low.

[00:27:06] Tilman Versch: Very interesting insight on this point.

Outlook on different portfolio companies

[00:27:08] Tilman Versch: If we look back at the last year, it was the year of companies becoming public. We had the SPAC topic; we have the IPO topic. Maybe walk us a bit through the current state. What has happened in the last year with your portfolio companies? And what will happen?

[00:27:31] Per Brilioth: Yeah. So, in turn, on the topic of listing, so pretty much exactly a year ago, Hemnet listed in an IPO here in Stockholm. It was only a secondary sell down. The company’s cash flow was positive and didn’t need to raise any funding. And then, during the autumn, we had the Babylon listed to us back. The start of public life for Babylon stock has been wobbly, to say the least. And there are some technicalities to that, which we can talk about. But in terms of going through the rest of the portfolio, we have Swvl, which looks to start trading on the 31st of March.

There’s a shareholder meeting on that merger and upon approval from that, we have every reason to believe that it will be approved. It will start trading in the US. And then the final one, which we did announce that it was going to try to enlist tourists back is getting but they also announced last week that they discontinue those ambitions to fund themselves to the stock market. Now, so they will then go to private markets, or to other public markets, the stock market has become a little complicated, and way to go to market.

And beyond that, we have two more companies, which are Voi and BlaBlaCar which have both been vocal in the press that they’re looking at IPOs. But we have yet to announce the final decision on whether that move is the way to go. So, I think that’s the entirety of our portfolio in terms of which ones are listed, and about to get listed or you know, have that in the pipeline in the near term.

In terms of going through the rest of the portfolio, we have Swvl, which looks to start trading on the 31st of March. There’s a shareholder meeting on that merger and upon approval from that, we have every reason to believe that it will be approved. It will start trading in the US.

Thoughts on SPAC listings

[00:29:48] Tilman Versch: These few months, or at least just one year of listing is maybe a too-small sample to ask this question. And you also have the long-term orientation as you said, but how happy are you with these listings? And it’s maybe, like what we saw last year with the SPAC. A bit of a premature form of listing if you look more on a long-term view.

[00:30:16] Per Brilioth: Yeah. It’s very rare that we very much advocate a listing. We think private markets work very well. There are some circumstances when the listing is good for a company’s strategy. Sometimes it’s for funding reasons that is the most efficient route to get funding valuation. And sometimes, like in the case of Babylon, it’s also their reasons which are more linked to the company sort of strategy versus counterparties, and customers, and branding, etc. So that was a strong reason why Babylon chose to list through SPAC.

And we can come back to that. But otherwise, the SPAC market, as such has become much more complicated over this past year, it’s always very much a capitalization form that was very populated by hedge funds, who are very interested in the optionality it gives you. You have an option on the upside but limited downside because you can always redeem your stock. And when the hedge fund world changed a bit, too, after GameStop, and after that, volatility started increasing in the summer.

Then also the financing part of the SPAC mergers changed a lot. So, like in the case of Babylon, there were so high redemptions. So, there was essentially no money left in the SPAC. Typically, you raise new money also in the listing like a normal IPO. And when you do a SPAC merger, so they did raise money through to what the SPAC world calls type, which is just a normal IPO money, but what then happened.

And this is not only relevant for Babylon, but also for pretty much all the SPACs that occurred during the autumn is that the remaining free float on day one is next to zero, because the only people who can trade the stock on day one is the people who were shareholders in the originally listed vehicle, the SPAC.

So, you have certainly no free float which is high enough to give you the kind of daily turnover, which large investors require to even do work on the stock. So, you have one set of shareholders that want to sell the stock because they want to get out, and you have no one else who can buy it because turnover is so low.

So, then you get in this sort of negative spiral which is a problem. And not only Babylon on the bottom, and just because we know it has been through, and that all others basically as well. I don’t think you find many SPACs at all that trade anywhere near their listing price. But it’s a technical issue. And if the companies do what they’re supposed to do, valuations will be set by fundamentals. Therefore, the SPAC routes to market have become less, less efficient, if you will.

Then also the financing part of the SPAC mergers changed a lot. So, like in the case of Babylon, there were so high redemptions. So, there was essentially no money left in the SPAC. Typically, you raise new money also in the listing like a normal IPO. And when you do a SPAC merger, so they did raise money through to what the SPAC world calls type, which is just a normal IPO money, but what then happened.

[00:34:02] Tilman Versch: If you can do any form of accounting on these observations you made with your companies, is it a net positive or net negative to do this listing?

[00:34:14] Per Brilioth: The market, it’s negative, right? And we have one SPAC, and that’s Babylon. It’s gone from ten dollars to five dollars, even to four and a half dollars, wherever it’s trading today, so down from that listing price. Thankfully, we’re not here to do investments for a few months. We’re here for a much, much longer time period, and so it’s really irritating, but it’s not it’s not super relevant. We’re not here to sell the stock at this price, we’re not here to sell the stock at double the price, and probably not a double or double again, right? So, we think that’s the potential.

But Babylon had a very valid reason to go to the SPAC market because, they are the leading sort of digital doctor in the world, right? In the true sense, it’s an AI platform, it’s not FaceTime, or it’s not soon with a doctor, it’s a real digital innovation in terms of the computer assuming the role of the doctor in a very efficient way. And the biggest market in the world, for health is the US. And the US market is different from our European markets. And insurance companies are a large part of that.

But in order to become a serious counterparty for the largest insurance companies in the US. They felt, and I think correctly, that they also decided to be listed in the US. So that instead of you being a British company, with some small, unknown Swedish shareholder, you are listed on the New York Stock Exchange. It becomes an easier counterparty to relate to if you’re a large US insurance company. At the same time, if you would go the IPO route to market, and in the US, it’s very clear, from your perspective, you could only talk about the history, and if Babylon could only then talk about an $8 million revenue from 2020.

And if you would even up those multiples to talk about that, then you will get the valuation which is not efficient. And what you will do then is you would resort to private markets where you can do an NDA with everyone. And you can talk about the projections for the future, and you get a valuation that reflects the future, not only the history, and in a sort of a company with this kind of growth, that’s mega important. But in the stock market, you can talk about the future, in contrast to the IPO market, so it becomes more similar to the private market with an NDA.

And so, they wanted to listen to us, the normal IPO market didn’t get them efficient capital raising. So, what was left was the SPAC market. And they took that, and then the SPAC market changed from their decision when they listed. In time we will look back on this and say, well, it was a short time it was trading like it wasn’t and I think it will have corrected to its proper value. As we go forward.

And if Babylon could then only talk about an $8 million revenue from 2020. And if you would even up those multiples to talk about that, then you will get the valuation which is not efficient. And what you will do then is you would resort to private markets where you can do an NDA with everyone. And you can talk about the projections for the future, and you get a valuation that reflects the future, not only the history, and in a sort of a company with this kind of growth, that’s mega important.

Babylon Health stock

[00:37:41] Tilman Versch: You mentioned you wanted to say something on technicality, but I think that’s already included in the points you said.

[00:37:49 Per Brilioth: Yes, technicalities around this free float mechanism, which just makes it a very, very hard stock to trade for large investors.

[0038:00 Tilman Versch: Then, let’s step a bit back and talk about the basics Babylon does. We did this already a bit, but what problems Babylon was solving? And how do they make money with it?

[00:38:16] Per Brilioth: Yeah, so Babylon product is a digital doctor. This is an AI platform which takes care of the patient, and the computer has access to so much data so it can check the symptoms and establish, like a diagnosis in a very efficient way. And the access to data makes the product efficient. And that, in turn, attracts more customers, which gets more data and makes the product more efficient. And you’re in this spin on network effects on what we look for. And so it’s a digital doctor in the true sense. And that’s attractive for the health sector overall because 80% of the costs in the health sector are people.

So, if you want to make health even more accessible, you have to make it cheaper. And if you want to make it cheaper, you have to do something with the cost base, which are 80% people. So, this becomes very clear from that perspective. That this is a product that, you know, gives you that leverage. Whereas if you know, a digital doctor, like a video call with the doctor doesn’t give you the same leverages. It’s more convenient for you and me because you’re the doctor and I’m the patient and you know, I can stay at home and you can stay at home, or we can still talk but still, an interaction like this still doesn’t do anything with a large hospital.

Babylon product is a digital doctor. This is an AI platform which takes care of the patient, and the computer has access to so much data so it can check the symptoms and establish, like a diagnosis in a very efficient way. And the access to data makes the product efficient. And that, in turn, attracts more customers, which gets more data and makes the product more efficient. And you’re in this spin on network effects on what we look for. And so, it’s a digital doctor in the true sense. And that’s attractive for the health sector overall because 80% of the costs in the health sector are people. So, if you want to make health even more accessible, you have to make it cheaper.

So that’s the basis of the product and the data, and then they commercialize this in different ways. So, you could say the traditional way, or these three ways of doing it, you know, the traditional. In the same way that you get paid per visit, you perform this in a similar sort of commercialization as the tele-doctors of the world. That one visit costs $40. And in some places, the company pays the 40 or $50, in some cases, the state pays it, or sometimes you’d pay to yourself. So that’s one way to do it.

The other way is that you white-label the software to the likes of insurance companies, and that revenue stream is like a soft product, or they call it AI as a service. And so, which has a very high margin, of course, and it’s an attractive product. But their big revenues today come from their third commercialization of this, which is to be part of the insurance mechanism in the US.

So, in the US, they have this concept of value-based care, a value-based care player is connected to the insurance industry in that they assume all the risks of the insured clients. And so, you go to the insurance company, you get insured, you pay your premium, the insurance company keeps maybe a 10% of that premium, and then gives 90% of the premium to the people that they outsource the risk to. So, this is the way it works. It has worked for a long time in the US. The traditional players in value-based care invest in brick-and-mortar hospitals, care stations, and doctors essentially, and they deliver products like this where they make single-digit margins on incomes.

Babylon who has of course done their layer on the digital product, the digital product can then sort out without any sort of incremental cost that is what exactly you need as the insured client to fix your problems. Whereas the traditional player must send you down to the hospital, which is very expensive. The digital player in Babylon’s case can decide that it’s only 10% that you need to go to the hospital, the rest we can take care of by the computer. So, it reduces the cost a lot. And then they can take that extra margin. So those are the three main mechanisms of how Babylon commercializes its AI product.

The traditional players in value-based care invest into brick-and-mortar hospitals, care stations, and doctors essentially, and they deliver products like this where they make single-digit margins on incomes. Babylon who has of course done their layer on the digital product, the digital product can then sort out without any sort of incremental cost that is what exactly you need as the insured client to fix your problems.

How can Babylon win in healthcare?

[00:42:58] Tilman Versch: But healthcare is a super tricky thing to do, right? Because if you mess it up, you can cause harm and damage to people, and you must make sure that you keep things safe and not lead to false diagnoses and advice, and if you do such a product software development, you know. It’s hard to make software that’s perfect from the beginning, you need the customer data. So, how’s Babylon going about this? And they were also like, if you dig a bit deeper into Babylon, they also cited quite vocal critics who attack Babylon that they lead to false diagnosis in the UK. How do you get confident that it isn’t running into problems?

[00:43:47] Per Brilioth: Yes, first and foremost, as you say, it takes a long time to build the product and gather enough data so that your AI platform can make an efficient sort of stand on diagnosis, essentially. So, in contrast to the tele-doctors of this world, which can basically, set up one day, buy some Google traffic, and have revenue the next day, this takes a long time to get any revenue.

I think in the case of Babylon, basically, it took them 5-6 years, before they have any meaningful revenue at all. It took 5-6 years to build the product, and gather data, so it takes much longer. But once you reach the state, you are in a much better position than the tele-docs of this world. There are no barriers to entry. You and I can set up a tele-doc today and launch it tomorrow.

In the case of Babylon, basically, it took them 5-6 years, before they have any meaningful revenue at all. It took 5-6 years to build the product, and gather data, so it takes much longer. But once you reach the state, you are in a much better position than the tele-docs of this world.

[00:44:42] Tilman Versch: I wouldn’t do it, I’m a bad doctor.

[00:44:45] Per Brilioth: I mean, hopefully, one of us is a doctor, right? But you get the point and so, in the case of Babylon, this is relevant for our entire portfolio of ours. This is sort of very, very true to network effects in general that it takes a long time to build enough liquidity or build enough data to have a product that you can commercialize. Because if you start to commercialize too early, you open the door for competition. But if you’re patient, you can start to commercialize from various to entry or high, and then no one can take over. But you’re right.

It takes a long time to build enough liquidity or build enough data to have a product that you can commercialize. Because if you start to commercialize too early, you open the door for competition. But if you’re patient, you can start to commercialize from various to entry or high, and then no one can take over.

So, one thing, it took a long time, because you must get it right. And their first client was the NHS in the UK. It’s one of the largest health providers in the world, obviously, state-funded but also inefficient. So, they were very keen on getting digital products into their system. But like in the UK or anywhere else, as you say, there’s a reason why the health sector is maybe the last large sector to digitalize because it’s different from country to country. And it’s something that can’t go wrong. If you order something from Zalando, the t-shirt comes in large, I wanted medium, we sent it back, it’s not the end of the world. But health can’t go wrong. So, it is problematic. And so, it’s the last one to digitalize. And NHS started with this. But it also becomes controversial, right? If you are a doctor in this world, you nearly assume godlike features, right? You can save people from sickness.

And if a digital product comes and takes away your godlike features, that’s controversial. It’s going to be controversial for years to come; it’s not going to be friction-free. And so, I think that’s the background to why there’s a lot of controversy around these products. And I think that will remain, but NHS as the first customer and a very politically sensitive customer was also very, very keen on trying to demonstrate to its population, the voters ultimately, that this was a product that works.

So, they did a lot of third-party studies, that this is a product that one, delivers the same sort of clinical efficiency as that of a normal doctor, and two, it has a cost that’s lower. And those third-party studies and services were very clear, right? That they were on par with a normal doctor, and sometimes also above and at a much lower cost. So yeah.

So they did a lot of third-party studies, that this is a product that one, delivers the same sort of clinical efficiency as that of a normal doctor, and two, it has a cost that’s lower.

AI’s challenges

[00:47:55] Tilman Versch: But looking into the AI divide, which must be done. If you think about Babylon. Also, AI is not like. It’s also not godlike. It’s filled with data from our real society, and it can also lead to racist outcomes. If you think about policing studies like that, it leads to people being identified as a risk or those who aren’t white. So, there are some outcomes in AI if you don’t take care that lead to certain outcomes, and it’s also like, hard to get AI, right? So, there’s also risk coming from this.

[00:48:31] Per Brilioth: Sure. I mean, you must be very mindful of that. Otherwise, you don’t have a product that you can use, essentially. But I think that in the case of Babylon, that’s why it took so long for them to sort of getting off the ground in terms of a product. And it’s by no means done, right? I mean, they have a product that’s viable; we look at who the customers are. They are the biggest sort of customers in the world, right? And so, they’re very grown up in their ability to be able to judge if this product is something we want to associate ourselves with or not.

So, they clearly have a product that’s viable. But it’s by no means done. I mean, there’s so much more to do. And it’s also a reflection that Babylon today has, you know. This year, they’re guiding for like a billion dollars in revenue. The US market alone is coming close to $900 billion for the markets that are relevant for them. So, this is still in the very early innings. I would argue that all that revenue will become in some way or form digitalized in time.

So, that’s also a reflection of that. There’s more to do, there’s more product development that you must do, and you must adapt as well because every country is different. And there will be different things to deal with as this market develops. I think Babylon has done that very well, right? They started in a very established health care market in the UK, they took it to a market where there was no pre-existing health infrastructure whatsoever in Rwanda. And then, they scaled it enormously quickly in Southeast Asia, and only that experience got them ready to go to the US. Because the US exists, maybe of all those three markets, within one market.

I think that in the case of Babylon, that’s why it took so long for them to sort of get off the ground in terms of a product. And it’s by no means done, right? I mean, they have a product that’s viable, we look at who the customers are. They are the biggest sort of customers in the world, right? And so, they’re very grown up in their ability to be able to judge if this product is something we want to associate ourselves with or not. So, they clearly have a product that’s viable.

Babylon’s acquisition strategy

[00:50:39] Tilman Versch: So, if I want to think about the strategy of Babylon, there is this maturity of product they are doing? They want to have data, this is their goal, and they want to build something on the data. So, in this line, if you think about the acquisitions they did in the US because they bought local care centers, they bought local places, the idea is to acquire those places and this customer context, to get more data and build a product on this, or how should I understand this?

[00:51:11] Per Brilioth: So, they’ve done different acquisitions, some acquisitions to buy existing value-based care contracts to get started quickly, which then connects them to a large population set, which has been served in a traditional way. And then they’re rolling out their product to them. Some acquisitions have been to increase the engagement, because in health care, overall, it becomes a lot about engagement. If you have clients and patients that are engaged, you know. Engaged when they are sick, and engaged when they are not sick, you can minimize the need for them to go to the hospital, which is the most expensive part of this making people healthy process. So, as so some acquisitions have been on this engagement issue.

It’s interesting on the engagement issue, in London, I think, don’t quote me on this, or I mean, I might get this somewhat wrong, but the big picture is if you want to go to the doctor, you wait for four or five days before you’re in front of the doctor. You know, in a normal situation. If you go to rural America, it’s one month. And so, imagine if you’re sick, and it takes one month to meet the doctor, how much sicker you become?

And if you can engage someone, that’s where the digital product becomes so efficient, right? If you can engage someone on day one, you can sort of sort out even in your home, what you need to do not to become as sick, as if you were told that in a month’s time. Hence, it has reduced the cost massively. So, there are lots of opportunities. Anyway, so the acquisitions, some of which are made to establish the presence and some to drive engagement.

Some acquisitions have been to increase the engagement, because in health care, overall, it becomes a lot about engagement. If you have clients and patients that are engaged, you know. Engaged when they are sick, and engaged when they are not sick, you can minimize the need for them to go to the hospital, which is the most expensive part of this making people healthy process. So, as so some acquisitions have been on this engagement issue.

Winning the US market

[00:53:17] Tilman Versch: How do we get the confidence if they are going to the US market where they haven’t had the experience? This market is quite a big opportunity, but if you just look at the opportunity, it might also be the chance that you are in acquisitions. And if some of the players want to sell something to you, or you ask them to sell something, it’s often not the best price you’re getting. How do you get the confidence as Babylon isn’t the [00:53:44 patsy] on the table, to say it in this picture?

[00:53:46] Per Brilioth: They rely on their experience from other markets, as we spoke about. Without that, there will be maybe a too risky venture to go into the US market without experience. And so, that’s the starting point. But of course, it’s a new market that requires new investments, new regulations, staffing, and some acquisitions. So, of course, it’s not one with zero risk, but the risk is very acceptable given the upside of the opportunity.

To our knowledge, and to what we can see, there is no one else who does this with the same sophistication with the same sort of broad product. There are people who do this in niche markets like maybe for diabetes only, or for this kind of cancer only, etc. But to be able to take on a normal healthy person, you have to do this in a very broad sense. And there’s no one else who does it in this way. There will be other supports, but the opportunity to become the largest and enhance the largest data set, we’ve spoken about how that all drives value, then the opportunity is probably now.

To our knowledge, and to what we can see, there is no one else who does this with the same sophistication with the same sort of broad product. There are people who do this in niche markets like maybe for diabetes only, or for this kind of cancer only, etc. But to be able to take on a normal healthy person, you have to do this in a very broad sense. And there’s no one else who does it in this way.

Measuring Babylon’s success

[00:55:26] Tilman Versch: So, what is your framework at VNV to track the success of Babylon? Like, what are your KPIs there?

[00:55:37] Per Brilioth: Well, there’s no single KPI that sort of stands out now. As you know, you may have listings per day in the classifieds. I think it comes down to the outlook for margin. This is a low-margin business that they’re getting into, and with the digital product, they will be able to take that to a very high model, in our view. We could be wrong. We don’t know the future. That’s the potential we believe.

And so, I think ultimately, it will be the margin on the contracts that they have. And those contracts are a few years old now, but it’s only with time that you can break them out and you can show that. And I think that’s also reflected in the share price today. The visibility into this is maybe low today, but then you also have enormous leverage as visibility into margin picking up on these increases. And it will increase if we’re right. It could be wrong for us. But I don’t think so.

I think it comes down to the outlook for margin. This is a low margin business that they’re getting into, and with the digital product, they will be able to take that to a very high model.

The future?

[00:56:45] Tilman Versch: Taking this 10-year outlook, you have or these five years, you already said these are two time periods. You already mentioned. What kind of company will Babylon then be? If things go the way you indicate?

[00:57:01] Per Brilioth: Well, I think it has the potential to be the global leader in this space. But now, since you and I spoke last, this company is listed in the US. So, I’ve had like a gazillion lawyers around, it’s just to say that I have to shut up about talking about the future of Babylon. So, I must be more mindful about getting into numbers and exactly what we expect, etc. If you look at the prospectus from the listing, they said $700 million this year. They’ve upped that to $2 billion; they said $1.5 billion next year. That’s pretty good to the extent that I am allowed to talk about it, but I really think it has the potential to become like the Amazon of digital health.

I think Babylon has the potential to be the global leader in this space.

Community Exclusive: Surprises in VNVs journey: VOI

[00:57:48] Tilman Versch: Quite interesting. Before we end our interview, I would like to talk a bit more about VNV, and the changes you make in your structure because a lot has happened. But before that, with this one-year timeframe, I want to give you a chance to tell a bit more about notable developments in the other portfolio companies since we’ve spoken. Is there anything that has surprised you? Is there anything that has an interesting story to tell? Is there anything that’s also a lesson you can learn to avoid future mistakes?

[00:58:23] Tilman Versch: Hey, Tilman here. I’m sure you’re curious about the answer to this question. But this answer is exclusive to the members of my community Good Investing Plus. Good investing Plus is a place where we help each other to get better as investors day by day. If you’re an ambitious, long-term-oriented investor that likes to share, please apply for Good Investing Plus. Just go to good-investing.net/plus. You can also find this link in the show notes. I’m waiting for your application. And without further ado, let’s go back to the conversation.

Without further ado, let’s go back to the conversation.

VOI’s innovations

[00:59:02] Tilman Versch: And also, the fascinating thing if you think about what kinds of technologies and cost aggressions allowed them to build the kinds of culture and the kind of networks they currently have, it’s fascinating. If you think about the culture along with the parts that are in it, that allows this kind of frictionless behavior.

[00:59:23] Per Brilioth: I know. Yeah, it’s fascinating! And moreover, fascinating that this is a 4-year-old company, but it’s only that old. I don’t know if we spoke about it last time, but that’s another thing. I’m fascinated by the subject that it’s so young, and it’s a thousand employees, and it basically runs infrastructure in 70 cities in Europe. It’s got tens of millions of dollars of revenue on a monthly basis, and it’s only a few years old. I’d spoken 10 years ago to look at a company that those revenues that it will be 10 years old, maybe 15 years old. And one factor is money; there has been accessing to money to build this. Money goes up and down, but equally important, it’s also a way to access technology.

And I speak to the guy who built the first classified site in the world some years ago now. He said, “when we built this is, what we did the first year is we carried servers up and down the stairs in the office building because there were no AWS. And there was no search engine. So, we had to spend, I don’t know, half a year building our own search engine. There is no assertion.”

Now, if you and I do it, we can have a contract with AWS in five minutes, and we can take you to know, off the shelf, a search engine in five minutes. So, it goes quickly, right? And that speed is not going away, even if money is tighter, maybe now. And the other one is, of course, a depth of talent. Like in Germany, certainly in Stockholm, Barcelona, and London. We typically talked about; we have grandchildren of Spotify already.

People who worked at Spotify left built a new company, sold that, and it’s now building another company, and they may be 30 years old. And with every iteration, they come with a lot of experience, right? How to build a team and what to think about the chapter? So it’s also that sort of entrepreneurial experience. Access to that entrepreneurial sort of experience is also very, very important in setting companies up quickly. So those are two points I usually make about our portfolio.

We have like 70 names, and 10 of them stand out, they’re so large in our portfolio. The other 60 are so small today. But this is the exact same way Voi was. When we had a veto, no one talked about Voi, it was tiny, but the tiny stuff in our portfolio, they will come out of the shadows of Babylon and become a large part of our portfolio. And it happened quickly as it did with Voi.

Access to entrepreneurial experience is also very, very important in setting companies up quickly. When we had a veto, no one talked about Voi, it was tiny, but the tiny stuff in our portfolio, they will come out of the shadows of Babylon and become a large part of our portfolio.

VOI’s strategy to become market leaders

[01:02:34] Tilman Versch: Do you think one factor might also be culture? Because, what I’ve heard about Voi, they started the latest in the market. They also have other brands or whatever, you name it, and they started the latest in many markets but now they are the market leader. What has influenced this and what cultural effects are you looking into?

[01:03:00] Per Brilioth: I think they were the first ones in Europe, right? They were the first to enter Europe, but they were quickly followed by Lime. And then after a while Tier came. But in terms of entry into some markets, they were not the first, but they have become the biggest or the second biggest in older markets. So even if they entered late into the actual markets, but as a company in Europe, they were the first ones out. It’s access to all these things. Technology, they have kept their supply chain working very well all throughout COVID, in contrast to the others, and then they’ve also found a way to run the operations of these companies because there is some operational stuff going on.

As you change batteries, and repair bikes. They come with an experience. I think pretty much all the founders came from the Swedish army. And they had sort of been brought up there. So, you can’t make mistakes. I think some of them have been in Afghanistan for a while. And they can’t make mistakes. You must be very, very diligent, and I think that’s helped them. Having operational excellence which is a big part of this. It’s not only an app but there’s also actually some real work going on the streets.

They come with an experience. I think pretty much all the founders came from the Swedish army. And they had sort of been brought up there. So, you can’t make mistakes. You must be very, very diligent, and I think that’s helped them.

New team members

[01:04:45] Tilman Versch: Yes, this was also one thing I was thinking about, I did my due diligence to better understand the company and maybe that’s the missing part. Thank you. Coming back to your structure in the way you want to keep operational excellence, you have grown your team significantly, maybe to lay the basics, who’s new on board? And what strength do they add to VNV?

[01:05:07] Per Brilioth: Yeah, we added four people now. In general, what we wanted to add is a diverse group of people around us to add to the capacity to do different things, to be present, and to be close to the companies without imposing ourselves. I think that’s where we are very careful not to impose ourselves because I feel very humbly that, who are we to sort of deciding on who, what, how these companies ought to be run. We take a lot of care to invest in founders and give them a large part of the upside or the equity in order for them to do their job well. So, we don’t need to impose ourselves.

What we typically say is that we are available on-demand for them if we can open up our network for them should they need help, etc. But we’ve found that it’s good to sort of be close to the company’s envoy, we’ve had one of our board members basically be part of the company for a long time. And, and I think that’s helped Voi in different decisions and stuff like that. But again, without imposing ourselves.

So now we have the capacity to be at many companies, and the portfolio has grown in a number of names. I think we’ve sort of added capital and become shareholders too. Many future potential voices. And, we have the capacity to be present in those companies now with these new two new teams of people. So, the team of people comes from different backgrounds. Well, you know, Dan Sanders, he used to work at Naspers for a long time and ran parts of OLX. So, he both has an investor hat on him. But he also has a capacity; he’s run large organizations within Naspers.

So, you know, as these companies grow, to be able to sort of accessing someone who has already run large organizations, I think it’s an asset to have within our team. Tessa has run her own start-ups. I think that’s a very important talent to have that we now have within ourselves because I don’t think any of our start-ups became many successes. But exactly because of that, know how hard it is and how difficult this is, and how much anguish you have when you make decisions. That’s very important. And on top of that, she has five years of experience in FJ labs.

So FJ Labs is an investor that’s run by Fabrice Grinda, which is next to Pierre Siri and is probably the father of classifieds. As we know it today, he built FJ labs. They may be made investments in 200 companies every year. So very young and they’re all network effects, all marketplaces, so exactly what we do, but on a global basis, so lots of experience from that. And then, Dennis, our third colleague, was part of the founding team at Voi. So, we got to know him there, and then BCG took hold of them for a couple of years. And now thankfully, we’ve moved in here, so it comes from a lot of capacity.

So, I mean, you know, from that background, and finally, Sasha Trofimov is the guy that we’ve known for, I think 15 years, he’s going to be present in our offices, Cyprus part of the portfolios in our separate company, so it’s important for us to have a presence there. But what he will help us with is to build the models that we use for our investment work and also for putting together our NAV also, he’s had a large, long experience of connecting with investors so he will beef up our IR capacity. So different things that we’ve added that we maybe have needed for some time that now’s the right time to add to the team.

We take a lot of care to invest into founders and give them a large part of the upside or the equity for them to do their job well. So, we don’t need to impose ourselves. What we typically say is that we are available on-demand for them if we can open our network for them should they need help. So, you know, as these companies grow, to be able to sort of access someone who has already run large organizations, I think it’s an asset to have within our team.

Growth and the corporate culture

[01:09:27] Tilman Versch: When I met you, I remember that I always get the feeling that you are quite an efficient guy and you like efficiency. And I also have this quote in mind, “you don’t want to manage people, you want to manage investments.” Yes. So how does this quote fit with this growth and the people around you? How does the corporate culture now change? How are you dealing with this?

[01:09:52] Per Brilioth: I’m super nervous. Yeah, no, it’s a good thing that these are people that we’ve known for a long time. And so, it’s, they know, the culture we have here, which is not one where we check if they come into the office exactly at eight o’clock and leave at five o’clock. The degree of freedom is high. And they know what we want to do. And, and so I hope, and I think it you know, it will not change that, that ambition of ours. But then of course Dan and Tessa sit in Amsterdam. So, I, Bjorn, and Dennis are here in Stockholm and all the others of course. But 2022, Slack, which you have here deep on my computer, I found out I closed it now. And Zoom, and it works pretty well.

[01:10:47] Tilman Versch: So, you have a certain notification that people are working on this interview. That’s good.

[01:10:52] Per Brilioth: Yes, exactly.

[01:10:54] Tilman Versch: So, I have done interviews with many investors over the years, and some of the investors have this idea of not hiring another person to be one-man jobs. To be focusing on the highly qualitative decisions and not like having this dilution, because you like someone, and he pitches so many ideas on you. You have so many ideas and I like the 10th idea, I’m not sure about it, but I say yes to it. Because it’s like if I say no to the person 10 times, I’d eventually have to say yes. How do you make sure that you have this culture that allows you to still have high-quality decisions and not dilute it by adding more exposure and adding more people?

[1:11:41] Per Brilioth: Yeah, ultimately it will come. I mean, I will still make decisions as we have before. And then what’s worked here with the small team that we’ve had, like [01:11:58 Bjorn] and some of the others they have, we have gotten to be so close to each other so that we know what will work and what won’t work here, basically. Therefore, I also feel that the new group of people, we’ve known for some time, so they should be able to morph into that kind of mentality as well.

And, you know, there are a million ways to run investments, but now, here, we run it like this. And then that’s the way it’s going to keep going. We will not be going to change how we run investments. And so, I think they already know what works here and what doesn’t. So, they can be efficient in their investments, sort of know what will I bring up? And what do I bring up? And then ultimately, sort of I’ll make the decision, or ultimately, I’ll decide what we suggest to our board, which is the Investment Committee.

There are a million ways to run investments, but now, here, we run it like this. And then that’s the way it’s going to keep going. We will not be going to change how we run investments. And so I think they already know what works here and what doesn’t. So they can be efficient in their investments, sort of know what will I bring up?

New horizons

[01:13:13] Tilman Versch: At the beginning of my questions, I was asking what strengths you add to the VNV with the new people? And you said this different experience on running start-ups and stuff like this. Are there any topics or themes you might have added? The new team members will broaden your investment horizon. It’s partly network effects. You have this network climate as one topic, which was quite a new investment theme. Is there anything that might surprise investors in the coming weeks or months with the African investment? I think you’re taking the first biggest step into Africa.

[01:13:53] Per Brilioth: Yeah, this is, this is other parts of Africa. We have, of course, been very active in the northern part of Africa. And a little bit in the most southern part of Africa, but not so in between, but yeah, you’re right. No, I think it’s more of the same. I don’t think there’s anything new really, the new people buy into what we do. I mean, they could have worked anywhere.

And I think we pay them, but if we pay them less probably what they would have gotten at other places. So, they really like what we already do. And they bring their experiences, they also bring, you know, we invest globally, and I think it’s good to have access to people who have a very global background. I mean, the Dutch people that we’ve already you know, the entire team that came back over this last that port, this entire thing that we brought on during the past five years, they have lived in Toronto, California, Buenos Aires, Cape Town, Dubai, New York, you know, it’s reflective of the kind of investment work we do, geography wise. So that’s good capacity.

But no, otherwise, when we’re here with network effects is what we do. And you might see us, as you alluded to, going into a network effect under other macro themes like there’s lots of stuff happening, which in some ways is associated with climate. But at the base, it’s still network effects.

I think it’s good to have access to people who have a very global background. And you might see us going into a network effect under other macro themes like there’s lots of stuff happening, which in some ways is associated with climate. But at the base, it’s still network effects.

Closing thoughts by Per

[01:15:37] Tilman Versch: Okay, quite interesting. I’m scrolling through my set of questions, but I think I’ve asked many. Is there anything you want to add as a point? We haven’t discussed thinking back through the interview. Do you want to go deeper into anything you want to add?

[01:15:59] Per Brilioth: Nothing springs to mind. We’ve talked about it a lot but no, I mean, there are 70 companies to talk about. I’m enthusiastic about every single one. We have one in Germany. Now, we have a few in Germany. But the new one in Germany is Surplus, which is a marketplace for recycled plastic, which we’re very enthusiastic about. A German guy used to run BlaBlaCar in Germany, actually. He started this company.

And it came through our scout network. So, as a scout, we have invested the first money and then we invested it, the second one is smaller than the portfolio. Anyway, there’s this kind of story behind every single one of these 70 investments. So, there’s a lot to talk about, we should talk maybe more often than once a year.

Staying optimistic during change

[01:16:58] Tilman Versch: We will figure this out then, when we stop the recording, I think, maybe with this kind of grim outlook that we have currently. The last few days, it changed a bit, but like me personally, and I’m not sure about you, if we looked at the interview from one year ago, it was lighter and easier. It was a tricky time.

But how do you keep your hope or optimism this time? And like how do you keep focused on the long-term view if this kind of turmoil has happened?

[01:17:31] Per Brilioth: Yeah, I know, this turmoil is deeply sort of saddening, the war in Europe, and also, you know, I’ve been looking at Russia for 30 years. And clearly, how we wind back the clock on that country so much, it’s a depressing sort of fact. And that’s going to affect us for a long time. But I think it’s important to know that every crisis feels completely new. And sort of, and I’ve been through many now, you know, especially being, you know, subjected to the markets that I’ve been subjected to, and in when you’re in the midst of it.

It’s very difficult to see how we will get out of this, and will ever anything ever become normal, but you can rest assured that it will become normal again. And so now we’re maybe in the mysteries, the visibility is so low, it’s very difficult, and it becomes we get down by it. But, you know, I think it’s also true that it’s always darkest just before dawn.

[1:18:44] Tilman Versch: But also, like normality might change a bit. So it’s quite interesting to see this is also a bit of change.

[1:18:51] Per Brilioth: The world changes, right? We must think more about the climate in the way the pandemic changed us, of course, this thing will change us as well. It’s quite as you know; normality will always change. But it doesn’t, you know, when you’re in the middle of the storm, it feels like it will change for the worse in a big way. And it will stay that way. I don’t think that necessarily has to be true.

[1:19:17] Tilman Versch: I think there might also be a chance for your portfolio and the exposure you’re currently having that some of the headwinds get stronger for some of the portfolio companies because they offer more efficient solutions. And like if you think about high gas prices and BlaBlaCar might be a call for them.

[1:19:39] Per Brilioth: High gas prices for BlaBlaCar is a big win, right? It’s much, much more expensive to now travel from Stuttgart to Berlin. If you can share the cost of this ride, then it’s good. So, now I think all our companies are involved in sort of solving big problems with a digital product. And that innovation is not going to stop; maybe it becomes a little bit less valuable in a period when interest rates go up. And there’s uncertainty, that the fact that this thing has to happen, and no doubt about it.

And if you invest for the long term, you know, if we’re right about picking the right digital products, then the value will be created a lot. As I say, we know these companies could be in a domain, even if the multiples should be the right multiples; we will produce our returns over time because the growth will be so high and because these products basically change large markets, and that’s what’s important.

So, now I think all our companies are involved in sort of solving big problems with a digital product. And that innovation is not going to stop.

Thank you & goodbye

[01:20:52] Tilman Versch: I think that’s a good point to close. Thank you very much for the time and thank you so much for the audience listening to Til here. Thank you very much and bye-bye, have a great week and the rest of the day. Bye.

Disclaimer

[01:21:06] Tilman Versch: As in every video. Also, here is the disclaimer. You can find the link to the disclaimer below in the show notes. The disclaimer says, “Always do your own work. What we’re doing here are no recommendations and no advice.” So please always do your own work. Thank you very much!