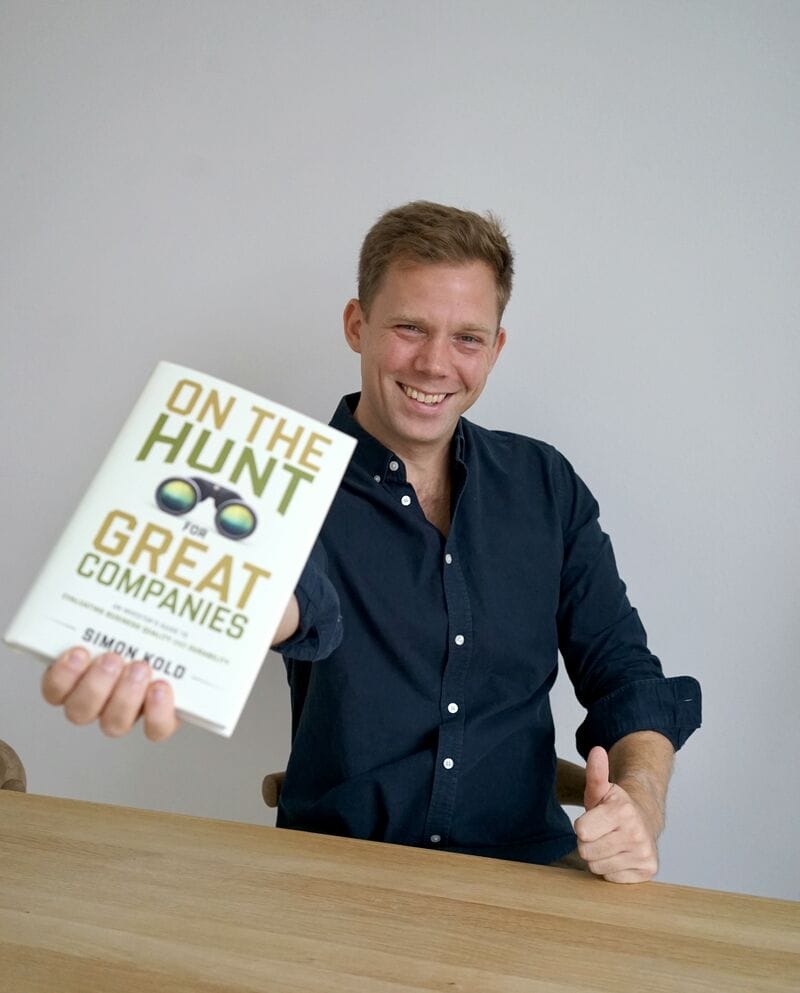

Simon Kold published the very entertaining and insightful investing book “On the Hunt for Great Companies: An Investor’s Guide to Evaluating Business Quality and Durability“. Here, you can learn more about the book and the value it will add to you.

Follow us

Easily discover all topics discussed by clicking on the table of contents:

- Highlights of "On the Hunt for Great Companies"

- Introducing Simon Kold

- The ideal reader for “On the Hunt for Great Companies”

- Implementing the ideas of the book

- Types of investing books

- Offending certain types of investors with "On the Hunt for Great Companies"

- Surprises for the readers

- Company examples in "On the Hunt for Great Companies": Apple, Berkshire and more...

- Identifying greatness in a company with "On the Hunt for Great Companies"

- Thought patterns in evaluation that can make investment decisions go wrong

- Popular myths

- The role of passion in "On the Hunt for Great Companies"

- Things to look for in a company

- How did writing "On the Hunt for Great Companies" change Simon Kold?

- On writing "On the Hunt for Great Companies"

- Closing thoughts & recommendation

- Goodbye

Highlights of “On the Hunt for Great Companies”

[00:00:00] Simon Kold: There’s a lot of humour in this “On the Hunt for Great Companies”. I don’t know if I mentioned that but it sort of happened accidentally. First, I wrote the first draft of the book. It was how I intended. And then people were saying like, I don’t recognise your personality. I started adding humour and humour.

So the book is quite different from stylistically, I think, at least from most investment books. And I was quite surprised by the impact that had on people’s ability to also read the book. I had an idea for– I thought there was some missing practical book like, yeah, there’s a lot of good books on mental models on how to evaluate various aspects of quality.

Like quality investing, even though I wouldn’t say “On the Hunt for Great Companies” is about quality investing, it’s about evaluating quality, but I think a lot of them lack the kind of practicality. What are the empirical determinants that you want to see? And I wanted to write a book about that, but then sort of accidentally it also became a book that is stylistically very different.

This book has a more narrow focus. It focuses only on evaluating quality, and it doesn’t mean that it’s a book about quality investing. It’s just a book about evaluating quality and quality as an input through determining the value of something, and then because it’s more narrow. It’s also a little bit more focused and maybe a little bit more advanced.

Introducing Simon Kold

[00:01:14] Tilman Versch: Dear viewers of Good Investing Talks, it’s great to have you back and it’s great to welcome Simon Kold. He’s a book author and is about to release a very interesting book. It’s called On the Hunt for Great Companies: An Investor’s Guide to Evaluating Business Quality and Durability. So Simon, great to have you here.

[00:01:32] Simon Kold: Great to be here, Tilman. Thank you.

[00:01:37] Tilman Versch: Great to have you. And today we want to talk about your book, but before we dive into the book, maybe let’s add a bit of background around you. So who are you and why you’re qualified to teach someone with a book on the hunt for great companies?

[00:01:54] Simon Kold: Yeah, so I’m Danish. I worked for 10 years at Novo Holdings, the investment arm of the Nordic Foundation, which is the world’s largest private charitable fund but compared to US foundations and so on, it’s much more direct investments and much more private markets mindset.

I have a little bit of an unconventional background in investing in the sense that I also have a bachelor’s degree in theology and I used to do stand-up comedy here in the Copenhagen comedy scene 15, 16 years ago that I sort of accidentally also bring to the book. I thought there was a missing practical book like “On the Hunt for Great Companies”.

There are a lot of good books on mental models on how to evaluate various aspects of quality and quality investing. Even though I wouldn’t say my book is about quality investing, but it’s about evaluating quality. But I think a lot of them lack the kind of practicality.

I thought there was a missing practical book. There are a lot of good books on mental models on how to evaluate various aspects of quality and about quality investing. Even though I wouldn’t say my book is about quality investing, but it’s about evaluating quality. But I think a lot of them lack the kind of practicality.

What are the empirical determinants that you want to see? And I wanted to write a book about that, but then sort of accidentally it also became a book that is stylistically very different. But that was not the plan in the beginning. The plan was to write this dry practical investment book, almost like a textbook on how to evaluate business quality in investment analysis.

[00:03:14] Tilman Versch: So your qualification from Novo Holdings is that you did a lot of investments into great companies there with their direct investment team?

[00:03:25] Simon Kold: Exactly. It’s based on my practical experience from 10 years of investing. But it’s also just based, I would say, on synthesis of everything I have read. Like all the books on specific aspects, all the academic research and so on that I have read in stuff that I have tried to integrate in my work, I have tried to synthesise in “On the Hunt for Great Companies”.

So I wouldn’t say that every single word is derived from a particular transaction or something that I was directly involved in, it’s just based on the synthesis of information and my practical experience.

The ideal reader for “On the Hunt for Great Companies”

[00:04:05] Tilman Versch: That’s a great background for such a book and who would be the ideal reader for your book?

[00:04:12] Simon Kold: So I think it has multiple kinds of readers, but I think for sure if you’re young, you’re into your investment career, maybe you are one to five to 10 years into your investment career, there will be a lot of stuff in this book that is sort of applicable in your day-to-day analysis.

So I think that you will see the book having a sweet spot there, but then, because of the stylistic aspects that are mentioned, I think the book will have a much broader reader base. I think it will be enjoyed by also very, very seasoned investors who I know liked it. I had 40 reviewers but I think also people who are beginners or amateur investors will like it. I have these boxes with analytical steps you can take.

And since they’re in this box, you can just skip them. So if you are like an amateur investor, you’re just interested in learning about it. You can just skip these boxes and then the book is also very accessible to you. So I think it will have multiple kinds of audiences.

Implementing the ideas of the book

[00:05:20] Tilman Versch: So maybe imagine a reader who bought the book before he started reading it, and after reading it, what kind of transformation does the book “On the Hunt for Great Comanpies” do with someone when they read and study the book closely?

[00:05:33] Simon Kold: So I think, what I saw, I had 40 different reviewers and most of them are quite experienced investors and what I saw the pattern that some of the chapters, people kind of they understood the concepts very well.

They know it already it’s kind of known things like networks. So staying power or something, but maybe they hadn’t thought really through how to test the durability and the intensity of a certain aspect. They each had blind spots where they took away something. I don’t think there was a single person who was like, I knew everything in this book. I don’t think there was that.

So and then because it’s sort of a unified framework for evaluating quality, it’s also very tangible, like you can just implement it if you want. I mean, I’m not encouraging people to systematically go through this as an analytical model because I think it might be a little bit too cumbersome for some people, but you can pinpoint down what’s the most important aspects of your particular investment case you’re working on and then use it basically as a guide to say, OK, so these are the hypothesis I want to test. What is the specific information I need to look for to test it?

So I think that’s what people will take away. Of course, the less experienced you less investment books, you have read, the more novel everything in the book will be. But I think even for someone who has read everything, I think there will be new things. In the appendix, there’s also this. It’s a different kind of checklist.

It’s kind of a list you can use to check your own investment hypothesis for sort of logical flaws. And I think that is probably the most original part of the book that at least I haven’t seen or heard anybody describe that before. And I think that is something that probably everybody can use.

[00:07:22] Tilman Versch: So everybody should check out the appendix.

[00:07:25] Simon Kold: They should check out the whole thing. They should check out the whole thing.

[00:07:30] Tilman Versch: But we are all a bit time-constrained and are there ways you would recommend to do if you want to read the poke with a limited time? You already mentioned these boxes.

[00:07:45] Simon Kold: Well, I mean. These boxes are sort of the, you could say the optional advanced version, so if that’s not for you, you just sort of a casual interest in investing, you just skip those and just read the book.

Then I think it’s a very enjoyable read but if what you want is more like looking for the specific tools to analyse certain things, I think the boxes are where you have like the value for you, so I think depends on the kind of who you are.

[00:08:15] Tilman Versch: So if you want to read the book within a limited time and quite efficiently, go for the boxes or skip the boxes.

[00:08:22] Simon Kold: That depends on who you are. It depends on who you are, and what you’re after. So I have some of my friends who are not investing, friends who read the book. They understood the books, but I asked them. So did you skip the boxes? And they were like, yeah, I skipped the boxes.

But then I have other people who are, like, really hardcore professional investors and they liked they like that part. I mean there’s a lot of humour in the book. I don’t know if I mentioned that but it sort of happened accidentally.

First, I wrote the first draft of the book. It was how I intended and then people were saying I don’t recognise your personality. I started adding humour and humour so the book is actually quite different from stylistically, I think, at least from most investment books. And I was quite surprised by the impact that had on people’s ability to also read the book.

So, people who are not investors, they can actually, I think because partly of the style they get engaged by the book, but they get kind of turned off by these boxes, I think, because of this kind of bizarre combination between a pretty advanced investment book and then kind of comedic tricks. It’s a kind of combination that doesn’t make sense, but anyway, now I did this.

Types of investing books

[00:09:35] Tilman Versch: So you already mentioned that humour is an ingredient to make the book different. What else makes it different to other investing books?

[00:09:45] Simon Kold: So, well, I think if you stripped out the humour, I think it’s still very different. You know, there’s a category of investing books that I would call toolbox books that are very practical, very like, not so much mental model very much like this is kind of how you do it. Like for example, Pat Dorsey’s book, is great, and I highly recommend it.

But I think this book is sort of a more narrow focus. It focuses only on evaluating quality and it doesn’t mean that it’s a book about quality investing. It’s just a book about evaluating quality and quality as an input to determining the value of something, and then because it’s more narrow.

You know, there’s a category of investing books that I would call toolbox books that are very practical, very like, not so much mental model very much like this is kind of how you do it. Like for example, Pat Dorsey’s book, is great, and I highly recommend it. But I think this book is sort of a more narrow focus. It focuses only on evaluating quality and it doesn’t mean that it’s a book about quality investing. It’s just a book about evaluating quality and quality as an input to determining the value of something, and then because it’s more narrow.

It’s also a little bit more focused and maybe a little bit more advanced. So I think that is where it stands out. I think that to my knowledge, that book doesn’t exist today. But then of course, then you add on that stylistic aspect, which makes it sort of almost freakish. I don’t know. it wasn’t my plan originally as I mentioned. I mean, if I had wanted to write the world’s first comedy book, investing book or something, I would have probably approached it totally differently. But anyway, now it’s this way and people seem to like it.

Offending certain types of investors with “On the Hunt for Great Companies”

[00:10:56] Tilman Versch: OK, then prepare for a lot of humour when reading the book. So imagine a group of investors and maybe let me ask the question based on this imagination, which investors might be slightly offended when reading the book “On the Hunt for Great Companies”?

[00:11:11] Simon Kold: Yeah. So since the book uses sort of satire a Lot and sort of these, you could call them exaggerated analogies. Like you take an argument and then you kind of take it to the extreme in two contrasts. And I use that a lot. So of course there are some people who get sort of satirised along. I think number one is probably the kind of very heuristic thinking.

The people who are very like binary like you have the very thing you have cyclical industries and non-cyclical industries and it’s kind of carved in stone. This is like God came down to Earth and he said it’s cyclical and non-cyclical that’s not a scale or people who think a lot in terms of like, just heuristics, like Roy or PE or ratios or and don’t think qualitatively about stuff and go to the next to the deeper level of the determinants behind.

What are the leading determinants of durable high return on invested capital instead of just what is the ratio I can pull up on Bloomberg, you know? And I kind of satirise them a little bit and then of course I also satirise people who just who just kind of lazy in terms of their analysis, who seek verification of their idea instead of seek falsification of the idea, right?

And there’s a lot of stuff they get kind of grouped in as I call them dowsers you know they look for water with a stick or divine us you know I have these illustrations and. So, of course, it’s an exaggeration. If people get offended by it, they should be like, hey, we are all guilty of doing that from time to time. But I think it’s just an effective way to get my point across.

[00:12:59] Tilman Versch: It will be interesting what feedback you will get on the book outside of the sample you already have.

[00:13:04] Simon Kold: For sure there will be some fundamentalists who will read the book very, very like the same way you have some people who read the book like a religious fundamentalist or something. But I mean, they’re welcome to criticise me. If you can’t take a little bit of humour, then maybe I don’t know.

Surprises for the readers

[00:13:23] Tilman Versch: What are free insights that I can get from the book that might surprise me as a reader?

[00:13:30] Simon Kold: It depends a little bit on you, Tilman because I kind of don’t know where your holes are in. So I think based on my experience from 40 reviewers, everybody had something different where they were like, hey, I hadn’t thought about this before, so it’s hard for me to pinpoint.

The concept of the book is not to present one original idea and just go through it the whole book, like for example I can checklist manifesto or something. It’s 17 different aspects of quality and how you empirically assessed them. So if there were maybe two or three of those 17 that you had maybe not thought so much about the determinants of them, that would be the two, three things that I think you would take away. But for someone else, it might be something else.

[00:14:15] Tilman Versch: So what is there any pattern you have seen of surprises?

[00:14:24] Simon Kold: Well, I think the chapter on staying power, there’s a chapter on staying power with the determinants of staying power. I think maybe you had, like, a little bit higher percentage of people who hadn’t thought about that.

There were also a lot of people who I think, hadn’t thought about some of the analytical methods to evaluate the reliability of people of have simulated following the company for a long time. I also, maybe there was a higher proportion of reviewers who hadn’t thought about that.

Company examples in “On the Hunt for Great Companies”: Apple, Berkshire and more…

[00:14:57] Tilman Versch: Now people should have a look at these chapters, I think because I want to now talk about great companies. Great companies are in the title of your book and maybe to open the book a bit for the reader about which fit five companies can I learn the most when reading the book?

[00:15:18] Simon Kold: Yeah. So the book has a lot of company examples. There’s like, I don’t know how many there are, but that’s every time I mentioned something, I usually follow up with one example and kind of a counter-example and jump back and forth between contemporary and all examples.

I think Apple is probably the company that I used as an example most. Probably followed by Berkshire, but then you asked for a top five. It’s difficult for me because there are just different examples of different things. There’s an example with ASML. There’s an example with the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

There’s an example with Saudi. Yeah, I’m code. There’s an example with Standard Oil. There are examples of different companies from different times with respect to different things, so it’s difficult to say top five, but at least I had to take some Apple stuff out because people said there’s too much Apple. You use Apple as an example, too many times. So I had to turn it down a little.

[00:16:08] Tilman Versch: Maybe let’s take Berkshire and Apple. What makes them a great company?

[00:16:17] Simon Kold: Oh, OK. So I think Apple is like, I just think Apple hits many, many of the examples. So if you look at it, it would be difficult to go through all of them. But I think if we talk about passionate management, I think it hits, without going through all the determinants discussed in the book, but I would just say I think it hits many of them. It hits incentives pretty well.

They have a very good track record of capital allocation, they bought back nearly half of the shares outstanding. Also at the time when the company was a little very, very low they have– There’s a table in my book where I show all the predictions that Tim Cook has made on historical earnings calls and compare them to exposed outcomes to kind of show how you can go back and simulate having followed the company and as input to assessing the reliability of what they say today. I think Apple has multiple kinds of interesting company competitive advantages. It has switching cost multipliers.

The more Apple products you own the lists inclined you to switch. It has a brand that I think qualifies as a brand advantage, even though I’m quite sceptical of that. It has network effects. You have different kinds of network effects you have there. You have a two-sided network effect on the App Store. You also have ecosystem network effects.

I think Apple has had great reinvestment options. You know, they could expand into adjacent product categories that were not only financially lucrative but also increased the strength of the existing stuff they had. So anyway, I think that you could debate whether there have been two value extractives.

That’s maybe a drawback where you could say maybe they have the question, have they extracted too much value as a percentage of the value that they created for developers? And also I mean to what extent have they used some of their pricing power? You could have a discussion on it.

Anyway, let’s not go too much into it, but I think it should. Well, I guess it should be pretty clear to people who know a little bit about Apple. That’s also a very well-known company that it’s a great company. So I think Berkshire, I mentioned specifically with– So without going specifically into the underlying companies that Berkshire on, but I think the example where I mentioned Berkshire is in relation to internal diversification.

So when you’re concentrated on, that’s the like, I’m personally you’re very concentrated on this, right? I think it’s a plus. If you have some degree of internal diversification, you sometimes see companies that succeed in internal diversification and then you see companies that don’t succeed in internal diversification.

You have some high-efficient and some low-efficient conglomerates and I use Berkshire as an example to discuss and lift calls or some of what I view as some of the determinants of successful companies that are quite decentralised but still have a lot of internal diversification. And also I think I also mentioned it in relation to making the argument that I don’t necessarily view cyclical industries as a bad thing but it requires of course that you’re mentally prepared to act in a downturn.

For instance, Michael O’Leary of Ryanair. But I think it also Berkshire has shown to be not that, not that their businesses are necessarily cyclical or I don’t think they are, but just the mindset of being conservative through the cycle and then being aggressive in the cyclical downturn.

Identifying greatness in a company with “On the Hunt for Great Companies”

[00:20:12] Tilman Versch: Are you delivering with your book “On the Hunt for Great Companies“ a general definition of a great company, or is it more that the book gives you a big, big checklist and green list to find greatness?

[00:20:25] Simon Kold: But it’s not meant to be a checklist, Tilman. It’s not meant to be like I think if you use this as a checklist then you only end up with very few companies. So it’s not meant to be a checklist, it’s meant to be an analytical recipe for various aspects of quality, right? There’s there will be very few companies that will hit all of these criteria.

Very, very few. There will always be something where it’s weak or where you can debate it. I think what you should try to do is invert a lot. Try to think about for example, OK, so what are the competitive disadvantages that might target company might have in relation to its direct or indirect competitors? OK, so can I then use this tool, these recipes that I described that I get from Simon’s book to evaluate the advantages that the competitors might have or might comment, for example, or focus on, OK, so already based on sort of high-level pattern recognition I can see that these are the weak spots of this type of company.

So let me approach the determinants as described in this book and focus on that. I don’t think it should be like– It’s not my intention that people should be using this as a crazy make-up checklist. That’s not really the intention.

But of course, it could be used in that way. But I don’t know. I don’t think you need to follow through on everything, but it can work as a unified mental model also. So it’s not only about empirical stuff and analytical stuff. Just all of these chapters and all of these determinants.

If you kind of use them as a mental model. So not going in and doing all the stuff that I write about, but just that Forks is a great I think sort of framework for discussing overall quality as a mental model. So it can be used in that way as well.

[00:22:24] Tilman Versch: In your personal research process, how long does it take for you to identify greatness at a company? So how many hours, days, and weeks do you have to invest?

[00:22:38] Simon Kold: But I think there’s something different like I think, so the book you can– I would separate identifying and evaluating. Identifying, I don’t think it’s not perhaps necessarily that difficult to identify stuff. You can identify some of these characteristics that you think are there and you think this company might be great.

That’s not very difficult. But I think what is harder and what I what is I think justifies this book is then OK, so now I have a theory that this company is great. And that doesn’t take a lot of time to figure out. That’s basically just like pattern recognition. Now I want to test it and I think I want to, and of course, your testing doesn’t mean that you get to like I proved it, that’s not the point, right? It means can I increase or reduce my conviction based on actual facts with regard to the relevant determinants of whatever I thought made the company great.

And that I think is a little bit more difficult and can take time, but it depends on the case. So for example, if you talk about network effect, right, if it’s the type of network effect that’s sort of very local, you might have to go out and do work sort of area by area and a sample of areas just to understand some of the dynamics, but if it’s a global network effect maybe– So it kind of depends on the situation, what is required varies case by case. The point is not that you should be doing the diligence to death that is totally not the point.

Thought patterns in evaluation that can make investment decisions go wrong

[00:24:18] Tilman Versch: What can I or one get wrong when I try to identify and evaluate greatness?

[00:24:26] Simon Kold: Well, I think what you can for sure get wrong is that you see something, that just takes an example, you see something that reminds you of something, so you use kind subconsciously you use kind of an argument of analogy. This company reminds me of this. This other thing I have seen.

Therefore it’s great. It’s kind of like the visa of this or it’s kind of like the, you know what I mean? Like that, that kind of logic. You see a lot in kind of when people picture to start, they use these analogous arguments. It could also be that you rely too much on anecdotal evidence that is supportive of your own thesis.

So you kind of subconsciously, even though you don’t, you don’t know it, you have just given more weight to some evidence to support your thesis. And I think having a systematic approach to how you evaluate stuff is great, and I think that is what I tried to do with the book.

Discover the Plus Investing community 👋🏻

Hey there!

Discover my Plus community! The community is great for passionate, professional investors.

Here, you can meet investors, share ideas, and join in-person events. We also support you in starting and scaling your fund.

Popular myths

[00:26:02] Tilman Versch: Have you identified any myths or misconceptions investors have about great companies or greatness in companies?

[00:26:11] Simon Kold: One thing I think is kind of interesting, is you go to an investor event and you start discussing with people what’s a great company. I think most people will kind of agree on the same thing. Well, you know, they need to be a competitive advantage. It’s good if it’s not too capital-intensive.

It’s good if it’s not too cyclical. It needs to have capable management. It needs to have a high return on invested capital and so on and so on and so on. But then when you look at their portfolios, they are in they are always in totally different positions and one guy he’s like how can you?

So I think people give weight to different things. Like for example, I’m personally probably a little bit more interested in emerging quality. So companies that are not obvious quality, they’re not established quality where it’s kind of so obvious to everybody that they’re quality. It’s more like at the intersection of quality and emerging quality.

That’s not about the book, that’s just my personal sort of what I like to have to depend on qualitative work to be able to determine it and not just be able to rely on it. What is extremely obvious and just heuristics like return invested capital or margin? I like to go a little bit deeper, but that’s just a personal preference. I’m not saying that’s better or worse. Did lose the question a little bit there?

[00:27:34] Tilman Versch: No, it’s about the myths and misconceptions. And you shared a bit.

[00:27:38] Simon Kold: OK, so yeah. I think that’s quite interesting, right? So people kind of agree on what is a good company, but then yet they’re ending up with totally different companies. So they don’t agree, right? So then in their actual investment process, there are all kinds of individual preferences for what makes a company, attractive from an investing perspective or not. So they don’t agree.

They don’t agree, so there must be someone who knows who’s right. Like I’m not saying misconceptions but diverging views on what’s a great company. And I think, for example, the longest chapter in the book “On the Hunt for Great Companies” is about network effects probably because that’s kind of where I have most personal experience.

And I just see a lot of people talking about network effects and when you hear these investing podcasts you see some write-ups or something. You see people sort of casually just mentioning it as if it was kind of just like a binary thing like network effect yes or no. OK, check. It’s kind of like, OK, wait. Hey, wait a minute. There are all these determinants that make the network effect intense.

And what makes it durable is that you can decompose it multiple times and you can analyse empirically the determinants of that. It isn’t just as simple as a kind of yes or no checkbox. Check and move on to self-verification of my pre-existing investment hypothesis. It’s not that simple. That said, though, I think there might be some people who will criticise my book for saying, well, aren’t as some investors who are so good at pattern recognition that they can kind of apriori by their own thinking kind of identify and you know I think there is.

There are probably people like that, but I bet you it’s not you. I bet you it’s not you and it’s not me. So I think for most people, except for maybe some kind of super genius like Warren Buffett. I think most people are well served by doing a lot of this empirical work.

The role of passion in “On the Hunt for Great Companies”

[00:29:47] Tilman Versch: You have a whole section about passion in your book “On the Hunt for Great Companies“. Why is passion important for great companies?

[00:29:54] Simon Kold: So I think it depends a lot on your investment hypothesis, sort of on your investment time horizon. If your time horizon is one to three years, then I don’t think passion matters at all really. But if you’re like me, if you’re more long-term. I don’t have really any proof to back this up and it’s based a little bit on, you could say anecdotal evidence, but if you look at the really maybe back, maybe I can inject something, sorry if I’m answering it.

Is it O it will be a little bit longer answer? So I don’t know if people listening to this, if they’re familiar with the Economist Hendrick Bessembinder, who made some studies on the statistical distribution of shareholder wealth creation. Maybe you can link to maybe some of his articles, but he basically found that if you look at from 1926 to today.

If you kind of just bought the entire market and every time there was a new company, you, you bought it and you hold, you hold it, you hold everything. So it’s kind of a permanent buy and hold of the entire market. And then you look at this time over this sort of since 1926. How was the statistical distribution of wealth creation? You find that 60% of all stocks, underperformed tea built during their lifetime and the top 40, not top 40%, but top 40 stocks, they generated more than I think it was more than 40 or 50% of the entire shell equation.

If you then look at some of these companies. You look at some of these sort of 1000 baggers. What kind of had did they have in common? I think a lot of them had like really, really passionate management. They had really, really passion management and of course, there’s a lot of survivorship bias.

And I again, you can criticise me for making the argument and so on, but I just think if you– So this is my belief, I cannot prove it. But my belief is that if you want to aim for the kind of power law distributed like you know the stock market is a power law distributed if you’re a buy-and-hold investor similar to venture investing. And you’re like, OK, so how can I increase the chances of hitting like a really crazy multi-bagger?

I just postulate that I think passionate management is going to increase the likelihood of that. So that’s why I focus a lot on it. But of course, if you have a different time, right, I think it makes no sense to go through all this work of evaluating passion. It’s kind of quite time-consuming if you have to follow all these recipes. I think if you have a shorter time horizon it’s a total waste of time because it’s not going to matter.

But I think you know decisions kind of compound and accumulate. Kind of like the same way an investment can accumulate. I think decision on a decision on a decision, on decision, on decision accumulates and if those people are really, really passionate, they are really, really perseverant. They really drive for the long term. They love what they do. They would do it even without the money and so on and so on and so on.

The people below them, stay in the company. They have high retention, they communicate in a really crazy offensive way and so on and so on and so on all of these determinants. Then I think you’re not sure, but you’re more likely to hit the really long-term winners. And I think if you compare yourself to an index fund, an index fund is always exposed to the next thousand bigger. It’s always exposed to the next thousand baggers, but you’re not like in my concentrated portfolio, I’m probably not, right? So I have a competitive disadvantage there. I am not exposed to the next thousand bags and I think at least by focusing on passionate people, maybe I may go a little bit of that.

Things to look for in a company

[00:33:30] Tilman Versch: So you mentioned the sectional passion, maybe as a small teaser to the book, what else is important to spot great companies aside from passion?

[00:33:42] Simon Kold: But I think, well, I think passion is maybe so some of the other things on people is that I have a chapter on is long-term incentives, capital allocation and reliability. But I think especially numbers two and three are probably already very well described and obvious to people.

But I think the reliability of communication is also maybe something that people don’t think about to the same extent as me or some people do, others may not, but I focus a lot on it. So in my analytical process, I kind of like to simulate having followed the company for a long time. So I’d like to go through and sort of chronologically read or listen to earnings calls and do whatever they have said in interviews and what they have written in the annual report and in shareholders and so on.

And I think this is a great exercise to do, especially if you do it in a compressed time frame like over one or two or three or four days. There are so many interesting by-products that come out of this analysis.

I know it sounds like if you haven’t tried it may sound silly, but just try to do it once, and you’ll see it. First of all, you get a pretty good idea about sort of the predictions they made compared with the ex-post outcomes.

But you also get a very good chronological understanding of stuff instead of just sort of a static view of today. And you forget a surprisingly good understanding of the business also sometimes. So I think it has some interesting side effects in addition to just evaluating the reliability of the firm because the justification for doing this is when you make an investment in a company today, I’m talking about public and private like my book is not limited to public companies, but so when you make an investment today in a company, how much of the information you’re relying on does really originate from the current management?

Well, one thing you might have had some direct interactions with them. You might have not, so you might have read what they have said and so on. But then if you rely on maybe some sell-side stuff that also originates from the management probably if you rely on some kind of industry experts, maybe that also originates a little bit there.

Their opinion is also affected by what the management says and so on and so on and so on. No matter which way you go, you’re going to end up relying on information that originates from them in how you build your investment thesis. Well then, it’s pretty important, I think, to have an idea about how reliable has that been in the past, but of course, just because it has been reliable doesn’t prove that it will be true but I mean it’s just an important input.

No matter which way you go, you’re going to end up relying on information that originates from them in how you build your investment thesis. Well then, it’s pretty important, I think, to have an idea about how reliable has that been in the past, but of course, just because it has been reliable doesn’t prove that it will be true but I mean it’s just an important input.

So what else? I think also something that maybe it’s not so much described, but I also already mentioned it before as the stuff with competitive advantages, I see a lot of people who always talk about it, if you hear like investment podcasts, investment books, they always talk about. So what’s the competitive advantage?

So all these companies you hear about have a competitive advantage, but then you never hear about some companies having a competitive disadvantage. So that’s like, that’s weird, right? So there’s something wrong, sort of statistically. If all these companies on these podcasts, whatever, have a competitive advantage, then there must be like 10 times as many companies with competitive disadvantages. Why are they never described on the podcast and so on, right? It doesn’t make sense. So all companies have some form of competitive disadvantage.

So what’s the competitive advantage? So all these companies you hear about, have a competitive advantage, but then you never hear about some companies having a competitive disadvantage. So that’s like, that’s weird, right? So there’s something wrong, sort of statistically. If all these companies on these podcasts, whatever, have a competitive advantage, then there must be like 10 times as many companies with competitive disadvantages.

Seemingly, I don’t know why I never hear about people talking about competitive disadvantages. There are people who always talk about competitive advantages. I have some stuff in the book about that. I actually had a specific chapter that I had to delete because I thought it got. I got this sort of middle part with it, got very technical and I didn’t want to lose people because I think part three of the book is the best. So I didn’t want to have people sort of drop off because it got a little bit too technical, but I still think you can just invert and justice use these frameworks to evaluate disadvantages as well. And then yeah, I don’t want to go through all the chapters.

How did writing “On the Hunt for Great Companies” change Simon Kold?

[00:38:00] Tilman Versch: It’s fine. You teased a lot and people can read the book via the link below. They also can buy it, and we also link the best and binder studies so people can also have a look at them. For the end of the interview, I want to look at you and how your transformation is done with the book. So how did writing the book change you?

[00:38:26] Simon Kold: Well, I think we can talk about two dimensions of change. So I think for me it was very frightening to start adding the humor to it. Like it was a mental journey. So I had just for context in, in about October 2023 I had written the first draught of the book. I had the whole full book no jokes, no humour. A little bit of a sort of subconscious and elitist here. And I hadn’t thought about it.

One guy he mentioned to me, he’s a professor at the Copenhagen Business School. He mentioned it to me. This book is so dry I don’t recognise your personality. I started adding a little bit to it and it felt sort of it felt really weird. Can I put this out there? It would be so embarrassing. I have all these professional investors looking at this fool with these silly jokes. And then the next reviewer who read it liked it.

So like I add a little bit more and this journey and then at some point I just kind of got over the hill and I was like, OK, screw it. Screw it. I’ll just be like 100% myself and I won’t care what people think and it was great because I had this secret dream of writing also kind of a comedy book and comedy novel or something.

So I kind of just married those two ideas in “On the Hunt for Great Companies”. And I think that was, like, beautiful. And it gave me, like, so much satisfaction. So that’s the one answer. But I also think, you internalised, this is something I probably already knew, but I know it much more now by writing down something you really internalise something.

So what’s the competitive advantage? So all these companies you hear about, have a competitive advantage, but then you never hear about some companies having a competitive disadvantage. So that’s like, that’s weird, right? So there’s something wrong, sort of statistically. If all these companies on these podcasts, whatever, have a competitive advantage, then there must be like 10 times as many companies with competitive disadvantages.

So, by writing down this book I had this framework already, I knew exactly the chapters, and how they were going to be structured when I started writing. But I just really internalised in a totally different way in respect to my own research and what I discovered is now when I do research, I really like to write these crazy kinds of like very draught kind of It’s not a write-up, but it’s like I take these structured notes.

I don’t even attempt to make it nice. I don’t want anybody to ever read them, but I only write them intending to internalising information so that it sticks in my head more. And I discovered that through writing the book also. I think that was and probably everybody who wrote a book, probably. They discovered the same I presume, but it was something that was quite interesting to discover and so I have for sure internalised this framework much more than I had before. Before I wrote the book.

Follow us

On writing “On the Hunt for Great Companies”

[00:40:59] Tilman Versch: Would you recommend other investors to also write a book, like “On the Hunt for Great Companies“?

[00:41:04] Simon Kold: Yes, but I would say so. So if you look at my personal journey, I started writing the book in January of 2023. I quit my job in the holdings and had my last day in September and I thought I had written most of the book and completed most of the book, but I totally underestimated myself.

So I was quite lucky that when I wanted to start my own because I also started my own investment firm, I had to wait quite a long time for the regulatory license and that turned out to be quite lucky for me because then I had more time to make the book really, really good. But I also just discovered how big a distraction and how much time, how much time it took from having written that first draft to editing it over and over again as I went through every single sentence and how big a distraction that can be.

So if you like to run a fund or something, and you run a write a book. I mean, I will probably not write a book again, unless it’s kind of like some kind of natural byproduct of the stuff that I’m already writing that I can publish in some form or the other like it’s very time-consuming, but I think it was a great experience, but it kind of depends if you can justify the distraction, it’s going to be because it’s probably going to be a Like it to me at least, it felt like over the window like a big distraction compared to the fact that I was also going to start an investment firm, but I had underestimated how long time it would take from writing the first draught to finishing it totally.

Closing thoughts & recommendation

[00:42:36] Tilman Versch: It’s a normal mistake you make when you start something. It always takes way longer. It is more painful. So at the end of our interview, I always want to give my guests the chance to add anything we haven’t discussed. So is there anything you want to add?

[00:42:38] Simon Kold: Yeah, maybe I would like to also recommend a few other books, actually. So if you kind of criticize my book for being kind of too checklists-ty, I think it would be interesting for you to read the book called The Checklist Manifesto.

I think you will have a different view on sort of the process of checklists. There’s another book, it’s not recommended in my book, but I think it’s quite useful. It’s the book called Factfulness by Hans Rosling. They talk a lot about this thing called the gap instinct and I think this aligns very well with the kind of thinking that I saturate so much in the book, in my book. But these are not investing books.

These are just like other kinds of books, but I think they have some interesting aspects both that I think parallel my book in some way that I think they would complement my book in a good I mean I’m not trying to compare myself to these books they are like crazy bestsellers, right? But I think that they would complement my book in an interesting way. I think if you disagree with me after reading my book, you should maybe read those two books.

Goodbye

[00:44:06] Tilman Versch: Then thank you very much for this edition. I will link them below for people so that they can find them to buy. And Simon, thank you very much for our interview and for sharing your insights with us.

[00:44:18] Simon Kold: Thank you so much, Tilman.

[00:44:20] Tilman Versch: And bye-bye to the audience. Bye-bye. I really hope you enjoyed this conversation. If you did, please leave a like in the comment and for sure subscribe to my channel. Traditionally, I want to close this conversation with the disclaimer, so here you can find the disclaimer. It says, and please do your own work. This is no recommendation. What we are doing here is just a qualified talk that helps you. But it’s no recommendation. Please always do your own work. Thank you and hope to see you in the next episode. Bye-bye.

Good Investing’s disclaimer

Please be always aware that this content is no advice and no recommendation and make sure to read our disclaimer: