In Juni 2021, I had the pleasure to discuss the history and potential of Gruppo Mutui Online with one of the founders of the company, Marco Pescarmona. Here you can enjoy the transcript.

We have discussed the following topics:

- Introduction

- The challenging first years

- Doing business in Italy

- Starting new business angles in Gruppo Mutui Online

- The divisions within Gruppo Mutui Online

- The founders

- Time management

- Would he sell his share in the company?

- Going public with Gruppo Mutui Online

- Dividends or buybacks?

- Debt at Gruppo Mutui Online

- Expansion strategies

- Synergies

- Gruppo Mutui Online’s clients

- Maintaining high quality

- Thought experiment: reducing to 3 promising businesses

- Risk and reward

- Challenges in broking

- Effects of regulation

- Future plans

- Marco Pescarmona on Dealing with competition

- Dealing with big players like Google

- Characteristics of the Italian market

- The impact of Covid

- Pressure after the good performance in 2020?

- The outlook with Marco Pescarmona

- Maintaining a feeling of familiarity in a growing company

- Goodbye

- Disclaimer

Introduction

[00:00:00] Tilman Versch: Hello Marco, it’s great to have you on from Italy. How are you doing today?

[00:00:06] Marco Pescarmona: I’m doing pretty well, thank you.

The challenging first years

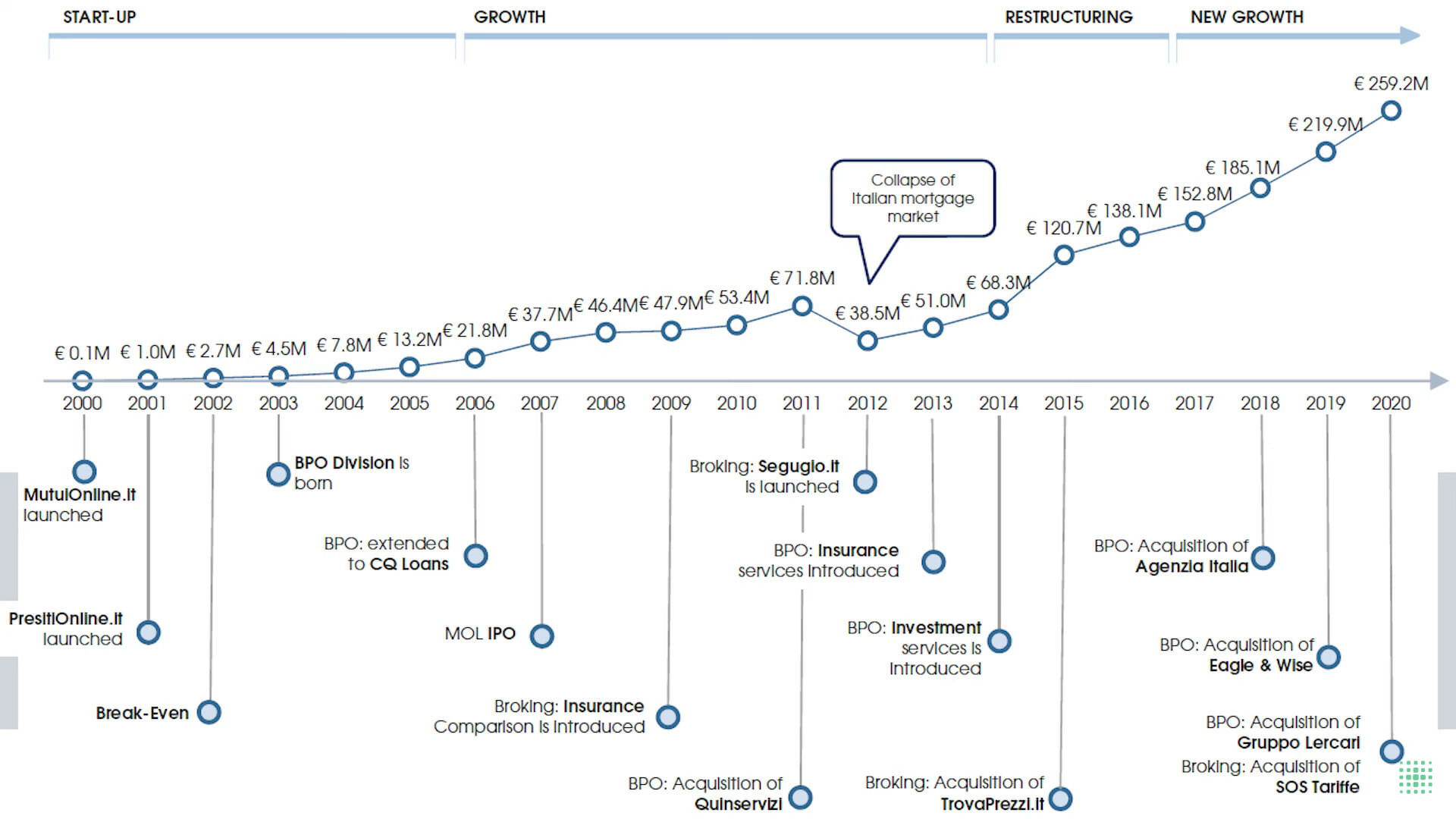

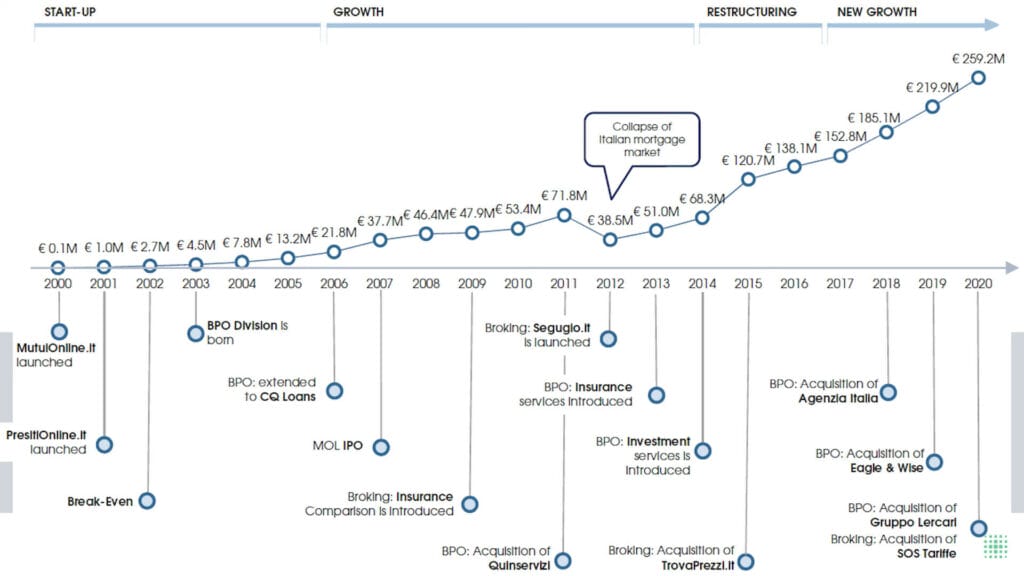

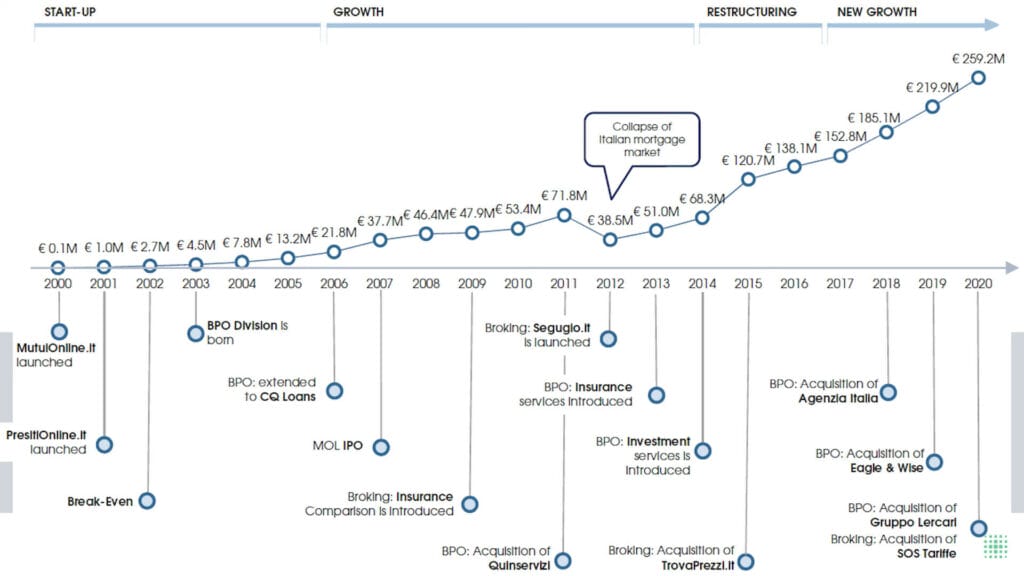

[00:01:10] Tilman Versch: I want to start with a nice chart I get from your investors’ presentation, it had the major milestones you had in the company. This is the one chart you give from your investors’ presentation, and it shows the milestones and the success you have. But talking about successes is also a bit boring, so I want to start with this question: what were the crisis setbacks and the problems you experienced building your business like this?

[00:01:19] Marco Pescarmona: Well, we had a good number of them. Actually, we got into a crisis right after we started, because we set up the business and launched it in the year 2000. It was the final year of what they later called the internet bubble. It was very easy for us, in fact, to raise money to start the project. And then, while we were working fourteen hours a day on building the company not really worrying too much about raising the next funding, all of a sudden, the internet bubble burst, and it was impossible for quite a while to raise money for this type of activity. That almost killed us between the end of 2000 and 2001. So, the first thing that we suffered was the fact that we were an internet business at the wrong moment, then we managed with a lot of effort to raise some money by delivering a very strong performance with a lot of work and then we survived.

But then we got into the subprime crisis in 2008: right after our IPO, we were meeting investors and they were all asking questions about mortgages, and if we had problems, they were asking for their particular concerns about mortgages. For a while it was ok, and we had a reasonable period for a year after our IPO, but then, all of a sudden, the mortgage crisis became apparent and nobody would even want to talk to a company that had to do with mortgages, which was our main business. We couldn’t even get meetings with investors because they thought that anything that had to do with mortgages was risky, that was what was taking down the American financial system. So again, we had problems, and also our main clients, the lenders, had problems at the time, so we had difficulties, especially on our BPO side.

And finally, the third crisis – because you know, you always have three after two – basically it was the Southern European sovereign cress when…that was actually probably comparable to 2000 for us because it was a very serious threat to our business. At the time we were still doing lending and mostly mortgages and all of a sudden all the Italian banks between 2011 and 2012 could no longer fund themselves on the markets, even the Italian State had very serious issues, and from 2011 to 2012 our main reference market (which is the Italian residential mortgage market) declined by two thirds, so from one year to the next, you lose two-thirds of your market and your revenues. Therefore, especially for the BPO business which was fixed-costs-based, this was a nightmare, but it was a nightmare in general across the board.

So basically, every part of our DNA got into a crisis: first the internet (Mutui online is online mortgages), then the mortgages, and finally the fact that we were Italian. So these were the three toughest moments in our existence.

Doing business in Italy

[00:05:26] Tilman Versch: Let’s go back to the fact that you’re Italian and from a German audience you might have to feel something like 2012, the Euro crisis and the mortgage market collapsed again in Italy, or is there something that structurally changed in the last years?

[00:05:46] Marco Pescarmona: Well, there are two answers to this. One is about the country and the general situation and the second is about ourselves.

Let’s start with the second part. From our point of view, even if we were to go through a 2002-like crisis, we are much stronger than years ago. We are, in particular, much more diversified, so we have businesses that are less subject to such a situation (like insurance broking or e-commerce price comparison, utility intermediation), and also on the BPO side a lot of the businesses are more or less independent of the credit cycle (I’m talking about claims adjustment, or vehicle fleet management, the leasing and so on). So, the business itself would stand much better a similar type of crisis, which by the way also generated a lot of opportunities (it was not only bad, it was a time when we could buy very nice businesses for a little, not only in Italy), so we are stronger to withstand something like that.

The first part of the answer is that we don’t think it’s very likely that something like that will happen again, and that’s for a number of reasons. I would say there is clearly a much greater level of economic integration in Europe, so the idea (which was already a bit absorbed at the time) that Italy could be let collapse is much less likely. The monetary framework is such that it supports the Italian sovereign bond issues, it supports the Italian banking system, and the banking system is a bit more decoupled from the state. Also, I think that everything that is happening now with the recovery plans, the pandemic recovery plans, is also quite positive because these recovery plans are basically forcing local governments to undertake a set of reforms that are very useful for the country that they wouldn’t have the political ability to pass autonomously because of a lot of particular interests. So basically, also in terms of increasing the efficiency of the public administration, the court system, all the things that are not working perfectly well in Italy…I think that having these plans brings much more authority to the governments to drive the change.

So, I think it’s a very healthy situation overall, it’s not good that we needed the pandemic for these, but I think it was a powerful catalyst for change. Again, I think we could have recessions, I think we could have maybe a slow recovery, I don’t know that, but I think it’s very unlikely that Italy – both because Italy has done and will be doing a lot of things but also because the European framework has more cohesion – it’s very unlikely that Italy will be subject to a sovereign risk like the one we saw in 2012 for the next ten years.

Starting new business angles in Gruppo Mutui Online

[00:10:03] Tilman Versch: Let’s go to the lower end of the screen I shared with you. Under the line, you see that a lot of businesses were either built by you or held by you. How do you get the idea of starting such a new business before you decide to buy or build, what is the common ground there?

[00:10:27] Marco Pescarmona: In general, our preference is for creating new business. We see ourselves as entrepreneurs and creators, not only myself and Alex, but I would say the company, the group. So, our preference is for finding opportunities that are just not exploited, that are maybe needs of customers, clients, or potential clients, and we try to solve them. We operate in the service sector and mostly in financial services, and we think that there are a number of situations like that. As you learn more and also as the situation evolves, you keep identifying opportunities.

The best and where you create the highest value, we think, is finding a need and trying to build something that solves the need, that creates value or efficiency, or is a better way of doing something, and then you grow that business. If the opportunities are there (you don’t always get it right…) and you execute correctly, you might end up being the leader of possibly even a sizeable business without having to invest too much. All our businesses are mostly constrained by execution, not by capital, so it’s not a matter of the cost of doing things, it’s a matter of getting the right idea and executing on that idea. That’s in general our preference, but obviously, that doesn’t always work.

The best and where you create the highest value, we think, is finding a need and trying to build something that solves the need, that creates value or efficiency, or is a better way of doing something, and then you grow that business.

Also, it’s a slow process, but we are not worried about that: we do things for the long term, and we know what we are starting today will bring fruits in five years maybe or longer, it depends. At the same time, we realize that – this is what we did for the first ten years of our life, we did everything internally and for quite a long period we didn’t even consider the possibility of doing acquisitions – then we realized, also thanks to the financial crisis of 2009 and more importantly 2012, that we could do acquisitions.

Then we started doing them also to accelerate the diversification, because the thought in 2012 was: “Look, we are in a difficult situation, we intervene to keep the company floating and making some money, but” we said, “we want to be in a position to do ok and to go again even if the situation doesn’t recover, even if the worst happens.”. And so, we thought: “We have some money in the bank, there are some companies we understand and that are close to what we do: let’s try to do some transactions”.

We realized that we were also able to generate some value in that way because especially the first things we did were good experiences. And so, we realized that if we could acquire businesses that were either synergies or that we knew how to run better or that commercially would fit better (and again, that’s a synergy) within our portfolio, it could make sense to bring them within the group. Of course, always with a lot of discipline on what we were willing to pay for the acquisitions.

In fact, we also realized that – and this is quite important – in many of the businesses in which we are present there are barriers to entry, both our broking division operates in businesses with barriers to entry and the same is true for our BPO division, which means that in many cases the market leader has very strong and defensible position if the execution is reasonable. So when we have the opportunity to acquire a market-leading business in a niche that is coherent with the activity of our broking division or BPO division, that makes a lot of sense, and we know that in those situations where there is already a strong player we wouldn’t have a very strong chance of building a very strong position in the same business. So also growing with acquisition is a good strategy and is complementary to what we did in terms of organic things. And also, it’s one of the few ways we can deploy capital effectively because internal reinvestment opportunities are limited.

Growing with acquisition is a good strategy and is complementary to what we did in terms of organic things. And also, it’s one of the few ways we can deploy capital.

[00:15:49] Tilman Versch: You said something about identifying the needs, that I think is more kind of an art than a science where you have clear rules. How are you going about identifying the needs of customers? Do you look at what others are doing in different countries? Do you do deep surveys? How are you going about that?

[00:16:10] Marco Pescarmona: Well, you’re right it’s more an art, at least for us professionals. Basically, you need to learn, sometimes in detail, the workings of a particular market, a deep knowledge of what either the customer (if it’s a consumer) or a financial institution needs or could need, maybe they don’t even know they need it, but, you know, finding a problem…again, by knowing exactly how things work, even trying it yourself, or thinking about how they could work better is one way.

The problem is quite often not only finding a theoretical need, but figuring out whether a solution, the solution that you could – there’s also a creative part, because finding the best mortgage for me at the best possible rates, and that was one of the things that we identified at the very beginning, and then how you deliver on that? It could be an online comparison-based broker, or it could be a completely different thing…so there is also a lot of variation on the solutions, that are also quite creative. Figuring out whether the solution will work commercially in practice is not always obvious: there are things that you think will be killer solutions and there is in the end no consumer demand. For instance, we tried over the years the comparison of bank accounts, and it turns out that, despite that everybody has a bank account and we are the leader in this specific business, it’s tiny and it doesn’t really become any bigger, it always remains marginal, while the same concept for other products is a very big business. So those two things are important.

Figuring out whether the solution will work commercially in practice is not always obvious: there are things that you think will be killer solutions and there is at the end no consumer demand.

In terms of tools, I think we started to use more tools like focus groups, hiring companies that will do research on particular things, etc, but it is more a way to confirm ideas than anything. And of course, there are some situations, like when we launched Segugio a long time ago – Segugio is our insurance comparison business, it’s a multiproduct comparison business but it’s mostly focused on insurance – we wanted to launch that as a brand-based business, so driven by television advertising, and we knew where to get the brand right for the business (it had to be something memorable and unique), and then we used a lot of research tools. But again, it’s mostly intuition and knowledge of the industry. It’s weird, but all the time we keep thinking and talking about how this is working, we could do this or that, whether we could create value by inventing or modifying a service…we do that all the time.

It’s mostly intuition and knowledge of the industry.

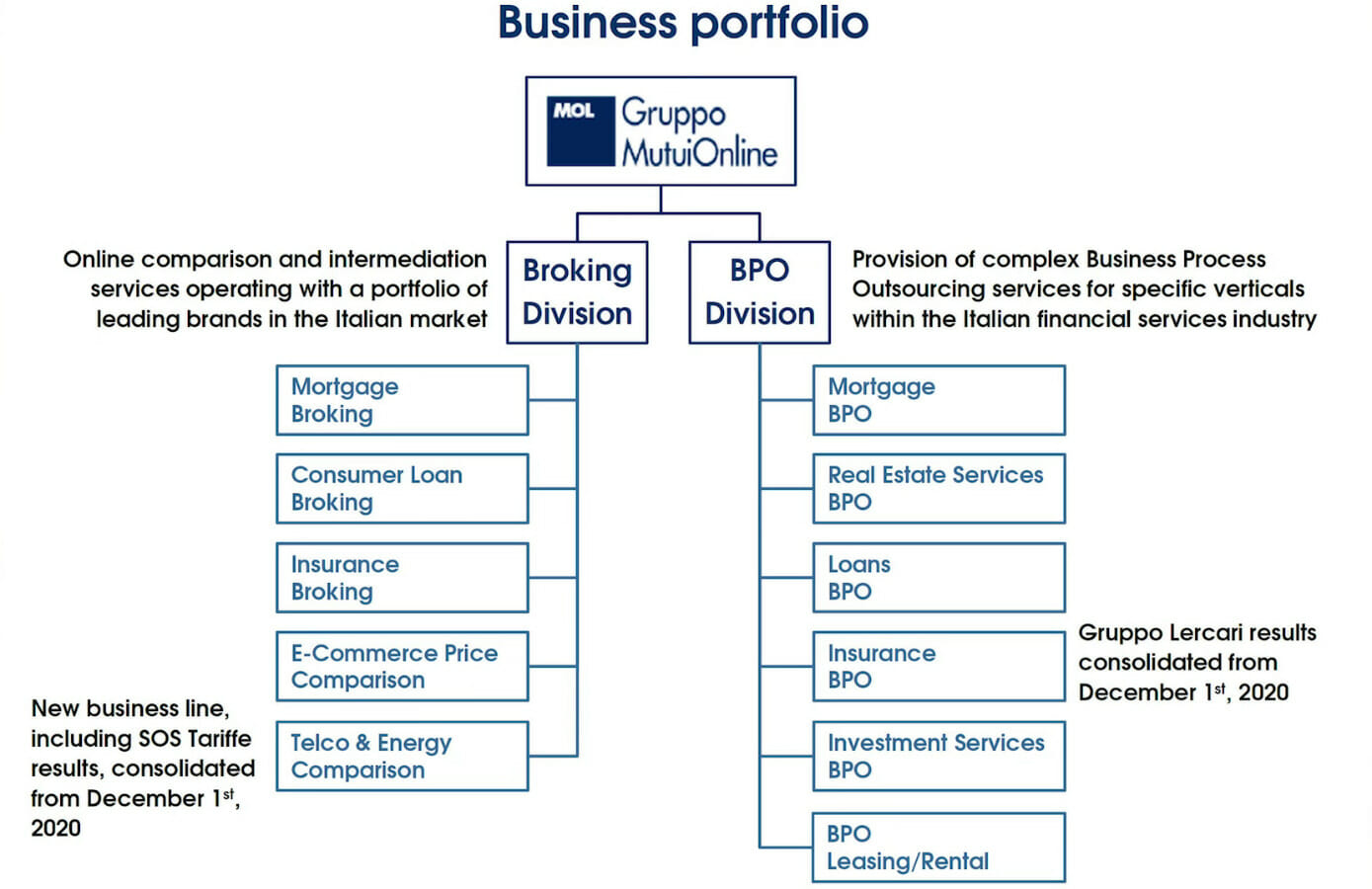

The divisions within Gruppo Mutui Online

[00:19:56] Tilman Versch: How autonomous are the businesses you build and acquire?

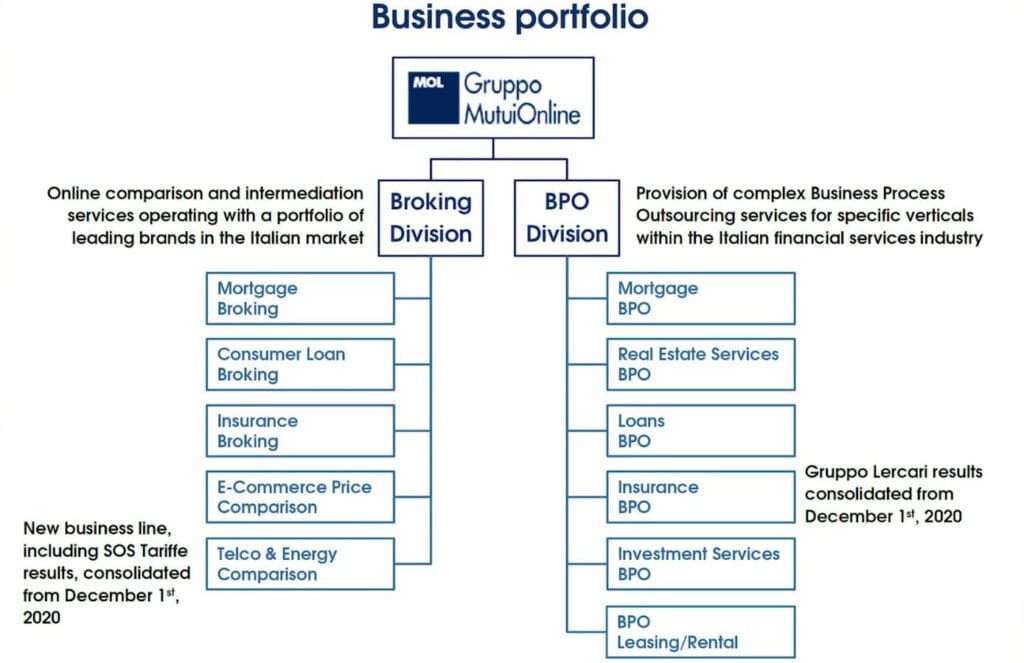

[00:20:04] Marco Pescarmona: That’s another interesting question and maybe it gives me the opportunity to clarify one point which is not always obvious about our business, which is the fact that within our group we really have two separate businesses: our broking division and our BPO division are structurally separate and autonomous businesses with very limited synergies (or dyssynergia for the matter). And then the question is – I would say your question is more of an organizational nature, and I would say within our broking division we tend to have tight coordination of all the businesses –

[00:20:49] Tilman Versch: I also have the chart prepared for this, so people can see these two business lines. I was coming to that chart later, but now we can go about it.

[00:20:58] Marco Pescarmona: Perfect, this is very useful. The answer in terms of the organization is different for the two divisions.

The broking division is a business that overall involves a relatively limited number of people because the operations are limited mainly, so its’ a few hundred people. The businesses of the broking division are run in a very coordinated way, so there is today – with the exception of price comparison which is still kept to a certain extent separate – but all the other businesses are run in a coordinated way by a General Manager. I used to do that activity myself, but now we have a General Manager who is leading the broking division. And again, that is done with a lot of coordination, in particular functional coordination, so activities like marketing, but also things that have to do with technology and so on are done in a coordinated way.

This is quite the opposite of what happens in the BPO division. Not fully the opposite, but I would say that in the BPO division basically, you tend to have more autonomous businesses. First of all, there is the issue of complexity, because there are between 500 and 2000 people working for the BPO division, so each of the businesses has a lot of people to manage. While for broking the clients are consumers in the end (I mean the end users because the guys that pay are the product providers, but you have to reach consumers and talk to consumers and talk), here in one case you talk to lenders, in the other case you talk to insurance companies, in other cases you talk to asset managers…so it’s quite different. These are niche businesses where you are the super specialist of the niche (that’s where the barriers to entry come from) and these are complex businesses, so you need a lot of domain competence. The most credible person within this business is the business leader who talks with competence to clients and has all the guts to deliver what the client needs in terms of service. So, this is the main organizational dimension.

These are niche businesses where you are the super specialist of the niche (that’s where the barriers to entry come from) and these are complex businesses, so you need a lot of domain competence.

We are still working – we used to have more coordination here, we are working towards more independence of the business leaders and a set of shared services, which is what gives you efficiency and scale. For instance, in the BPO part of the IP services, all the compliance (which is more and more important), administrative processes, and so on, all these things are in common, but the business part which is the key part is driven by a significantly more autonomous business leader.

The point for us is really – this is a point of also organizational design and tuning – it’s to find the right balance between entrepreneurship and the accountability of the individual managers and the need to have synergies and some share services which bring order and also efficiency. So that’s the situation and this is for us one of the key open points as we scale the business because the answer that works for a small company is no longer the answer that works for a larger company, as the one we are becoming.

The point for us is really to find the right balance between entrepreneurship and the accountability of the individual managers and the need to have synergies and some share services which bring order and also efficiency.

The founders

[00:25:47] Tilman Versch: Let me go back to the slide I showed before. How did the role of you and Alessandro change over time? I think at the beginning you were just running the business, but you have been building more…your role had to change a bit or not?

[00:26:07] Marco Pescarmona: We had to change a number of times, but so far it always worked well. At the very beginning, Alessandro was running the operations and I was doing more of the growth, planning the growth, and talking to investors. This was very clear especially in 2000 when basically my job became for six months to find the money to survive, to allow the company to survive, and Alessandro’s job was to deliver the performance that we needed to show that we deserve that money. For a number of years, I was planning the growth and he was running the operations. Then, when we started with the BPO division, we started changing this type of organization, and it naturally evolved as the two divisions really became two relevant entities. A split where I would run the broking division and Alessandro would run the BPO division, that’s been our main focus for a number of years. And also, I, for instance, was doing some other things, always more focused on talking to investors and so on, but in general the main responsibilities were these two.

As the group kept growing, we realized we could no longer run the different businesses first-hand. I mean, maybe it took us a while to realize that and we arrived a little bit late, but we decided to start hiring managers that could take over especially the day-to-day responsibilities of running the businesses. In my case, the solution was to focus more on a single person overseeing the bulk of the broking division, plus there is a person overseeing TrovaPrezzi, but it was more of an approach of finding someone who could replace me with a general management role. For Alessandro, it was more a matter of designing the organization and designing the roles for people that we have in the group so that they could have full accountability.

But in all cases, there is always a threshold when you realize that what you were doing before is no longer feasible, just because of the work hours, the demands, etc, and you realize that maybe someone that you take either from the inside or the outside could do it better than you and also you have a better life (but I think it’s more important in the interest of the company to have stronger management because also it allows you to keep finding opportunities for growth).

It’s more important in the interest of the company to have stronger management because also it allows you to keep finding opportunities for growth.

Time management

[00:29:45] Tilman Versch: So how much free time do you currently both keep?

[00:29:49] Marco Pescarmona: No, we don’t have free time…The problem is we still don’t have free time, because the company is like the air that is taking all the available space, so you add extra room and it expands.

Basically, my focus is, for instance, more on overseeing the administration area and I’m more involved maybe in M&A, I’m more involved in things that are a bit more of strategic nature, or that have to do with regulations and other things that are relevant for our businesses.

When we started, the first two years we were working 12 hours a day 365 days a year, so that meant fourteen hours even on Saturdays and Sundays. Then it became more normal, so we would work twelve hours a day and half a day on the weekends, and then in recent years it’s even a bit more normal, so we can count on the weekends off and we are no longer tied to the desk…but still, we are working much more than an employee. This is more than a full-time job and we try to reduce it, but it is still more than a full-time job. In the end, I think we are [00:31:44 inaudible].

Would he sell his share in the company?

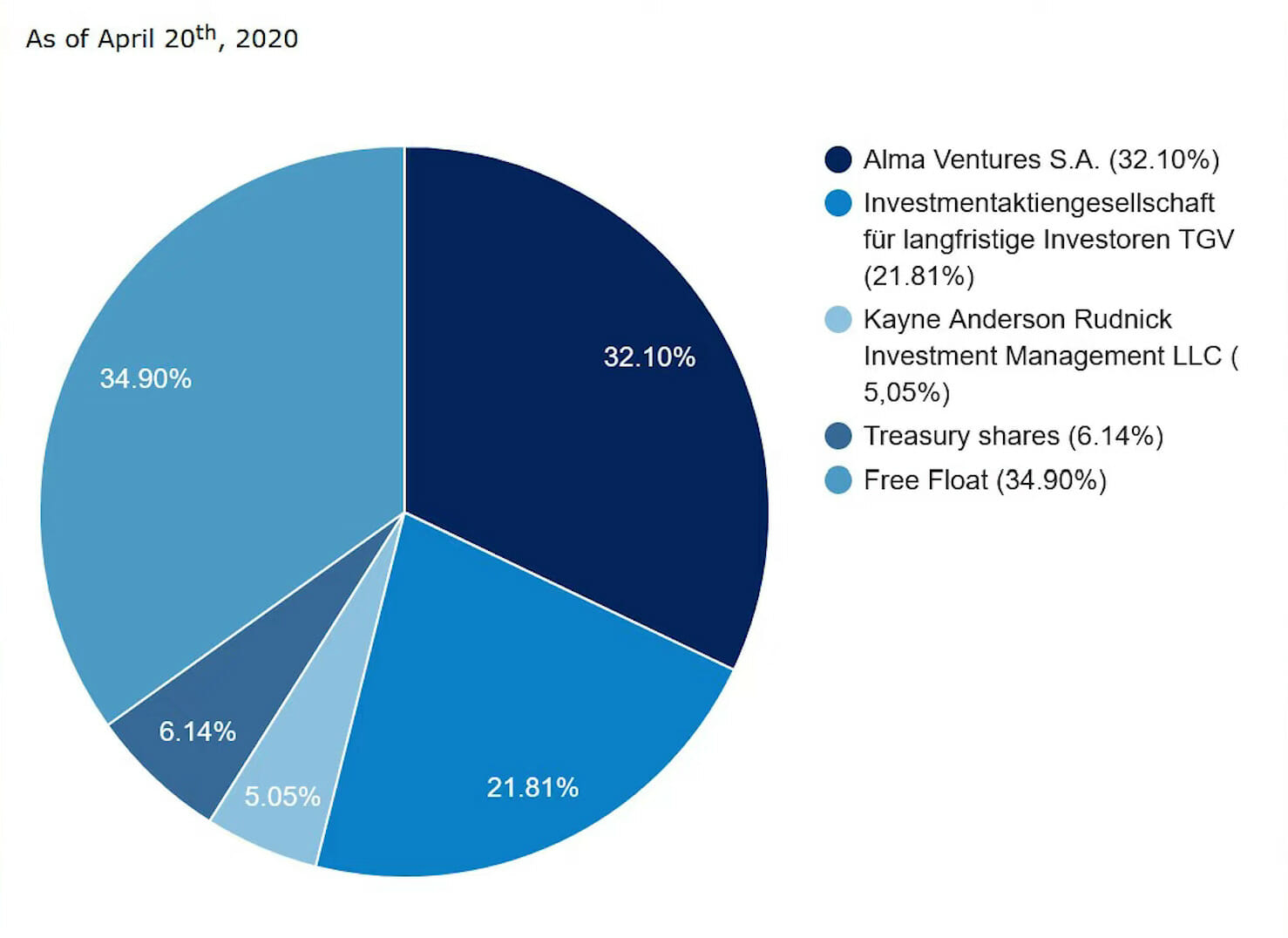

[00:31:46] Tilman Versch: That brings me to the question of ownership, I also prepared a chart on this. With Alessandro, you are currently holding 32% of the company. Let’s make an experiment: if I said that I would like to buy this 32% and I sent an email and asked if you were willing to talk about it, what should I write in there?

[00:32:16] Marco Pescarmona: To convince us –

[00:32:18] Tilman Versch: That you’re willing to sell or even talking about selling.

Going public with Gruppo Mutui Online

[00:33:03] Tilman Versch: Maybe let’s go back to 2007 and help me understand: why did you choose to go to the stock market? What was the reason?

[00:33:14] Marco Pescarmona: We had raised money from private equity, or better venture capital, at the beginning, and by the way, we had raised it at times that were not particularly favorable for us. Our commitment was to give them a liquidity event, and we realized that going public was a good liquidity event because it allowed them to realize a return on their investment and it would give us a lot of strategic freedom.

Our commitment was to give them a liquidity event, and we realized that going public was a good liquidity event because it allowed them to realize a return on their investment and it would give us a lot of strategic freedom.

I mean, I’m positive about the experience that we had, but it is more about the setup that we were concerned. What we suffered was the fact that there was a different type of horizon for a financial investor of that type and our horizon. So, we thought we had a lot of opportunities that were sometimes for the long term and we were not interested, for instance, in doing “cosmetic things” that make you look better today but don’t really bring benefits for the future and maybe bring complexity for the future. So basically, with the IPO I, and Alex never sold shares, especially since we didn’t in the IPO, we became basically the masters of our own destiny. Obviously, we knew we had to deliver, which I hope we did, but we knew that if we delivered, we would be allowed to run the company in the way that we thought was most appropriate.

Dividends or buybacks?

[00:35:06] Tilman Versch: Why did you choose the way to give back capital to investors by dividends and not buybacks? Because if you look at the long term, it would have been more value-creating to buy back shares.

[00:35:20] Marco Pescarmona: We did both, and we fully understand the point, and we are quite in favor of buybacks in general.

The problem is the regulations that allow us to do only a limited amount of buybacks over time – because, at least in our case, there are some regulations for which in order not to interfere with the stock price you are allowed to buy back I think no more than 20% of the daily volumes (which in the past was quite limited for a number of years). So we had a permanent buyback program almost since IPO that brought us to buy back 6-7% of the company. Also, we had some stock option plans for our employees, so part of the shares we bought back we consumed.

Today I think we have around 5% of the shares. Again, we are super in favor of buybacks. You could also do them with tender offers but it’s more complicated. You need a prospectus, it makes sense if you think there is maybe a gap between intrinsic value and the stock price and that is stable and you have the liquidity and so on to do that: that could generate value for all the shareholders and be a sensible capital allocation, but we never had enough time and we were never ready enough for something of that type.

In general, our view is: to the extent we are able to use the capital ourselves we use it. It’s not always easy, because as you were saying, you cannot really invest much within the business without doing M&A, and it depends on the opportunities you have. We are selective in terms of the quality of what we buy and the price we are willing to pay, and that again creates limitations. By the way, we are not looking to build empires; we would rather have a smaller company that is working pretty well than keep buying things. Given the choice, if we are neutral, we don’t do things, we don’t do M&A. We do M&A only if we really think it creates value, it makes our life more difficult, more complex…if it’s a good capital allocation we do it, but if we don’t know what to do with the money and we think there is a stable situation, we would return it as dividends or buybacks.

We do M&A only if we really think it creates value, it makes our life more difficult, more complex…if it’s a good capital allocation we do it, but if we don’t know what to do with the money and we think there is a stable situation, we would return it as dividends or buybacks.

Debt at Gruppo Mutui Online

[00:38:36] Tilman Versch: How much cash do you want to keep at hand? What do you think about that?

[00:38:44] Marco Pescarmona: We are not particularly allergic to that, but at the same time, having lived in risky times, at least for our company, we want to always have a certain level of safety. Our businesses are all quite cash-generative, so even if we take debt it tends to repay itself quite rapidly. I would say we would not be afraid to take debt to do value-creating M&A if we found something that really made sense; obviously, we would take a bit more risk or a bit more leverage if we had really compelling opportunities.

The other point about debt is that what we had found to be an effective combination to have both cash on hand and some leverage, because when you do M&A, at least this is our experience in Italy sometimes over turbulent times if you have money in the bank and you do an acquisition and you can say you use available cash – and it’s the bank account and you can show it – you are much more credible and it’s your own decision. When you need bank financing for a specific transaction, then the bank starts asking for the business plan, the combined business plan, and what you think of the market…you waste a lot of time explaining things to people that don’t really know what you are doing (but it’s impossible to know what you are doing). It becomes a lot of bureaucracy. So, our approach has always been: we buy things with the cash that we have, and then later we raise the financing or recharge the batteries, and so on.

So, the current configuration is good, maybe we have a bit too much cash, but we have cash and we have debt, and it gives this type of flexibility. If we were in very well-running markets, if we knew that bank financing is always available, then probably we would offset the two, so that’s our view on it.

Expansion strategies

[00:41:22] Tilman Versch: We’ve already talked a bit about M&A and heard between the lines something like price discipline and not paying too much. What are the multiples you feel fine with buying other companies?

[00:41:39] Marco Pescarmona: Anything above a single digit is already a bit of a stretch for us – it really depends on the businesses actually, of course. A fast-growing business or a business with synergies would deserve a higher multiple. So, we really look at the different situations. I would say for most of our acquisitions over the years we were able to apply a multiple of no more than say 9 (between 7 and 9). Obviously, that’s ideal and it depends on the business. Sometimes we did things at more expensive prices, either because there was growth there or because we knew there were hard synergies, but those were more the exceptions.

In general, we don’t pay big prices because of generic strategic value, we pay prices for specific things and also, we consider what the alternatives are if we could build something or do something different. So that’s the way we look at it. But we don’t look too much – of course, we have to take into account what the markets are for the assets, but if the market is paying crazy prices for something, the most likely thing that we will do is not buy the asset and not match the market price.

Synergies

[00:43:34] Tilman Versch: You mentioned synergies: have you really found them in the acquisitions you did? Because often synergies, if you look deeper, it’s just advertisement? The buy was good?

[00:43:48] Marco Pescarmona: No, no, no, that’s true, that’s true…I think we never bought much based on the synergies. We acquired a company that was doing real estate appraisals while we had an identical company doing the same and the synergies…we put together the IT systems, and in fact, as you correctly say, instead of putting them together in one year we are still working on it, so it takes a bit longer; eventually we will have the synergies but it took a bit longer.

We see sometimes commercial synergies which we never price in, which are normally the fact that we have maybe a higher level or better relationships that help to sell the BPO services of the companies that we acquire. Well, one case where we had fast synergies was with a recent acquisition of a utility comparison business. They’re basically the way you are remunerated is with volume incentives, and our business was significantly smaller than the acquired business, and basically, our volumes were switched from a low pricing commission bracket to the top bracket because it became the incremental bracket of the agreement of the acquired company. So that was quite immediate, instead of getting 90 euros per contract we were getting 140 euros per contract on our existing volumes.

So, sometimes they are tangible, they are there, and they are predictable; in many cases, as in the IT example, it still takes a lot of work to extract those synergies.

Sometimes they are tangible, they are there, and they are predictable; in many cases, as in the IT example, it still takes a lot of work to extract those synergies.

Gruppo Mutui Online’s clients

[00:45:52] Tilman Versch: Let’s go back to this overview of what I showed you of the different divisions. My question revolves a bit about the customer and the surplus you give to the customer. But as these are different businesses, maybe let’s go first about what is the customer. What are your customers?

[00:46:18] Marco Pescarmona: Ok, let’s look at the broking division. Here we really have two different actors. We have the product providers, that are our clients or even customers: they are the people that pay us for what we do, and basically, they pay us normally for helping them to sell their products to consumers (so it could be a bank that provides mortgages or it could be an insurance company), they pay us commissions for introducing business to them or even in some cases closing business on their behalf. In this type of business, in particular, this is very interesting because on one side you have these clients that pay you for what you do, on the other you have the consumers, who are the ones that really bring you the business. So, the way it works is that you have to provide services and benefits to consumers, so that they come to you, use your service, and as a by-product of your service you provide the introductions to your clients who will pay you commissions (because these are again intermediary marketplace services).

The way it works is that you have to provide services and benefits to consumers, so that they come to you, use your service, and as a by-product of your service you provide the introductions to your clients who will pay you commissions

So, in this type of business, you have to make two parties happy. You have to make, first of all, and this is what our focus is, the consumer happy because we always try to build lasting businesses which are based on the idea that the consumer comes first, so we try to provide significant value to the consumer so that they are happy of our service and they come back. In fact, this is for instance embodied in the fact that we always try to offer – you know, we compare products or services – we always try to do that in the most transparent and impartial way and we always try to offer the best product, to offer the cheapest (or maybe it’s other features than price) to the consumer for its own needs rather than what pays us the highest commissions (because commissions are not always aligned). We sacrifice something for the short term because we know that in the long term this will pay, it’s also our ethics. This is the “consumer first” principle here, that’s how we deliver value. Basically, we are really the best way for people to make both the right choice and the cheapest choice for a lot of household or financial needs.

This is the “consumer first” principle here, that’s how we deliver value. Basically, we are really the best way for people to make both the right choice and the cheapest choice for a lot of household or financial needs.

On the other end we have to deliver value as well to our partners because they want to acquire business profitably, they compare us with other channels, and basically, the idea is we behave fairly, correctly towards them, we try to be their most efficient customer acquisition channel and that’s taking into consideration both the price they pay us but also the risk we deliver to them. For instance, one thing that we do (also it’s difficult in our business but people try to do that) is we try not to interfere in the approval decisions or the risk decisions of our partners.

So, that means that normally the risk of the clients that we deliver to our partners is better than the risk they get from other channels, so they get value not only because we are a variable cost, reasonable costs in terms of commissions, but also because they get better clients, and that’s because we don’t interfere with their decisions processes, we don’t try to find tricks that make things happen. That’s basically the formula, and thanks to the fact that we are the most efficient channel we try to get the best products in the market and get competition, so it’s also a virtuous circle. Our channels for a number of businesses are really the most efficient way for demand and supply to meet in the Italian market, that’s what we are trying to achieve more and more as we keep developing the businesses.

Our channels for a number of businesses are really the most efficient way for demand and supply to meet in the Italian market.

In the BPO division, the clients are institutions, mostly financial institutions but they could also be other actors like sometimes it’s for instance owners of [00:51:55 inaudible] vehicles for the leasing rental BPO or sometimes public administrations (but that’s quite minor). But in the end here it’s simply “client first”, and what we do within our BPO…the idea is we run very specialized processes better in terms of quality, cheaper, and basically, we share these advantages with our clients. That means our clients if they did things in-house (which is normally the main alternative), would have lower quality maybe, would have certainly much higher costs, the costs would be fixed, so basically, there is a value gap between what we can deliver if we operate at cost and what it would cost them to do the things in-house and then basically this value is split between us and our clients. Depending on the level of competition, the alternatives, and so on, the value is split half and a half or more towards one side or the other.

Our clients, if they did things in-house (which is normally the main alternative), would have lower quality maybe, would have certainly much higher costs, the costs would be fixed.

In the end, we know we have to create tangible value for our clients, and this comes from the fact that we are specialized, that we have our own systems that are always proprietary systems, that we have a lot of competence, that we have the scale, that we have the diversification so we work with many clients in the same vertical so we can manage capacity better. So, we have a number of intrinsic factors that create efficiency and quality as well as give us an advantage, and thanks to that we can serve our clients better. We see our clients as partners and we don’t charge for every exception or change they ask for or anything: we tend to have simple and transparent pricing, and long-term relationships, and we try to have a fair split of the value that we generate between us and our partner clients.

Maintaining high quality

[00:54:31] Tilman Versch: How do you make sure that in all these different processes the quality for the customers is good or even great?

[00:54:40] Marco Pescarmona: Well, again, it depends on the different businesses. In consumer businesses, you just ask the consumers, so you do net promoter scores, and you keep monitoring a lot of KPIs.

[00:54:55] Tilman Versch: What are your numbers there?

[00:54:57] Marco Pescarmona: No, there are no numbers to disclose here, but let’s say, net promoter score is 85-90% for mortgages, so basically, there are almost no people that have complaints. Within BPO, what we track are a lot of key performance indicators. Sometimes the clients are very much on top of it, so if there is a problem, they will report it immediately or complain, sometimes they even exaggerate, but quite often they could be a bit detached, and then maybe they realize there is an issue all of a sudden after two years and if that happens you have a problem and it’s very difficult to recover from that.

We always try to run the business with KPIs that we monitor, even in a detailed level for the main processes and so on, and if there are issues with any of those KPIs we intervene even if the client is not really complaining. Obviously, it’s always a matter of balancing capacity and a number of needs with the delivery, but we always monitor the businesses in a numerical way, it’s quite detailed, so we make sure – or ASLs, sometimes there are ASLs, sometimes there are just internal KPIs – we always make sure that internally things are monitored and run in a way that is good for the clients.

Thought experiment: reducing to 3 promising businesses

[00:56:52] Tilman Versch: Let’s make another experiment. Let’s think that an unfair god comes to you and says you can only keep three of these businesses and you have to pick the ones that you think will perform best over the next ten years. Which one would you pick? You can only keep three.

[00:57:15] Marco Pescarmona: Ok [00:57:16 inaudible]. Certainly, I would keep mortgage broking

because it’s always been strong and there are a lot of barriers and we think it has a lot of upsides still.

I would…now it gets difficult. Even if it’s a small business, I would possibly keep consumer loan broking, because it has a lot of growth potential. Maybe we didn’t run it perfectly well in the past and this is running at a national market share of 1% while in all other countries it’s 10%, I would want to gamble a bit on this.

And then, within BPO, where I am a bit less expert, my gamble would be maybe on one of the new things: one that is quite interesting and that is also a challenge for us is insurance BPO, maybe I’ll try to keep that even if it is again a gamble, because this is a totally unstructured industry, and if there is a consolidation and it goes from a situation where insurance companies work with individual professionals to a situation where they work with companies, we stand to win big time in this business. And again, I’ve made a choice of one safe bet, which is mortgage broking, and two risky ones…just to hedge.

Risk and reward

[00:59:13] Tilman Versch: Let’s go a bit deeper into the risky ones. What is attractive for you in them that you say in ten years, or let’s say five years because maybe ten years is a bit too much, what good could happen in these businesses if they perform well?

[00:59:28] Marco Pescarmona: Well, it could happen that they grow by a multiple, so they become…for instance, consumer loan broking becomes five times what it is now, or we could build, as an insurance BPO, such a strong and leading position that we would have a very strong player for a very long period of time. Basically, these are the situations where we see more change happen or more potential change happen, and so they are interesting bets. But the truth is the question you asked is an unfair question…

[01:00:35] Tilman Versch: It’s an unfair god, sorry!

[01:00:38] Marco Pescarmona: Because the reality is all our businesses have – the broking division has an underlying penetration trend that is across the board and that is visible for all the products, and maybe with a random walk but they will all have significant upsides, and for the BPO division the outsourcing trend is also a clear trend that gives us across the board a significant upside. So, it’s really picking some random bets.

Challenges in broking

[01:01:20] Tilman Versch: What are the problems that you experience across the businesses that still are what you would call hurdles you have to cross or the challenges you have in these businesses? You don’t have to say it for every business, you can pick one or two or three…

[01:01:36] Marco Pescarmona: I would say, for all the broking businesses, the challenge is that in theory, you would expect penetration of the internet channel to increase over time, the reality is that you have to make things happen for this to happen. You don’t see just an increase in business volumes by itself: it normally happens because you keep innovating, you keep doing things, and you keep spending more on marketing. So, translating on the broking side what everybody thinks (and we also think) is a clear potential into actual growth is an execution challenge, you have to continue delivering improvements on a lot of things because there is an expectation there will be growth, but the growth doesn’t fully come by itself, you also have to do things, that’s one side.

You don’t see just an increase in business volumes by itself: it normally happens because you keep innovating, you keep doing things.

On the BPO side, I think the issue is managing the complexity, and the complexity is coming in many cases from regulatory evolution, it comes from the authorities, it comes from GDPR, it comes from a lot of IT compliance requirements. Being agile, being entrepreneurial, and at the same time managing in a correct way this complexity (we don’t want to take risks but we don’t want to become bureaucracy), so managing this balance in a way that is effective so that we are still faster and more agile than all the potential competition but at the same time without taking an unnecessary risk: that’s a challenge for our BPO division.

On the BPO side, I think the issue is managing the complexity.

Effects of regulation

[01:03:58] Tilman Versch: Is regulation making you stronger in your business possession or how do you see it?

[01:04:06] Marco Pescarmona: I think it is. I think it is because it’s another thing that is deepening [01:04:13 inaudible]….entering in some of these businesses is now very difficult, also some of the companies we acquired were set up by people that were experts at something and had few initial contacts, and without any particular formal structure but just by being better at those specific fields they were able to acquire clients; today they would no longer be able to start similar businesses, they would need to get a DPO, to get this or that, have ten procedures in place before they even open the doors. So, I think regulations in all of our businesses are making a market entry for smaller players, unstructured players, and even start-ups, quite difficult.

At the same time, it’s a drive on everybody, so it is reducing the efficiency of what we are doing sometimes. But in the longer term, I think it’s going to be positive for the business. For the entire system, I don’t know, because too much regulation tends to reduce innovation, but for us, I think in the end it will be ok.

Future plans

[01:05:44] Tilman Versch: Another experiment. Let’s say we are meeting in five years again, I show this chart again. What might have happened? Could there be a third angle or a fourth angle, like Gruppo Mutui Online France for instance, or could there be more verticals here? What do you think?

[01:06:07] Marco Pescarmona: What is most likely is that there could be some more verticals under BPO because there are things that fit and that we could develop internally or acquire. But I wouldn’t rule out new verticals in BPO. Within broking, it is more difficult to find new verticals.

In terms of Mutui online France, I think that’s quite unlikely, because our strategy is – I mean, we think we have a lot of growth opportunities. Even if we don’t expand too much, we have a lot of growth opportunities and our capital is execution capital in the end, what drives the growth, and this execution capital which we try to expand by reinforcing the management, the IT staff, and so on is better deployed in Italy where we have experience, where we have contacts, where we know how to do things, where we know the regulations. So, we think that as long as we have opportunities for growth in Italy, we think we have plenty, and we’d rather stay at home.

As long as we have opportunities for growth in Italy, we think we have plenty, we’d rather stay at home.

Of course, if someone comes and wants to sell us for cheap a nice business in France that maybe we know even how to restructure and it is sizeable enough maybe we would consider it, but it would be very opportunistic, and we consider it unlikely. So, if someone wants to make us a big gift in Germany, we will take the gift, but we are not even looking for that.

[01:07:58] Tilman Versch: I see. Also thinking about the experiment of five years: could there be a business that is not on the list anymore that you might have closed because there was too much competition?

[01:08:13] Marco Pescarmona: No, no. Never say never, but I don’t think there is any risk of this type in terms of closing a business. What I couldn’t rule out, but this is what we always say also with investors, is that maybe – these two divisions are not designed to fit together. There is a capital allocation synergy, yes, but the two businesses are independent. Maybe there are regulatory evolutions or other changes that will increase our propensity to split the two things off.

So, we could have either split the group into two separate businesses or one could have been sold for a ton of money to someone who was really keen to take it. So, a possibility is to have only one of the two divisions left, I don’t know which one because we like both, but that’s not because it could have run out of business but because it could have been separated or maybe sold.

Marco Pescarmona on Dealing with competition

[01:09:33] Tilman Versch: So, competition can’t really hurt you badly or is there a chance that competition might be a problem for one of the verticals?

[01:09:43] Marco Pescarmona: I think we’ve had very intense competition for a very long time, so it can become sometimes irrational but there is no competition that we think could kill our businesses. And again, these are businesses with as you say modes, the modes protect us and also the other incumbents in these businesses, this keeps competition…normally it remains intense, but it doesn’t become crazy.

The risks are more technological maybe, so for instance take the BPO division as an example: if you had an intelligent system, so artificial intelligence, general artificial intelligence, of a quality that could do the tasks of specialized employees (the guys that work for us and maybe underwrite mortgage or process complex activities), if you could have that type of general artificial intelligence, then these businesses could change dramatically. It could be either that we adopt all of that and we end up running the same business with very few people and more with technology guys and design guys and so on, or that this technology makes our type of business obsolete (say insurance broking, which is mostly motor insurance: if because of technology cars no longer have accidents, there is no reason to have insurance or the premiums will be so tiny that the business will evaporate). These are risks that we don’t see as immediate risks, but in theory, are longer-term risks. Competition is, we think, manageable, it’s part of the way it should be, and it will not kill us.

Competition is, we think, manageable, it’s part of the way it should be, it will not kill us.

Dealing with big players like Google

[01:12:21] Tilman Versch: So, you also see the risk of Google or Amazon as manageable or do you have different concerns?

[01:12:28] Marco Pescarmona: Yes, we see that as manageable. We have had the full impact of Google in e-commerce price comparison, Google was even fined for an abuse of dominant position for its activities in e-commerce price comparison because the Commission decided it favored Google Shopping in an unfair way; of course, it created a lot of damage, it reduced the potential of our business, but still, the business is alive and profitable. So, obviously, it reduced the potential, but it didn’t kill the business. In the other verticals, I think it will be more difficult for Google in particular, or Amazon, to enter as a direct competitor for a number of structural reasons, so we think those risks are also manageable.

Also, the risk of the entry of those players normally comes from the fact there is such a dominant position that they might try to leverage, so if that is legal then there is more risk, if that is made more difficult by new legislation that Europe is considering then I think even that is under control. So, we are not afraid of fair competition in general, we think we can beat or defend ourselves pretty well.

Characteristics of the Italian market

[01:14:21] Tilman Versch: You already made a point that you are a focused Italian company. You will have some investors coming back to Italy, traveling again soon; if they meet you in meetings or if they meet you over Zoom, what are the stories you have to tell them to understand Italy better and what are the unique points of the Italian market compared to the markets they come from?

[01:14:46] Marco Pescarmona: Well, the truth is that there are many fewer differences. If you look at a number of figures, you will see that the Italian market is maybe behind in many of the services we provide in terms of penetration, but then if you look at the population of the country, the education level, etc, the differences are not too big, so it’s mostly a matter of adoption of our services.

I think it’s like with supermarkets: when I was a kid, we would go shopping to a small store, the milk store in front of my house, we would buy a few things and there were just two guys running the store, and that was the normal way of shopping, there were no or very few supermarkets, and I would travel with my parents to France and we would stop and visit the hypermarkets because they were huge and completely different and they were really interesting for us to see. So, back at the time, Italy had local stores and France had supermarkets already there like the US; today the two countries are exactly the same from the point of view of retail distribution. I think this is the same type of situation. We will see a convergence towards a very similar situation for a number of reasons that depend on the individual markets.

Italy is behind in the curve, but we will get to a very similar point, because when they tell you that Italians are not so interested in saving money that’s not true: it’s that they don’t know they can do it in a particular way, they are not used to doing transactions with a computer, but as soon as they learn, they’re fine. So, the differences are in terms of the degree of maturity, but there are no fundamental differences, we would say.

Also, as you look and talk to people in other markets, you realize there are many more commonalities between European markets than you would think like regulations are increasingly becoming convergent, a lot of things are becoming convergent. So, my point is there is nothing particularly special about Italy that you need to understand to interpret what could happen; it’s a European country with people that are very similar to other Europeans.

There is nothing particularly special about Italy that you need to understand to interpret what could happen; it’s a European country with people that are very similar to the other Europeans.

The impact of Covid

[01:18:18] Tilman Versch: You mentioned that Italy is some years behind. Now we had Covid, with some tragedies in Europe, and in Italy as well. How did this change your business trajectory? Did you jump up ten years in the future or where did this take?

[01:18:38] Marco Pescarmona: We saw a good acceleration, we hope it’s not a one-off effect, certainly there is a lasting component. It was like a force training session for a population that was not fully trained for the use of digital devices, channels of communication, and so on. So, I think this was – let’s put aside the sad aspects of the pandemic and the losses and so on – this was quite positive for the digital evolution of the country, and I think for a country that was a bit behind as Italy the beneficial effect was probably bigger than what you had to say in Germany or other places where some things are already commonplace.

[01:18:32] Tilman Versch: You mentioned one-off effects. Where do you think it could be more of a one-off effect and where do you think this might be a structural change?

[01:18:44] Marco Pescarmona: I think it’s more of a structural change and it’s basically forced training. It was forced training for the Italian population. The fact that we were behind probably means that the positive impacts of this forced training were more significant than the impact in other countries.

I give you an example for instance: now to get the vaccines in Italy you basically need to have a sort of a government ID, a digital ID, which is a secure ID that you need to log on to do the booking, and this is a standard form of digital ID that you can use to access all the public services (be it the tax authorities, or the health authorities, whatever), and the adoption of these digital IDs was quite limited before. Now, given that you need to have it for the vaccines, everybody has it and this allows you, once you have learned to use it (and it’s quite simple) to get certificates, to get this and that in a simple way; that was already there, but people just didn’t use it or realized it. So, once you have learned to do these things, you understand that they are easier in a new way. I’m very positive about what happened from this point of view.

Pressure after the good performance in 2020?

[01:21:31] Tilman Versch: That’s interesting to hear. This year you had a special good year because you also had these tax benefits, maybe also the effects of Covid. Do you feel a certain pressure over the next years to be as good as this or what do you think about it?

[01:21:47] Marco Pescarmona: We never felt pressure because of our results, we never tried to smooth the results. We tried to do as best as we can; we know there could be ups and downs. It would be of course challenging to deliver a good performance after the extraordinary one of 2020, but we just do our best and the results will follow and they depend on a number of factors. But no, we never felt pressured because either of the stock price or of the results, especially when they are dependent on external factors.

It would be of course challenging to deliver a good performance after the extraordinary one of 2020, but we just do our best and the results will follow.

The outlook with Marco Pescarmona

[01:22:44] Tilman Versch: To come to end, I want to do an outlook: how do you feel about Gruppo Mutui Online in five or ten years? Do you have some kind of vision where you say “we will be there in 2030” or are you going very opportunistic and down to the ground and hard-working about it?

[01:23:04] Marco Pescarmona: Well, the thing is we have an implicit vision, but we don’t articulate it too much. I would say we’ll keep growing what we have, we’ll be opportunistic, and we’ll try to exploit the options that present themselves. But this is not done in a blind way; this is done by trying to understand how the industry will evolve, how the markets will evolve, what happens in the rest of the world, and charting an implicit strategy to exploit or to prepare ourselves to exploit the opportunities. But we don’t articulate it in an explicit way.

We’ll keep growing what we have, we’ll be opportunistic, and we’ll try to exploit the options that present themselves.

The most likely outlook is that you will find us maybe with a slightly broader portfolio of activities, with stronger positions, bigger and with stronger management, and maybe we will have addressed some of the challenges that we were discussing before and some of the other challenges (such as artificial intelligence) will have translated into opportunities.

Maintaining a feeling of familiarity in a growing company

[01:24:40] Tilman Versch: For the end, I want to give you the chance to tell something we haven’t discussed. Is there anything interesting about Gruppo Mutui Online you want to add?

[01:24:51] Marco Pescarmona: No, maybe I will just say that Alessandro and I are still sitting in the same office…we’ve become a medium-size company, but it still feels like not a start-up but just a bit more than a start-up!

[01:25:15] Tilman Versch: Are there any start-up traditions you still have in the company? Like, “Monday singing together” or something like this?

[01:25:24] Marco Pescarmona: No no no, we don’t do any…we are quite normal in a way, we don’t do anything that stands out. We are just businesspeople, we try to build something that makes sense for all the actors (for consumers first), and this drives value, and we want to make our shareholders happy. All that we do are simple things in the end.

Goodbye

[01:25:53] Tilman Versch: Then thank you very much for these insights and that addition of many simple things you gave me today. Thank you very much for your time.

[01:26:03] Marco Pescarmona: Thank you Tilman.

[01:26:04] Tilman Versch: Bye-bye to the viewers!

[01:26:05] Marco Pescarmona: Bye bye!

Disclaimer

It’s great to have you on as the CEO and also the owner of Gruppo Mutui Online, a very interesting business from Italy, which I think is one of the most interesting businesses from Italy. I find it so interesting that I also invested there, so full disclaimer: always do your own work, my interview is done partly as a shareholder, I also have some pretty good questions but I’m also a shareholder in Gruppo Mutui Online, so please do your own work.