2G Energy is a German Mittelstand company that offers a solution for the Energiewende and European energy security. We had the chance to discuss the company’s technology with Friedrich Pehle.

We have discussed the following topics:

Check out Interactive Brokers

[00:00:00] Tilman Versch: This episode of Good Investing Talks is supported by Interactive Brokers. If you’re ever looking for a broker, Interactive Brokers is the place to go, I personally use their service because I think they have a great selection of stocks and markets you can access, they have super fair prices and a great tracking system to track your performance. If you want to try out the offer of Interactive Brokers and support my channel, please click on the link below. There you will be directed to Interactive Brokers and can get an idea what they offer for you. I really like their tool and it’s a high recommendation by me. And now, enjoy the video.

Who is Friedrich Pehle?

[00:00:38] Tilman Versch: Dear audience of Good Investing Talks, it’s great to have you back. Today, we are discussing the energy sector or the energy transitions, or as we Germans say, the Energiewende, because there’s a big shift happening in the way energy is produced in Europe and Germany. And today we have a guest from 2G energy, Friedrich Pehle. It’s great to have you here.

[00:01:02] Friedrich Pehle: Yeah. Hello. Thank you very much for inviting me. It’s indeed a very interesting issue which needs to be discussed definitely.

The energy landscape in Europe

[00:01:11] Tilman Versch: We will do a deep dive into what the company is doing and step-by-step also explain the product and what they’re planning to do, or where they’re planning to grow over the next years. But maybe let us start first with the whole topic of the so-called Energiewende, or the change of the energy landscape in Europe and Germany and also in other countries because we need to decarbonize worldwide. So Mr. Pehle, maybe you can explain a bit about what is happening in Europe and Germany, how is the energy landscape changing over the last decades?

[00:01:47] Friedrich Pehle: Yeah, specifically in Germany., we see that the energy sector is split up into much more participants. In former times, we had these large players such as RWE in Germany running large parts of the energy sector, Vattenfall and you name it. This has been liberalized. We saw a number of new players coming up, but I think the more important point is that for a number of years now, it’s become clear that the entire society needs to shift away from fossil-based and nuclear-based power production towards much more renewable power production. That has changed the basic assumptions of the entire process and the entire branch fundamentally. And a lot of new players came up, a number of new solutions came up.

And again, all this was shattered or was put under pressure on the 24th of February this year with the starting of the war in Ukraine and the intention of the European governments specifically, the German government; but the EU, as such, to become much more independent from Russian fossil energy supply.

For number of years now, it’s become clear that the entire society needs to shift away from fossil based and nuclear based power production towards much more renewable power production.

Politics and how it interacts with the energy market

[00:03:27] Tilman Versch: You already mentioned the war and politics. What role does politics play in the energy market?

[00:03:33] Friedrich Pehle: Basically, everywhere in the world, with very few exceptions, the energy market is highly protected or regulated by the relevant lawmaker. You always have books and a large list of regulations that need to be respected when feeding something into the energy grid, specifically electricity, but also other resources. In the United States, you even have 50 states of America, which are in energy respect less integrated than the EU, where the integration is much more forward than in the US. But the law and government plays always a role in the energy sector.

Why not wind and solar?

[00:04:37] Tilman Versch: So imagine an energy allocator in one country, you can pick it. And why should an energy allocator like someone who plans the future energy system, choose a combined heat and power engine, which is your product; we will go deeper into this in a few seconds, and not first and foremost, wind and solar. Why is your product a solution?

[00:05:01] Friedrich Pehle: A smart design for an energy sector would never decide to either or. He would always think of these two elements together and we feel ourselves with our products to be the backbone for the fluctuating wind and solar energy. We have prepared some analysis in former times, analyzing the actual weather situation; for example, in Germany, and the resulting production of electricity based on wind and solar, and the energy consumption. And found out that there are hundreds and thousands of hours during the year, specifically with misty autumn and winter weather, where the wind and solar energy is not delivering what is needed. And it would even be difficult to build more wind and solar plants to cover this, simply because if there is no wind in a winter night, then it doesn’t make sense to have another two or three hundred percent more windmills. If they don’t turn, you don’t get electricity.

So that means you need to have something for a compensation. Either storing electricity, which is then difficult and extremely expensive and basically not possible until today, large scale; or you need to have another source of electricity. Whereas CHP, which is based on a combustion engine, if it is then run by hydrogen and we will come back to it later definitely, then you have a kind of storage. Storing electricity from wind and solar in the form of hydrogen, which is then put into or brought into CHP.

Building the backbone for energy consumption

[00:07:15] Tilman Versch: You already mentioned the idea of the backbone and like the backbone market share, that’s like this backbone you described. How big should this be? How much of the energy market or how many of your combined heat and power engines do we need to fill this backbone function?

[00:07:38] Friedrich Pehle: Of course, it’s always a kind of network, but only to have some rough ideas. Germany is consuming around 500 terawatt hours of electricity annually. With a strong increasing tendency, should soon be at seven and eight hundred terawatt hours. Some people are saying it will also, within the next few years, be at 1000 terawatt hours and we have a number of days and nights. Hundreds of hours where wind and solar only deliver something like 1 or 2 percent of the nominal value. That means 98% needs to come from somewhere else. Either we have 50 times more windmills and solar panels than we need on normal days, which is completely impossible for physical reasons, and for acceptance reasons in society, but for many other reasons, or we need to compensate.

And there are experts saying, in principle, you need for every windmill and every solar panel, a kind of backbone compensating energy source for the moments, for the hours and days where the solar panel or the windmill is not delivering electricity. So maybe a hundred percent, as a mirror, is a bit too much, but it’s at least a very, very substantial part that is necessary. And not talking about the decarbonization of thermal energy, which is even much more important for Germany and for Europe, than the electrical sector.

There are experts saying, in principle, you need for every windmill and every solar panel, a kind of backbone compensating energy source for the moments, for the hours and days where the solar panel or the windmill is not delivering electricity.

2G Energy’s CHP explained

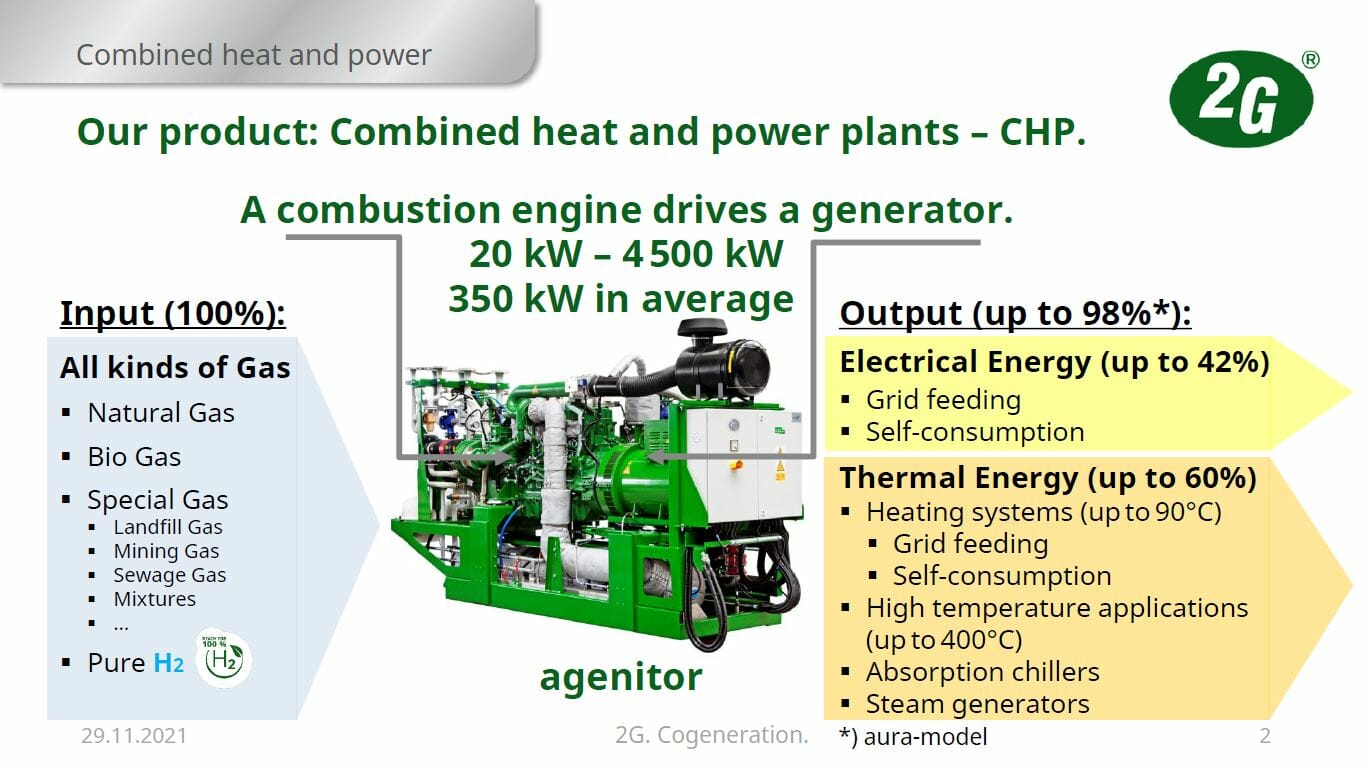

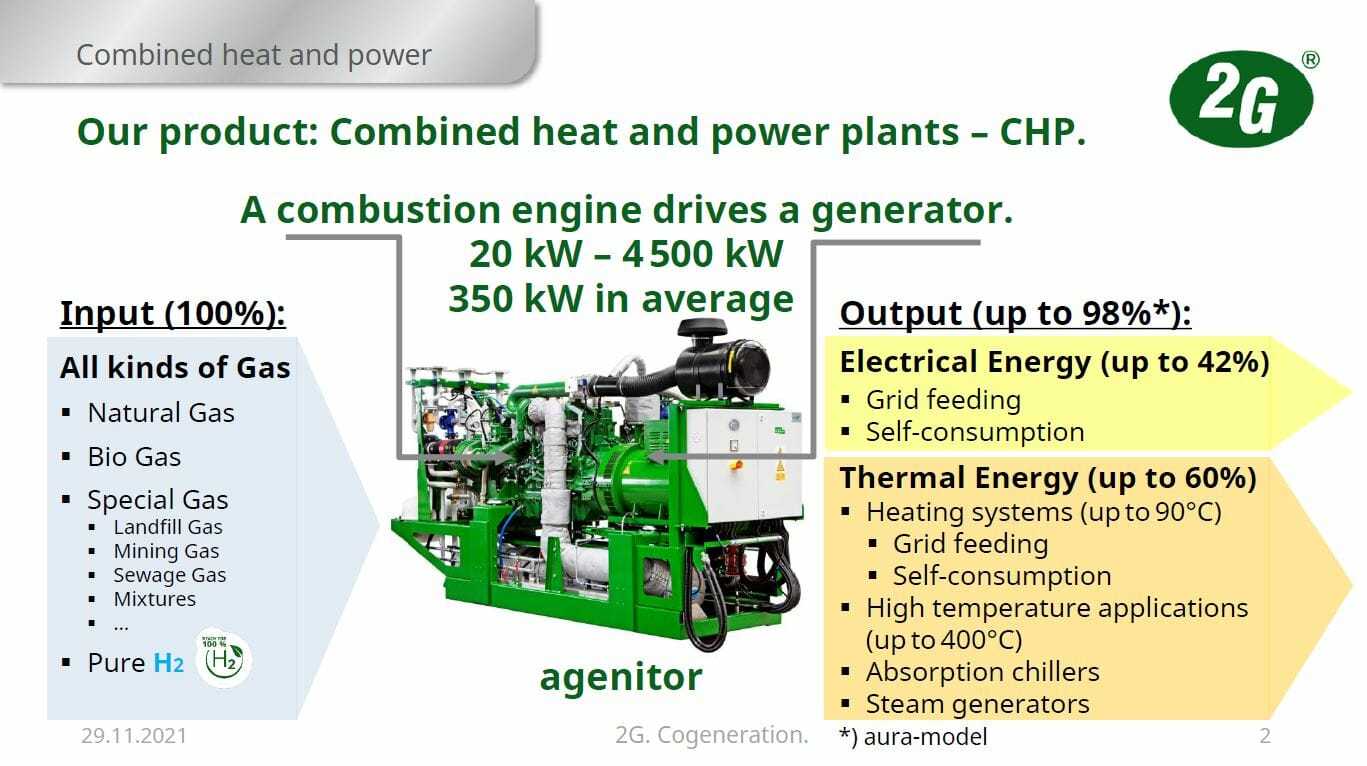

[00:09:26] Tilman Versch: So let us dive a bit deeper into your product, and we also have a chart here from one of your presentations. Can you explain your product a bit? What is this combined heat and power plant?

[00:09:40] Friedrich Pehle: What you see is the heart of a CHP. CHP is a bit more, what you see here is a combustion engine driving a generator. This combustion engine is driven based on gas, all kinds of gas. On the input side, we have natural gas, we have biogas, but also landfill gas sewage gas, gas for mines, flare gas, as well as hydrogen. So that’s on the input side and on the output side, we have achieved by the combination of using the electrical or the mechanical energy and the thermal energy, we have achieved overall efficiency far beyond 90%, which is extremely high, compared to basically all other ways of producing energy. And this electricity is fed either into a grid or is consumed on-site. That’s relatively easy, electricity is easy to handle in this respect.

More interesting is the thermal energy. The thermal energy can be fed into a grid again. Or it can be consumed on-site which is more challenging, and more demanding. We feel that we have a certain expertise in this. And that means we can change the thermal energy into the heating of buildings. That’s relatively easy. But also in the production of steam, as it is used in the hygiene sector of a hotel or a hospital or in food factories. Or we also have high-temperature applications up to 400 degrees for another more industrial usage. In this way, by combining electricity and thermal heat, we achieve this extraordinary high-efficiency level.

Efficiency of heat powering

[00:11:46] Tilman Versch: Maybe let’s go a bit on the heat side of the plant. What does the heat add for efficiency? So if it’s rightly used, on one side, you generate power; on the other side, you generate heat. How efficient can this plant be in combination of both energy and efficiency levels?

[00:12:07] Friedrich Pehle: As I said, we achieve or we exploit not always, but in many cases, more than 90% of the input energy. That means 92, 93, sometimes, even 94%. The key behind is you need to make use of the thermal energy in the perfect way. And also economically, you need to make use of it. Doesn’t help to have a super perfect CHP collecting all the thermal energy if you don’t have the real need in your factory or in your hotel afterward. That’s the key. The collected thermal energy in our CHP must definitely replace other thermal energy which has been produced in a traditional way.

The collected thermal energy in our CHP must definitely replace other thermal energy which has been produced in a traditional way.

Areas of demand for 2G Energy

[00:13:02] Tilman Versch: And which setup is an ideal setup to use a CHP? You already named some, but maybe you can make them clearer.

[00:13:10] Friedrich Pehle: The very typical is hospitals and food factories because they have a high need for electrical energy throughout the year as well as thermal energy. But with the increased prices in the energy sector, the price for electricity went up, but also, the price for thermal energy went up. So, we see more and more that people and decision-makers decide on a CHP in their factory, in the administration building. Although the CHP is only running during the healing period, meaning only three to four thousand hours or even less, that makes sense because energy is so expensive. Not only thermal energy but also electricity. That depreciation doesn’t play the same role as it did in the past and also the service does not play the same role in an isolated profit and loss statement of one single CHP. So, therefore, we see specifically, for the last three months, more and more CHPs to being implemented in a surrounding where it’s only running throughout the wintertime.

High energy prices as a revenue driver

[00:14:35] Tilman Versch: So, the higher energy prices and the high gas prices are drivers for your business?

[00:14:39] Friedrich Pehle: Yes, they are. Maybe I need to say, around 40% of our orders which we get is for engines which are designed or which are configurated, not designed; which are configurated for, as we call it, alternative gas which is not natural gas. And that makes sense that a customer who’s running this machine with biogas or with landfill gas is benefiting from high prices for electricity and thermal energy, because his input did not become more expensive, at least. Specifically, for agriculture biogas, we have to admit that agricultural biogas became more expensive in production. But all the other waste gas remain basically the same, whereas the output grew in money terms.

So that is for the 40%, but also for the 60%, which are natural gas machines, it’s very obvious that the profitability for customers is increasing. As I said, taking a very rough P&L, you have the cost and return for thermal energy and for electricity and gas, but you also have depreciation and service. And depreciation and service remain basically the same. And we have seen that the input costs have tripled over the last six months or so and the return as well in parallel. So service and depreciation are of minor importance these days and we see that profitability has doubled or tripled bottom line.

A customer who’s running this machine with a biogas or with landfill gas, is benefiting from high prices for electricity and thermal energy, because his input did not become more expensive, at least.

[00:16:39] Tilman Versch: That’s very interesting to hear and it’s a good tailwind for you. Do you want to add something to this point?

[00:16:49] Friedrich Pehle: In the last 10 years, we very often struggled when discussing with decision-makers in industry, specifically, that these companies were only interested in increasing their capacities. Cost-cutting was not on the agenda. So they asked if the payback time was beyond two years? No, then I will buy or spend my money on a new laser cutter, a new paint line, or whatever they had on their wish list. And cost-cutting, which is then our sector, was not an issue. Maybe ecological argument, reducing the CO2 footprint; but not cost saving. That was, in many cases, not the main driver on the agenda. That will change in the next two to three years due to the overall economic situation in Europe. We strongly believe that cost-cutting will be on the agenda definitely, very high, on top of it.

Handling different gases as energy input

[00:17:49] Tilman Versch: And also the switch in fuels may be, so let us talk a bit about the fuels you put in. So, there’s natural gas, biogas, and special gases. Are they different in handling and the way the engine has to be designed to use different gases?

[00:18:07] Friedrich Pehle: Yeah, in principle, we have a combustion engine. That means you bring the gas-air mixture into the cylinder and then there’s the explosion. For biogas and special gases, you need to have some processes in front to harmonize this gas, to have it as clean as necessary, and sometimes, also to blend it with natural gas in order to reach a minimum energy content. The main difference is when it comes to pure hydrogen because pure hydrogen is already explosive before it is mixed with air and before it is put under pressure. That means the one key is to bring the hydrogen into the cylinder separated from the air. In order to avoid that, if something goes wrong the entire engine explodes. So, it’s two ways to bring it in.

And that the second point is, that one target is to have an extremely clean burning process. That means you need to have a relatively cold burning process, which means you should avoid having one center flame, which is extremely hot. Because then you create CO2, then comes to nitrogen, Stickstoff, Stickoxid, as we say in German. You need to have a flame that starts immediately in the entire cylinder so that the average temperature is much lower. And then you have an almost perfectly clean burning process. So, these are the differences. Sometimes I’m asked about, does that mean that a hydrogen engine can also run with natural gas? Yes, it can run with natural gas. The difference is not as large as in the car industry as we have it with the different fuels which you can put into a car; that’s not the way. But it in our case, it would maybe be a bit expensive to take a relatively expensive hydrogen engine to let it run with natural gas. But in principle, it could work, yes.

Carbon neutrality

[00:20:35] Tilman Versch: So, the design of the engines, if you want to switch from natural gas to hydrogen, you’re offering both technologies. Like, to get carbon neutral, you have to upgrade the engine then.

[00:20:49] Friedrich Pehle: Yeah, exactly. And that is a very important aspect when talking about 2G as the technology leader in this sector. We are the only company that already today guarantees its customers that every nature gas machine in the power range of 100 to 1000 kilowatt can be modified from a nature gas machine into a hydrogen machine as soon as the customer wishes. It will take a week or so, three or four days. But if the customer one day gets access to a hydrogen pipeline, that’s important because otherwise logistic costs are simply too high. But if he gets access to cheap and reliable hydrogen, then we can modify this nature gas machine so that there’s no risk of ending up with a stranded investment saying, “okay, I have invested into a nature gas machine. But now, due to local law, I’m not allowed to let it run anymore.” Or I feel that I’m the last one, still working with the fossil engine, then we can modify. No risk.

We are the only company who already today guarantees its customers that every nature gas machine in the power range of 100 to 1000 kilowatt can be modified from a nature gas machine into a hydrogen machine as soon as the customer wishes.

[00:22:03] Tilman Versch: How much does this cost? Or like, how is this process, the upgrade?

[00:22:09] Friedrich Pehle: In a perfect world, we see that a normal nature gas engine lives for 60,000 hours, runs 60,000 hours. It’s basically eight to ten times more than a car engine. But after 30,000 hours, typically everything is removed from where the explosion takes place. Cylinder, cylinder heads, these kinds of things are taken away and new ones are put on the engine and this is the perfect point in time to replace the combustion chamber with a combustion chamber that is hydrogen ready.

And then we talk about 10 to 15 percent of extra cost, 10 to 15% of the basic investment to be cost in addition to have afterward, state-of-the-art hydrogen engine, which can then run another 30,000 hours. You can do it earlier. But that means that you take away the combustion engine, which is not yet at the end of your lifetime, but you can do it if that makes economical sense, or if for legal reasons, you need to do so, or for whatever ecological reasons, it is technically doable easily.

The production of the generators

[00:23:27] Tilman Versch: Okay. Then maybe let’s take a look again at the plant and maybe you can help me understand how you’re producing the plants and walk us through the production. So in which regions are you present and in which regions are you producing the plant?

[00:23:47] Friedrich Pehle: Let’s first talk about the production. We have one factory located in Northwest Germany, close to the Dutch border. We’re sitting in the neighborhood of Enschede but on the German side of the frontier of the border. And we are assembling the CHPs. That means we don’t have our own parts production. We buy all parts, we buy the engines, we buy the generators. Actually, we don’t buy the engine, we buy the raw engines and we put those parts on which we need because we have developed our own engines based on raw engines. We buy the containers, the cooler, everything. And that is then assembled in our buildings.

So looking into our production buildings, you will see nice, clean, assembly areas with heavy cranes; but basically, no parts production, no laser cutter, no, drilling, milling, and what else. Because we buy everything on the free market for many years. Above 1000 kilowatt, we buy even entire engines. Whereas below 1000 kilowatt, we buy the raw engines to make them high-end gasified stationary gas engines. The reason for that is that engines below 1000, by the rule of thumb, have been designed as diesel engines in the past. And then, in the second step, only been modified into a gas engine or gasified as we say. And that means that there are high potentials of doing it better, of having it these engines in a more specific way, have specific parts and components.

For the engines above 1000 kilowatt, this is not valid. These engines have been designed originally already as gas engines and much more difficult to find the potential to make these engines more efficient. We are working on it. So step by step, we have enlarged our own product range, so that we already reach 1000 kilowatt, but as I said, above 1000 kilowatt, we buy the engines. So, to summarize, one assembly process, one assembly factory here in Northwest Germany. And no intention to modify this because we fear the complexity which is linked in a second or third assembly factory.

When it comes to the sales process, Germany is our most important market, no doubt about it. Although we have to say that sales in foreign countries now, for the first time, have exceeded 100 million euros and the share of foreign markets is increasing steadily. It is still below 50% because we have a very large base of installed CHPs in Germany. And by this, we generate most of our sales in service in Germany. So very strong service business in Germany. Whereas in foreign countries, this is developing, simply for historical reasons. But when it comes to the order intake of machines, we see that in many quarters, the intake from foreign countries is above 50%. So, in this respect, Germany is losing a bit of importance, not because it’s shrinking, but simply because foreign markets are increasing faster than the German market.

[00:27:50] Tilman Versch: If you have capacity at hand and the customer calls and wants to order an engine or a plant, how much time does it take to deliver it?

[00:28:01] Friedrich Pehle: It very much depends on the question, whether it’s a highly tailor-made individual solution, so, there’s maybe a hotel with historical buildings, some difficult surrounding with extra requirements when it comes to the noise, this kind of things, then you are in a real project which needs to be designed. If you are looking for a standardized solution, says a CHP should be connected to a biogas factory where everything is well defined. Then we talk about delivery times of four to eight months. That means we still say to our customers, if you order now, we can guarantee you having the machine on the spot before Christmas; up and running from our side.

Supply chain issues

[00:29:09] Tilman Versch: You said you take a lot of raw materials or not raw materials, produced materials in and build them to the plant you want to design. Has this system been challenged by the supply chain issues we had, or are you still fine to stay with it and keep the system going?

[00:29:30] Friedrich Pehle: It has been challenged throughout the Covid-19 situation already. We are sourcing basically everything from Germany and its neighboring countries. So all the engines are coming from Central European countries, generators are coming from Central European countries, containers and basically everything. Nothing is coming from Russia. Nothing is coming from Ukraine. Very little is coming from Asia, mainly electronic components. But we are not in the same way exposed to these electronic components as others have been for two reasons. First of all, we are a relatively small consumer. We only need a few thousand microchips every year and not a hundred thousand. So we are anyway, forced by our customers to buy in large lots.

And, secondly, we are not that much exposed to price increases when it comes to electronic components, because the CHP has a limited number of microchips on board but they are not determining the price for the CHP; other than a PlayStation, or whatever you have in consumer electronics, or in modern battery-driven cars where you have hundreds and hundreds of microchips. That means we have been challenged in daily life, but all our supply chains, throughout the entire Covid-19 crisis, worked perfectly. Of course, with much more phoning around and sometimes paying something in addition. But at least the supply chains always remained intact. We have no customer who can seriously say in Europe that this project was postponed because 2G did not deliver the CHP as promised.

Of course, if the CHP was too late, but that was perfectly in line with the expectations of customers, because more than we are challenged, our customers are struggling on their construction sites; they have not prepared the construction sites in time. And therefore, we are pretty optimistic that our supply chain should continue to be reliable also within the next one or two years, which will be again challenging, no doubt about that. I mean, we all read newspapers, and we know what’s happening in the markets, but we remain optimistic that based on the experience of the last two years, our supply chain will also work the next two years.

We are not that much exposed to price increases when it comes to electronic components, because the CHP has a limited number of microchips on board but they are not determining the price for the CHP.

Community exclusive: Making mistakes in the project business

[00:32:35] Tilman Versch: So I think you have this 25 years of company experience like 2G Energy, you’ve not joined 2G in the recent years, but this 25 years of building experience comes with also an experience of making mistakes along the way and around the process. So, what have you learned over the years, what could go wrong in this kind of project business that you’re doing and how do you make sure to achieve very high quality?

Hey, Tilman here! I’m sure you’re curious about the answer to this question. But this answer is exclusive to the members of my community, Good Investing Plus.

Good Investing Plus is a place where we help each other day by day to get better as investors. If you are an ambitious, long-term-oriented investor that likes to share, please apply for Good Investing Plus. I’m waiting for your application.

Without further ado, let’s go back to the conversation.

Scaling up production at 2G Energy

[00:33:46] Tilman Versch: You’re planning to grow over the next years and so growing also for you means to scale up the physical production. How capital intense is this and how hard and easy is it to scale up your production?

[00:34:00] Friedrich Pehle: The limiting factor in production is definitely the availability of experts, of a well-trained workforce. And in our case, then also square meters, when it comes to the assembly buildings. For both scared resources, we intend to increase the net sales, the output per capita, per square meter by 10% year by year over the coming years. Still, we believe that, here and there, we need to add a new building in this industrial area and we are in discussion with neighbors and with the municipality, about how to manage it. But that’s a harder organic process, which will not end in an extraordinary high need for capital or funds. It will be also a process that takes place over a number of years so our very strong cash flow will help us to finance this.

The big difference is maybe the situation when looking at our service sector. Because we have calculated this; we see that the need for having varying parts and spare parts on stock, having it available will increase proportionally. That means, we cannot hope that the need for logistic space will only grow by also 10% or something like that over the next year. It will rather be 30-40% every year. Because of the complexity, and let’s say, the need of keeping these spare parts is not only for one or two years, it’s for 15-20 years, and that is a process, which is in the end, over proportional compared to the sales of machines. There we need to do something. We are currently investigating, but also there, we believe in the end, it will not mean that we have a need for capital from outside. To a large extent, it will be financed from our own cash flow.

Types of customers

[00:36:30] Tilman Versch: So after understanding your production, let’s take a look again at the customers. You already explained customer cases. Can you give me an idea of the range of customers? Like the smallest ones to the biggest organizations, you’re delivering CHPs?

[00:36:50] Friedrich Pehle: The smallest customer is maybe the owner of a small hotel or the facility manager of an administration building with something like 5,000 square meters. There we offer our 20 kilowatts, a so-called G box. That’s a small power plant far beyond the private sector or private housing. But as I said, for small hotels, old age pensioners homes and this kind of applications. Our largest engine is 4500 kilowatt. But we have realized a number of projects where we combine various engines together. So one nice project, which is also available on the Internet or in YouTube, was a hospital in the US, with 14 Megawatt, and 14,000 kilowatts. That is not an issue for the engine, it’s more an issue for the project management. Because of course again, complexity is increasing over proportionally, if we then combine various engines, in the way how thermal energy is needed within one project.

Future use cases

[00:38:16] Tilman Versch: In terms of product design and like, future use cases that aren’t really something that is material in your product pipeline, or your revenue pipeline, is there anything you’re thinking of? What could be future use cases for your technologies?

[00:38:34] Friedrich Pehle: We are not dreaming of having completely new applications. What we are fighting for is to get the right market share or the right attention when traditional fossil and nuclear power plants are shut down and to get parts of this market. I mean, when a nuclear power plant is shut down, this is such an immense market potential for us that we need to fight for it because it makes sense. So, we don’t see that completely new applications are coming in apart from this hydrogen. We are convinced that hydrogen will play a major role or the key role in the energy transition. And after the transition, in the normal running mode of the energy sector, when it comes to the misty and cloudy autumn and winter days. Then hydrogen will be key.

And there we are fighting and working for that, we will then play a major role in this. I mean, we are already definitely the technology leader in this sector. We were the first one to present a CHP fully driven by hydrogen and there’s no company in the world that has already such a comprehensive product range when it comes to hydrogen CHPs. And also, no company has already realized so many projects and has machines, CHPs, and engines in the field that are delivering electricity and thermal energy every day.

What we are fighting for is to get the right market share or the right attention when traditional fossil and nuclear power plants are shut down and to get parts of this market. We are convinced that hydrogen will play the major role or the key role in the energy transition.

Why a customer would choose 2G Energy

[00:40:38] Tilman Versch: Thinking about the decision-making process of the customer, you already mentioned that efficiency becomes a bigger and bigger role. Like, what is the decision-making process of a customer, and why are they deciding for you? And what arguments play a big role in this?

[00:40:54] Friedrich Pehle: We have to distinguish a bit in the old European countries, specifically in Germany, but also France. If the facility manager of the factory or hotel wants to have a new energy supply, be it because thermal energy is getting too expensive or too difficult, whatever. He will then turn to a kind of office of engineers and ask for a solution. And these engineers will always check the possibility of implementing a CHP. It’s part of their standard process. And very often, CHP is one of the various options. Seldom, it’s not an option. But by this, we come already on the long list of options and then we have to fight to come on the shortlist, and if we then can convince these engineers, then we will be the solution provider.

Outside the European countries, specifically in the US, it’s a bit different. There, our technology, the technology of combined heat and power is not a very well-known species, not in this containerized solution. The principle as such is, of course, well known, but there’s limited knowledge when it comes to the local applications as we deliver them. And there it’s necessary to get in contact with the decision-makers and make them aware of this highly efficient possibility of producing electricity and thermal energy.

In the end, if you succeed in convincing them, you have spent much more effort, but typically the customer will not say, “Okay, I understood. But now I will buy from your competitor because they are delivering it 2% cheaper than you are.” That’s the main difference, So more missionary work outside Europe, more explaining, but then a bit less pressure on price and in average, larger projects. As I said, the manager of a small hotel in the US will not easily switch over to a small CHP. It’s rather the hospital manager or the factory manager who decides for something like that.

So more missionary work outside Europe, more explaining, but then a bit less pressure on price and in average, larger projects.

Markets

[00:43:35] Tilman Versch: So how then have you built your market entries into another outside of core European geographies and how are your teams structured in these markets?

[00:43:44] Friedrich Pehle: Typically, we are focusing on the markets of G7 or other industrialized markets. We need high consumption of electricity, but we also need a stable legal framework. Even if we complain that there are so many papers to be prepared to connect an electricity production unit to the electricity grid, you still need this kind of administration. So, in countries where the administration is weak, typically also the network for electricity is weak. There’s a clear link. Good administration, and stable networks. Bad administration, and unstable networks.

And if you then have identified such countries, we travel around and look, for example, who is delivering the air conditioning for hospitals? Who has access to the facility manager of hospitals? Or are there say, production sites belonging to European groups, where we know that in Europe, they are already working with CHP so that the decision-makers are not completely astonished if they are contacted. So, these kinds of things, who have access to potential customers and then we team up with partners locally. Very typical that in remote markets, we find competent craftsman’s organization companies, 50-100 people or so, who have access to the customer group which we believe is of interest to us. And then we make a contract. We train them and do the sales process together. We don’t let them alone, but we need their market knowledge, and we also need them to build the service infrastructure, which is definitely necessary afterward.

We need high consumption of electricity, but we also need a stable legal framework. There’s a clear link. Good administration, stable networks. Bad administration, unstable networks.

New markets after the Ukraine war

[00:46:00] Tilman Versch: With the change after the Ukraine war, there was also a political shift in the energy security topics. Are there any markets that now have opened up for you as potential future markets with this shift?

[00:46:16] Friedrich Pehle: I would not say that specific markets have opened which were closed so far. Apart from the question that energy prices worldwide have increased, the importance of efficiency is getting more important as we discussed in the beginning already. But there is one feature that needs to be explained when it comes to our CHP. Typically, our CHP requires a connection to the electrical network; that has to do with synchronization.

Now it becomes a bit technical. Of course, you can drive a CHP on an island, a technical island, with no connections to the grid, but then you need to synchronize the CHP with all the consumers. That means when the consumption goes up, you need to make sure that the CHP is immediately running faster. And when consumption goes down, it needs to stop within seconds or reduce within seconds. So, it is possible; with digitization, this can be done. But to have such a feature costs money and in the past, we have seen that in Europe, the customers did not pay any extra money for this possibility to run your own electrical Island. It was clear that the CHP was always connected to the public grid and that is a clear indication that the decision makers had trust in the public grid.

It was not an issue to spend one or two percent of the investment sum on this possibility, in this potential of keeping your own electrical island; that has changed a bit. I’m not saying that suddenly 20 or 30% or 50% of our machines are now equipped with this additional add-on, but we see that interest is going up, that discussion around this technical feature is going up, and we believe that this becomes an… it is, I have to admit, nothing specific, also competitors have this feature. We are not the only ones. But your question was basically is there a change in customer behavior, and customer view due to political institutions? Yes, we see the beginning of a change. And we will be ready to answer this demand or to deliver for this demand.

In Europe, the customers did not pay any extra money for this possibility to run your own electrical Island. It was clear that the CHP were always connected to the public grid and that is a clear indication that the decision makers had trust into the public grid.

[00:48:57] Tilman Versch: And especially, if you think about Eastern Europe, they were, and are still highly dependent on energy from Russia, are they more interested in your solution now?

[00:49:08] Friedrich Pehle: In principle, we see that there is more activity in Eastern Europe or in Central Eastern Europe. Again, we need a stable law frame and without now saying, which state fits into this or not. But, of course, there are some states in Central Eastern Europe, where you have more trust in the legal framework than others. And there, we have seen also, prior to the events of the 24th of February, that the interest is increasing. But in principle, we see that also Eastern Europe is trying to make use of natural gas in a more efficient way than before.

Thought experiment: Competition

[00:50:00] Tilman Versch: Let us think a bit about competition. You already mentioned the competition a bit, but I want to make a thought experiment. Like, if Elon Musk decides tomorrow not to buy Twitter, but to go into the combined power and heat space and wants to invest there, where would it be easy? Like, where would it be possible to come close to you with a lot of capital and a huge workforce? And where would you be very relaxed and say you don’t have any fear of such a competition, in which expertise spaces?

[00:50:35] Friedrich Pehle: We see hydrogen to be the key to the future. We believe that a combustion engine based on hydrogen will play a much more important role in the future than the broad public today is aware of. And we believe that if the potential investor wants to spend awfully a lot of money, he will be consulted and will have consultants. He will understand that hydrogen is the key species, the name which you have mentioned, he will be aware that electricity cannot be stored only by traditional batteries but hydrogen is the key. So, either he spent awfully a lot of money in developing his own hydrogen competence or then it will kind of challenge for us, of course. Because then we suddenly have to fight against someone worth a hundred times more money than we have, a thousand times more money than we have, presumably. But at least, we can see it as a kind of confirmation, because that will be the way with hydrogen.

To make it a bit more realistic, the raw engines which we buy today and which we, to a certain extent, modify also into a hydrogen ready engine, they are coming from Liebherr. And Liebherr, the German-Swiss Earth-moving machine company, cranes, fridges, technology group with 10 billion euros net sales or so; they have officially stated that they stopped the production of gas engines and recommend to their customers that they should buy these engines from us. The learning point out of this is, that it is completely different if you produce tens and hundred thousand of diesel engines, that’s one technology. But to produce gasified engines is something else; not the production, but the development, is something else.

In former times, it was close to each other. But then these gas engines which were the result of this cooperation or combination had lousy efficiencies. We now have spent 15 years of development on increasing the efficiencies and we see that such an important player as Liebherr now says, “Okay, we stop the gasification of engines because we see it is not just a product which we can do en passant.” Either you do it properly with a lot of money and a team of engineers who really knows what they’re doing or there’s no chance to compete. So, therefore, would be interesting to see what Mr. Elon Musk could do with all his money and what his decision would be.

The learning point out of this is, it is completely different if you produce tens and hundred thousand of diesel engines, that’s one technology. But to produce gasified engines is something else; not the production, but the development, is something else.

Competition today

[00:54:00] Tilman Versch: But Liebherr is still supplying you with raw engines and you’re doing the upgrade for the gasified… okay. Then I better understand it. So the thought experiment with Elon Musk aside, who is your real competition at the moment and why are customers choosing you? Maybe we already had the hydrogen argument, but…

[00:54:26] Friedrich Pehle: Although we have to admit that most of our customers don’t have access to hydrogen and will not have it within the next two or three years. There are no statistics available. It’s not like the car industry or like the earthmoving machines industry, where you have perfect statistics for the entire Western world, that don’t exist. What does exist, there’s a statistic prepared by the German well-reputed magazine called Energy and Management, reflecting the installed power base annually for Germany. Germany is the most mature market, the oldest market, and the largest market for CHPs. So it’s still worth looking at these limited figures.

And looking at these figures, we see that there are two companies that have more CHP powerplants, or the power base is larger than what they have implemented. That’s Jenbacher from Austria and Caterpillar MWM in Germany. But for these two companies, you also have to say they deliver engines to other CHP producers. So, we buy a number of engines from Jenbacher. What I want to say about this, is there’s double counting in the statistics, they are definitely in place one and two, but their importance is maybe not as large as it looks. But on place three, you will find 2G Energy. We are basically the largest CHP producer in Germany, who is independent, not belonging to a large group; who’s completely independent, completely focusing on it.

And then you have another 25 companies following us. But there is extremely rapidly falling importance. So that means in Germany, we are the number three; number one and two, and four are engine producers, who have just one branch also producing CHPs for them. CHPs are only one way of bringing more engines into the field. We are the only one who is focusing on CHPs as core competence and have our own R&D when it comes to the engines. And why should a customer decide for us and not for number one, number two, or number four; Number four is, by the way, MTU, Rolls-Royce. These companies, the other three companies are coming from the serial production with thousands and thousands, in some cases, also ten thousand of engines every year.

As I said, for them, CHP is only another way of bringing more engines into the field. They don’t like these very specific applications. As I said, historical buildings somewhere in the inner city, where you have specific demands for everything, that’s not the thing that they like. These are not the projects they like. So if you have customers who have a specific need for the thermal applications and who feel that they have complex projects, and not just standard projects, they will rather turn to 2G than to this mass production company, Although their engines are also very nice.

If you have customers who have a specific need for the thermal applications and who feel that they have complex projects, and not just standard projects, they will rather turn to 2G than to this mass production companies,

Dealing with smaller players in the market

[00:58:15] Tilman Versch: You mentioned that there are a lot of smaller players around. Is it interesting for you to acquire some of them to consolidate the market?

[00:58:25] Friedrich Pehle: No, we are very, very reluctant because we believe that the smaller ones will disappear, not all, but many will disappear due to two reasons. One is emission. The emission requirements are increasing year by year. And second, also digitalization will be a major issue because all the efforts which you spend on digitalization need a certain base to distribute the cost. Otherwise, it becomes very expensive. But we are very, very reluctant of taking over a producer and continue with his products because this means an immediate increase in complexity. Maybe doubling the number of master data, although the top line only increased by, let’s say, 10 or 15 percent or so.

However, we have acquired a number of smaller service companies over the last 2-3 years. Service companies who have access to other brand name’s customer bases, who are doing the service for CHP, which have not been delivered by 2G. The reasoning behind this is that these CHPs which are serviced by our new affiliated companies, will come one day to an end physically and need to be replaced. In such a case, it is a very normal behavior pattern for the decision maker that he looks at the service and says, “Well, the old machine is gone but the service was done perfectly over the last 15 years. I first turned to my expert who is anyway coming every year, as doing a perfect job and ask him for his advice which CHP, which user should deliver the next CHP.” So, yeah, of course, we want to benefit from the fact that smaller CHP producers are disappearing, but not in the way of taking them over and increasing complexity, but by getting access to their customer base with the help of a well-done service, which is then done under another flag than 2G service…

[01:00:54] Tilman Versch: I’m not sure if you can disclose anything, but just like, at which rough multiples you’re buying such a service company?

[01:01:03] Friedrich Pehle: Not very high multiples; rather under average because we typically try to incentivize the former shareholder in the way that we let him participate in the success of the future. And there are very nice synergies. Typically, the net sales and profitability increase immediately after such a transaction. For example, because we have much better access to spare parts. We can guarantee spare parts prices which are typically, substantially better than what they formerly had. So that means that there’s a kind of win-win situation, but of course, the seller has to pay for this win-win situation, in the way that he does not get such a high price, he gets these benefits afterward by his share in the EBIT margin.

Lifetime of engines

[01:02:08] Tilman Versch: You already mentioned the lifetime of an engine. How should we think about the lifetime of the engine or a plant? How long does it operate? Is it like in years or…

[01:02:21] Friedrich Pehle: The engine typically has 60,000 hours. The surrounding CHP, the container, and all these pumps and coolers and whatever you have in connection with the CHP, their life depends very much on the annual running time of the CHP. That means if you only have 3000 hours because it’s only running in winter, the engine, then you have 20 years of lifetime, but then the CHP is over. Also, the container and everything else is over after 20 years. If you have a CHP connected to a food factory running 8000 hours so that the engine is at its end after less than nine years, the rest which is exposed to the weather, for example, is not yet at its end. So typically, in such cases, the engine is removed. Another engine is brought in, and then you have another ten years, so it depends on the application and the situation.

[01:03:29] Tilman Versch: What is the rough estimate of these two cases? Is it more like that you over time observe, like you have a lot of engines that are in the field that run for certain cases, like the foggy winter days, where it’s problematic, or is it a lot of engines that run like 24 hours a day?

[01:03:50] Friedrich Pehle: In the past, it was rather these 24 hours. Specifically, the biogas CHPs in the early phase. They were running 24/7 throughout the entire year, completely independent of what the demand for electricity was at that time. Simply because their impact was so marginal on the overall electricity production. There was no need. That means, in the beginning, we had a very, very high base of engines and customers with a very steady, high demand for service. That has changed. And it will change further. That means we believe that the sales of machines will increase over proportional compared to the service because running time will go down.

And in our outlook, in our guidance for the year 2024 and specifically for 2026, we say from 24 to 26, the EBIT margin will go down a bit slightly. The reason behind this is that the service will lose a bit of internal market share, simply because machines will run less time over the near future. So in the future, we will have much more machines running only 3000 hours compared to six or eight thousand hours and some will also only run 2000 hours especially if the energy prices remain such high or continue to grow.

2G Energy’s service business

[01:05:40] Tilman Versch: How does the service business work for you? Especially in Germany, where you have a dense network, you have different service stations and they are 2G energy workers and they drive around like from service to service job. Do you track the data from the machines directly? You can do a lot of remote work. Explain a bit the service business and the economics there also.

[01:06:05] Friedrich Pehle: In principle, we have a combination of our own service people and service providers. Specifically, in remote markets, we are heavily dependent on partners who can do the service. We cannot fly to Australia only to change the oil on the machine. So that means in the young markets, we have more service providers, and step by step, we have a kind of mixture of service providers and our own service forces. And specifically in Germany, Northwest Germany, our home turf, we have an extremely high density of own cars. They are either stationed here in Heek, in Northwest Germany, or in the backyard of the private home of the service technician himself.

We are collecting 100 million sensor data every week here on a central database. For many, many years, we collected these data already long before we were able to analyze them. Was a kind of a good smell that one day will become very valuable. And actually, 70% of the problems reported by the machines can be solved remotely. Only in around 30%, do we need to send a service technician physically on spot. We have tools in place to analyze this immense amount of data in a way that we try to do the service by anticipating the problems already when our technician is at the engine. So the perfect world would be that we can switch parts on the engine, although these parts seem to be perfect, knowing statistically that this part will come to its end within the next, I don’t know, 3 to 6 months or whatever.

We are not yet there. There are still some hurdles to be overcome but we are supporting our service planning substantially already with statistical data and analysis, which is not yet artificial intelligence. We are still following some algorithms to find these areas and these are algorithms that have been calculated or developed by the engineers and not by the machine itself. We believe that we can improve the efficiency of our service much more by exploiting these data. Again, an important advantage compared to all these smaller and minor competitors in the world who are still at the beginning of collecting data in the same way.

[01:09:43] Tilman Versch: How do you ensure in these remote, young markets that the quality of the service stays on a high level?

[01:09:52] Friedrich Pehle: We have our own department for quality checks when it comes to service. And secondly, within the hundred million sensor data every week, we get a clear understanding of whether the service was done properly or not. We can of course not control whether the service guy from the service provider has done it nicely, and cleaned everything afterward. If the customer finds black dots from the fingers everywhere, that’s something outside our centers. But whether the machine was done, or the service was done properly or not is something that we can easily read out of our data.

As I did not mention so far, within the Covid-19 crisis, we have implemented augmented reality tools, which allow us that the service is supported and even the initial commissioning of machines can be done by well-trained partners without having our own people physically. And that, of course, is also a way of controlling, especially when there’s one-to-one face-to-face cooperation, one expert sitting here in Germany and the other one working somewhere in Australia, for example, you can basically follow step-by-step and talk to each other and make sure that he’s doing things correctly.

How to make money in the energy industry

[01:11:33] Tilman Versch: That’s fivefold cost-savings. Coming to money, how are you earning money with a combined heat and power plant?

[01:11:48] Friedrich Pehle: As in other comparable companies, of course, we earn more money on service than on machines. The margin is double in service than in machines. But it’s very much comparable to other industries and other machine building companies, We earn on every CHP. We are not selling a CHP without earning a certain EBIT, at least in the planning. Of course, we have sometimes projects where in hindsight, we say,” Okay, we should have never signed the contract because things went wrong.” But in principle, the planning is that we should earn on each CHP which we deliver, or a certain margin, simply because in many cases, we cannot 100% be sure that the customer gets the service from us. There’s not a one-to-one connection.

If the customer wants, he can also buy the service on the free market, they might be lost. For some constellations, specifically for the engines between 100 and 1000 kilowatt, the customer is still depending on our spare parts, but behind 1000 kilowatts, he could also try to get the spare parts on the free market. At least, those spare parts connected to the combustion chamber, that’s where the most money is sitting.

Yeah, very important principle. We want to earn every CHP and we need to have a service that is competitive with the free service companies which are available on the market. Of course, we can ask for a certain premium, 10% more, something like that, but there are limitations. We cannot ask whatever we want. We are in daily competition with those delivering the service on the free market.

We want to earn on every CHP and we need to have a service which is competitive to the free service companies which are available on the market

[01:14:08] Tilman Versch: What is the recurring component of your revenue? Which are parts recurring on a yearly basis?

[01:14:17] Friedrich Pehle: In a model, you could say, if a CHP costs 100,000 euros, the customer wants to have the super gold, all-in service with everything, then he has to spend another 100,000 euros over the lifetime. Out of these 100,000 euros, parts would be 50% and labor 30%, and another is oil and lubrication 10 to 15%, something like that, around depending a bit on the model. But that indicates how much cost comes in addition to the investment over a lifetime and what this could potentially be recurring for us if we do it properly.

Customer retention

[01:15:12] Tilman Versch: In the recurring nature, you already explained a bit like this model you have with the boxes where the plant is in. So, if they run all the time, after 10 years, you could replace the inner boxes. And also, if you have plants that are after 20 years, you have to change the whole system. If you have these 25 years of experience, do you already have some data from customers that were with you over the 20 years or the 10 years, how much they tend to just stick with you, that you have after 10 or 5 till 20 years, that people tend to buy again with 2G energy?

[01:15:55] Friedrich Pehle: There’s a high tendency without now delivering a percentage point. But in normal cases, we should have a probability, which is definitely above 50% that we get the following order as well. But there’s no guarantee, definitely not.

[01:16:18] Tilman Versch: Do you have already data that pointed to this direction? Or is it just like that the fleet of plants is still there…

[01:16:28] Friedrich Pehle: The hard facts are a bit limited because we, of course, started with a low number of machines when we started the company. And that was primarily biogas in Northwest Germany. But based on this, those customers who bought 2G CHP in Northwest Germany will definitely have a strong tendency to come back to us again. Apart from that, many of our competitors of that time have disappeared over the last 25 years. We have definitely a higher market share today than we had 20 years ago.

The role of the service business in the future

[01:17:11] Tilman Versch: What role does service play in your revenue share in the future, what is your scenario with rolling out more and more plants, and what do you see over time?

[01:17:26] Friedrich Pehle: Yeah, as I said earlier, we believe that more and more of our future plants will have rather limited annual running time, maybe only running in winter and completely stopping in summer, for example. And therefore, we believe that on average, the service will be halved, at least on the individual machine. On the other side, we see that we will see more and more plants outside biogas installations, which is good news because those customers outside tend to not only buy the CHP, they also want to have a service contract over a lifetime because their controller before signing will always ask, “How much does a kilowatt-hour cost apart from the input gas; but all others, how much does that cost? He prefers to have a kind of guarantee.

That means we have two tendencies – one is reduced operating hours, which is bad for the sales of service. On the other hand, more customers asking for full-service contracts, specifically the farmers in the biogas factories. In the past, they are used to doing either part of the services themselves because they have combines and tractors, or at least to negotiate every time what it could be and not to be too much dependent on one supplier. And this is a customer group that is not growing as fast as the other customer group. I’m not saying that it’s shrinking, but the other customer group who wants to have a fixed calculation base, and who is ready to sign a contract for the entire lifetime or for a very long period; that group one is shrinking or the market internal share is shrinking and the other is growing.

So, we have in the end two tendencies. What does that mean in the end? We believe that we come a bit under pressure when it comes to the margin. But we believe it will only kind of marginal input… we have reduced our margin outlook from 10% to 9.25, which is, of course, a lot of money, which is in between, but it’s not a fundamental game changer.

[01:20:05] Tilman Versch: How long do you usually do service contracts? You said you have these farmers who just like if they have a service issue, they negotiate every time, but…

[01:20:18] Friedrich Pehle: We have some revolving service contracts, which are basically over a lifetime, or at least to the big steps, say 30,000 hours and then 60,000 hours. Others are for certain periods or a certain number of running hours. That’s very typical. But in tendency, it’s a relatively long part of the overall lifetime. However, the lifetime is not comparable to other products may be. So, when you take a lift to a hotel, for example, you put it in once, and then for the next 50 years, you will earn the service. That’s not the way. As I said, very often, after 10 years, the product is gone; latest, after 20 years. So, we always need to fight and struggle in a competitive way. Otherwise, sooner or later, our product base will shrink and by this, also the potential for service does not exist anymore.

Expected growth with Friedrich Pehle

[01:21:32] Tilman Versch: You’re planning for growth in the future years, like, what is the growth you expect over the coming years, and are there scenarios where you would need another capital raise?

[01:21:45] Friedrich Pehle: Our guidelines indicate 400 million euros net sales for the year 2026. This guideline is not brand-new. It has been issued before the inflation really took off. That means it’s basically one year old, these guidelines and needs to be revised sooner or later in the light of these strongly increased prices which we see also in our sector. But in principle, we believe that there’s a kind of volume increase of around 10% what we see, simply because it is a product which needs to be explained. It’s a quite complex sales process. So, therefore, might be a year where you have a bit more than 10% of volume growth, maybe a year, as we have seen in Covid, where something goes wrong, where you have a bit less. But around 10% is what we feel is the natural growth based on quantities.

And if so, we don’t believe that we need a capital increase. The good news is that globally, in our sector, customers tend to do prepayments when signing an order. So, we get around 25 to 30% from our customers when the customer signs the order and another 60% when the machine is ready for shipment. That means we collect, at least in the additional business, around 90% of the money prior to shipment of the machine. And that means with increased order intake, we typically also have nice cash in. And that’s why we are a bit reluctant to indicate that with strong order intake one day, we need to have capital increase to enlarge our production base and buy new factories or whatever.

Closing thoughts

[01:24:14] Tilman Versch: Thank you very much for these insights. For the last question of our interview, I want to give you the chance to add something we haven’t discussed. Is there anything you want to add for the end of the interview?

[01:24:26] Friedrich Pehle: Now, we have already mentioned all these issues. We believe that CHP as such will play a more important role than our audience will recognize today in media. People are talking about fuel cells about very fancy solutions. We read that combustion engines should be abolished, which is only the case for the mobility sector or for cars. not for the rest. We, as CHP producers, not only 2G, the entire industry is struggling a bit with this image of the combustion engine, which seems to be old-fashioned. But that’s not the case. A hydrogen-driven CHP has the same extremely low emissions that a fuel cell has. Therefore, it is often underestimated which important role this smaller CHP will play in the future energy transition.

We, as CHP producer, not only 2G, the entire industry is struggling a bit with this image of combustion engine, which seems to be old-fashioned. But that’s not the case. A hydrogen-driven CHP has the same extremely low emissions that a fuel cell has.

Thank you

[01:25:35] Tilman Versch: Thank you very much for your time. And thank you much to the audience for staying here.

[01:25:40] Friedrich Pehle: Yeah, it was a pleasure.

Disclaimer

[01:25:44] Tilman Versch: As in every video, also, here is the disclaimer. You can find a link to the disclaimer below in the show notes. The disclaimer says always do your own work. What we’re doing here are no recommendations and no advice. So please, always do your own work. Thank you very much.